Quaisr: Digital twins for the machine-learning age

Omar Matar, CEO Quaisr, Vice Dean of Engineering and Professor of Multiphase Fluid Dynamics at Imperial College London.

Digital twins have been around for some time (in fact, the term ‘Digital Twin’ was coined in 2003 by Michael Grieves of Florida Institute of Technology) and are used in a variety of sectors, from manufacturing to energy to consumer goods. One way to define a digital twin, inspired by Arup, is a combination of computational models and a real-world system capable of monitoring, controlling, and optimising its functionality, of developing capacities for autonomy, and of learning from and reasoning about its environment through data and feedback, both simulated and real.

The ongoing trend towards digitalisation of just about every sector is driving massive acceleration in digital-twin adoption as new data streams become available to organisations. The digital-twin market is reportedly experiencing 100% growth year-on-year with some projecting that it will reach $48 billion in 2026, from just $3 billion in 2020.

Despite this growth, the full potential of digital twins has yet to be realised. With colleagues from Imperial College London and the Alan Turing Institute, I co-founded Quaisr to bring digital twins into the machine-learning age, allowing enhanced capabilities with applications spanning environmental monitoring to improving infrastructure resilience.

But what exactly are digital twins? You can think of a digital twin as a digital replica of a physical asset. An asset is instrumented with a variety of sensors which collect and feed information back to the individual or system controlling the asset, who can then action interventions based on this information.

In the most basic sense, digital twins work to integrate various sources of digital information about the asset and its environment to allow more efficient and predicative modifications and iterations on the physical world.

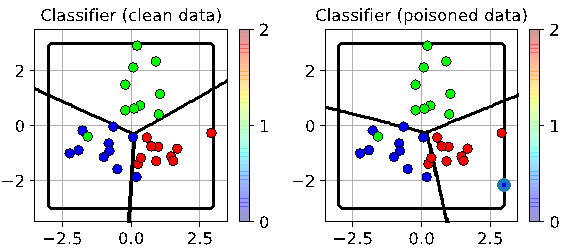

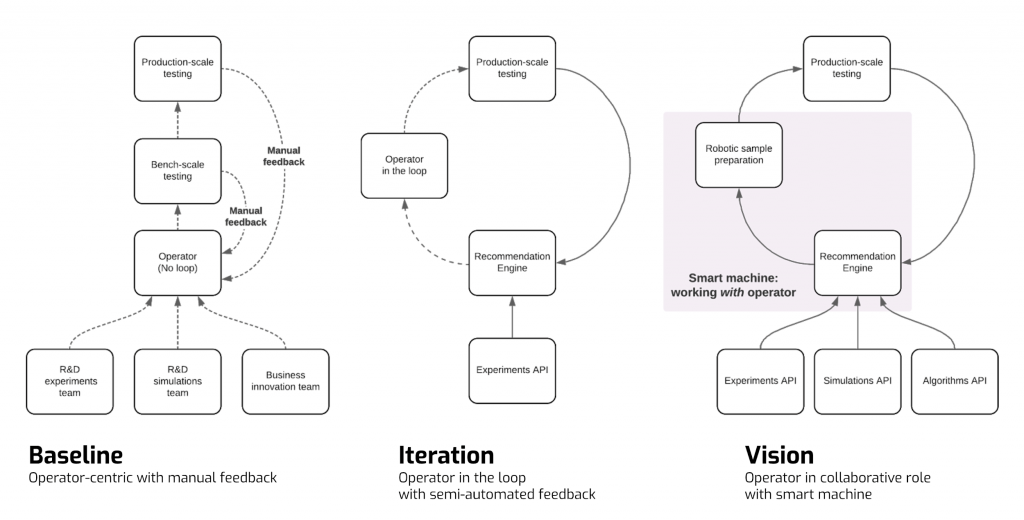

If you think about the baseline of how this happens, the data-integration and iteration journey revolve around the operator. For example, as shown graphically in the ‘Baseline’ image below, R&D teams that run experiments, simulations or other innovation projects feed data to a human operator, who then runs small-scale tests followed by production or pilot-scale testing. At each of these two stages (bench, production/pilot), there is manual feedback of asset data back to the operator to allow for iterative improvements.

Using existing technology, we can go one step beyond this as shown in the ‘Iteration’ image. Here, the operator stays in the loop but with a semi-automated feedback process. For example, you might have experiments automatically feeding data into a digital recommendation engine at one end, and the production scale tests doing the same at the other end, but with an operator in between deciding on whether or not to act on the intelligence provided.

But now imagine a situation where you have an operator interacting and collaborating with a smart machine, as shown in the ‘Vision’ image. This is what we are really driving towards with our approach to digital twins.

Here you have information from experiments, simulations and algorithms driving the recommendation engine, together with the information coming back from the production testing. Between these two sources of information in the loop you have a robotic operator or smart machine actioning the suggestions, collaborating closely with the human operator. This opens up many new opportunities in not just optimising physical assets but also understanding how they might behave in a given situation. If basic IoT streams allow you to understand the health of the asset, the ‘what now’, and the addition of machine learning unlocks future projections through ‘what next’ questions, Quaisr digital twins enable the ‘what if?’ type question. For example, you might want to know how your asset will behave if it is pushed outside of its comfort zone into a completely new operating space: to understand if it will be safe, secure and resilient.

The types of challenge that our digital twin components can address are broad; from helping to solve challenges such as environmental contamination detection, to production-line decision automation, to optimisation of offshore wind farm locations. We have projects completed, in progress or starting soon with major companies at the operational level.

Quaisr provides modular components for building digital twins, backed by a managed service. We help customers to create their own digital twins using in-house domain knowledge, reducing the problems of adapting and commissioning generic commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) alternatives. Quaisr components empower citizen developers to build production tooling using internal company data streams and existing cloud-provider resources.

Our approach accelerates the journey to digitalisation by providing insight for design and prototyping, by bridging the gap between data and actionable intelligence to empower decision making. Our approach also unlocks collaboration via a cross-team digitalisation standard. Importantly we prioritise interoperability with existing technologies in a company’s ecosystem, allowing the integration of often siloed legacy data with newer data streams and machine learning.

Digital twinning is a developing field, and so whilst there are several existing companies with capabilities in one or more of the underlying aspects such as data streaming or simulation, Quaisr is unique in taking a digital-twin-first approach, combining all of the elements to make the infrastructure for creating digital-twins.

With the rapid speed at which global digitalisation is taking place, and with the rapid improvements and deployment of machine learning and simulation, the next phase of bringing these factors together to realise increased capabilities and efficiencies will depend on digital twins. Quaisr is at the forefront of this revolution.

For more information on how we work with companies, please get in touch at omar@quaisr.io.