It’s people who shape our research – here’s how

Research is our bread and butter at IGHI. It lets us explore problems, ask questions, test ideas, make mistakes and learn from them. And after all that, find the right solutions to the issues we’re trying to address in healthcare.

None of this would be possible without people. But not only the brilliant researchers who are the driving force behind our progress. The patients, carers, public and healthcare professionals who devote their time to get involved and be part of our research play an invaluable role in what we do, too. It is through their knowledge and lived experience that we know we’re asking the right questions and chasing the right solutions.

This International Clinical Trials Day, we want to highlight why being involved in research is vital to make progress in healthcare, and shine a light on some of the people who are doing just that.

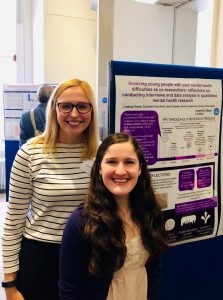

Caroline’s story

“I was studying social sciences in London when I first got involved in research at IGHI. I’d been wanting to gain some experience in carrying out research, beyond filling out forms and surveys. I’m really interested in mental health and try to keep my finger on the pulse with what’s out there. So when this opportunity landed in my inbox, looking for young people with lived experience of mental health difficulties to take part in a project as co-researchers, it immediately struck my interest.

“The study was exploring the use of technology to detect deteriorating mental health in young people. We were involved in every stage of the project, helping to shape the work in a way that was meaningful. Sometimes it can feel like involvement is a bit of a tokenistic gesture to fulfil the criteria of a grant, but Lindsay and Anna, the research lead and involvement manager, never gave me that impression. By involving us, they wanted to make sure that the research was asking the right questions, and that it was relevant and of interest to the young people she’s seeking to help through her work.

“After helping to guide the direction of the research, we were trained to carry out interviews with young people with mental health difficulties, and then to code the transcripts and help analyse them. We even attended conferences and shared our findings at various events, so we really got to take part from start to finish. That meant I could really see the impact of the work and how everything fits together.

“It also really impacted me; knowing you’ve played a part in something that will likely affect others going through what you’ve been through is a really rewarding experience. And off the back of this project, I’ve actually started computer coding and will be starting a master’s in computer science.

“Before I joined this research project, I wasn’t really sure of the difference I could make. But I was so wrong! I worried my contributions would be the obvious thing to say, but I realised having that lived experience really does add another perspective that’s needed in research. I would definitely do it again and encourage others to do so – you really can make a difference.”

Anna’s story

“I’m the Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement (PPIE) Lead at IGHI. My role is to support the meaningful involvement of patients, carers and the public in research.

“It’s great to see how people like Caroline have not only impacted the research, but also gained from the experience, including learning new skills and growing in confidence. That’s why it’s so important that engagement and involvement in research continues despite the current crisis. Although COVID-19 has meant that we’ve had to change the way that we do this, we’re learning a lot and finding that involving people virtually can still be a really valuable and successful process.

“For online meetings, for example, we use ice breakers like “What’s your favourite lockdown TV show or book?” to help remove hierarchy and find some common ground, before we get the group to work on a task together. We’re using live captioning on our online platforms so people can read what is being said as well as listen, which has not only been useful for those with hearing loss, but also helps visual learners to reflect more on what is being said.

“Due to not being in person to read body language or take people outside for a chat, there is a greater need to ensure appropriate safeguarding. For example, we offer to chat to people individually before the meeting and introduce them to the online platform, so they will be familiar with at least one person. For sensitive topics or with vulnerable people, we have clinicians either in the meeting or on-call (to support people, as needed). We also ask individuals to provide a friend/family member’s contact details and signpost to appropriate support services (e.g. SHOUT crisis textline).

“We’re also thinking about ways to involve seldom heard groups during COVID-19, for example by providing dongles, as people might not have access to WiFi or unlimited data. We recognise not everyone wants to, or is able to, interact online. We want to build on existing community groups (e.g. through a buddy scheme or phoning rotas), but we also understand people might have more immediate needs to tend to.

“My colleagues and I are very grateful to the amazing, altruistic people who, although some of their situations might not improve, want to be involved in research to help others. We’re glad to hear people enjoy the experience of giving something back to the NHS. I enjoy seeing researchers, clinicians and public members learning from each other and, particularly now, learning together during this pandemic.”

By Dr Justine Alford, Communications Manager, IGHI

By Dr Justine Alford, Communications Manager, IGHI