A post by Professor Chris Hankin, Director ISST. This blog originally appeared on publictechnology.net published 19.06.2017.

With the cyber threat shifting its focus to sabotage rather than data theft, many of the defences deployed by public sector organisations will have to be adapted for the new world.

Information security policies are commonly guided by the CIA triad of confidentiality, integrity and availability. Many of the big security stories in the media relate to confidentiality, where data theft, for example, affects both individuals (eg. personal banking data) but also has a huge economic impact as a result of industrial espionage.

Integrity, or rather its loss, is most evident in the hijacking of websites by “hacktivists” seeking to deface content or replace it with political messages, but can also be associated with data, such as environmental monitoring, stock market trading or consumer price indices. Availability is often compromised by denial of service attacks as well as natural disasters, while recent high-profile ransomware incidents, when individuals and corporations are denied access to their data while a ransom is extorted, can also be counted in this category.

50 billion connected devices

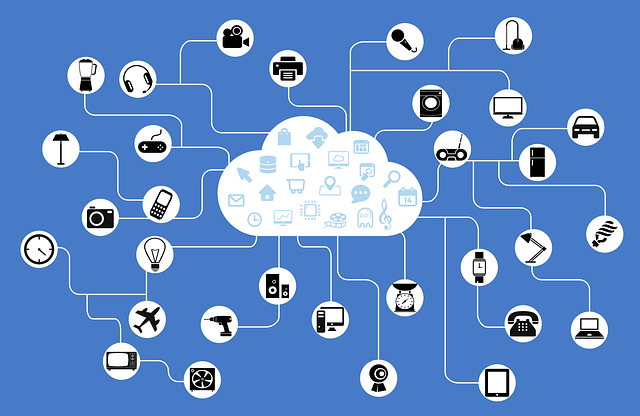

The CIA triad addresses the security of information technology systems – our desktop computers, laptops, tablets and phones. Whilst these may represent the majority of the devices connected to the internet today, this won’t be the case in the future: there are currently around 15bn connected devices, set to rise by some estimates to more than 50bn by 2020.

This huge growth is fueled by the emergence of the Internet of Things in which connected devices control many aspects of our physical environment from home and leisure, autonomous vehicles through to city infrastructure. This move into the cyber-physical domain has already been presaged by the convergence of IT with the control systems built into our critical infrastructure and industrial processes. These systems were historically separated in both design and implementation, but economic necessity has driven them together. For example, the millions of lines of code which control a modern automobile has little separation between engine management and the car’s entertainment system.

New types of cyber attack

We have seen new types of cyber attack that are aimed at sabotage rather than data theft – such as the December 2015 attack on the Ukrainian power distribution network, commonly attributed to Russian involvement. The IoT hasn’t been immune either, with the emergence in late 2016 of the Mirai malware which targets machines running Linux and was used in the distributed denial of service attack (where multiple compromised systems, which are often infected, are used to target a single system) on the internet company Dyn. That attack was mounted through a network of Mirai-infected printers, domestic gateways, baby monitors and cameras (note, again, the lack of separation between consumer electronics and corporate and operational systems).

Many of the cyber defences deployed today will have to be adapted for this new world. It is unlikely that individual IoT devices (CCTV cameras, toasters) will have the computational power to run anti-malware software, and both safety and access considerations may militate against regular software updates. The increasing emphasis towards security-by-default (ensuring systems are set to the most secure settings) may help, but there is also likely to be a greater reliance on intrusion detection and prevention at the system level and a greater role for network monitoring.

These kinds of tools were traditionally based on recognising fixed patterns that are indicative of illegitimate behaviour, but there has been a recent trend towards tools based on anomaly detection. The latter tools use the artificial intelligence technique of machine learning to identify threats. Such techniques suffer from the so-called false positive problem – they may identify anomalies where none exist – but they are improving. Another problem is that it is sometimes difficult for the human monitor to understand why an ML algorithm has arrived at a particular decision. This is an important area for current research and we can expect to see rapid progress in this area. Since many artificial intelligence applications use machine learning, such advances are likely to have ramifications beyond the confines of cyber security.

The end of passwords

Another major area for change is in authentication. In the IT sector there is already the realisation that approaches based on strong passwords are not sustainable. GCHQ has produced more nuanced advice about passwords that recommends a number of simplifications. In future it is likely that other means of authentication will take on a more important and widespread role. Modern smartphones are already equipped with accelerometers (useful for gait recognition), fingerprint readers, microphones (voice recognition) and front-facing cameras (face recognition, retinal scan). A group of British universities recently developed a notion of cyber-metrics which supports authentication based on human-computer interaction, including measuring typing speed, pressure and interactions with a touch screen.

“In the IT sector there is already the realisation that approaches based on strong passwords are not sustainable”

It is clear the cyber world is changing and we can expect to see much more about cyber physical systems in the future. There are some exciting developments in the fields of artificial intelligence, particularly machine learning, and biometrics that will help to make us more secure. Expect to see rapid developments in the next few years as safety and security try to keep pace with increased user demands and technological capability.