Testing youtube videos

Here is a youtube video embedded in the page:

And some text to follow.

Sdad

asd

asdsadasdas

Here is a youtube video embedded in the page:

And some text to follow.

Sdad

asd

asdsadasdas

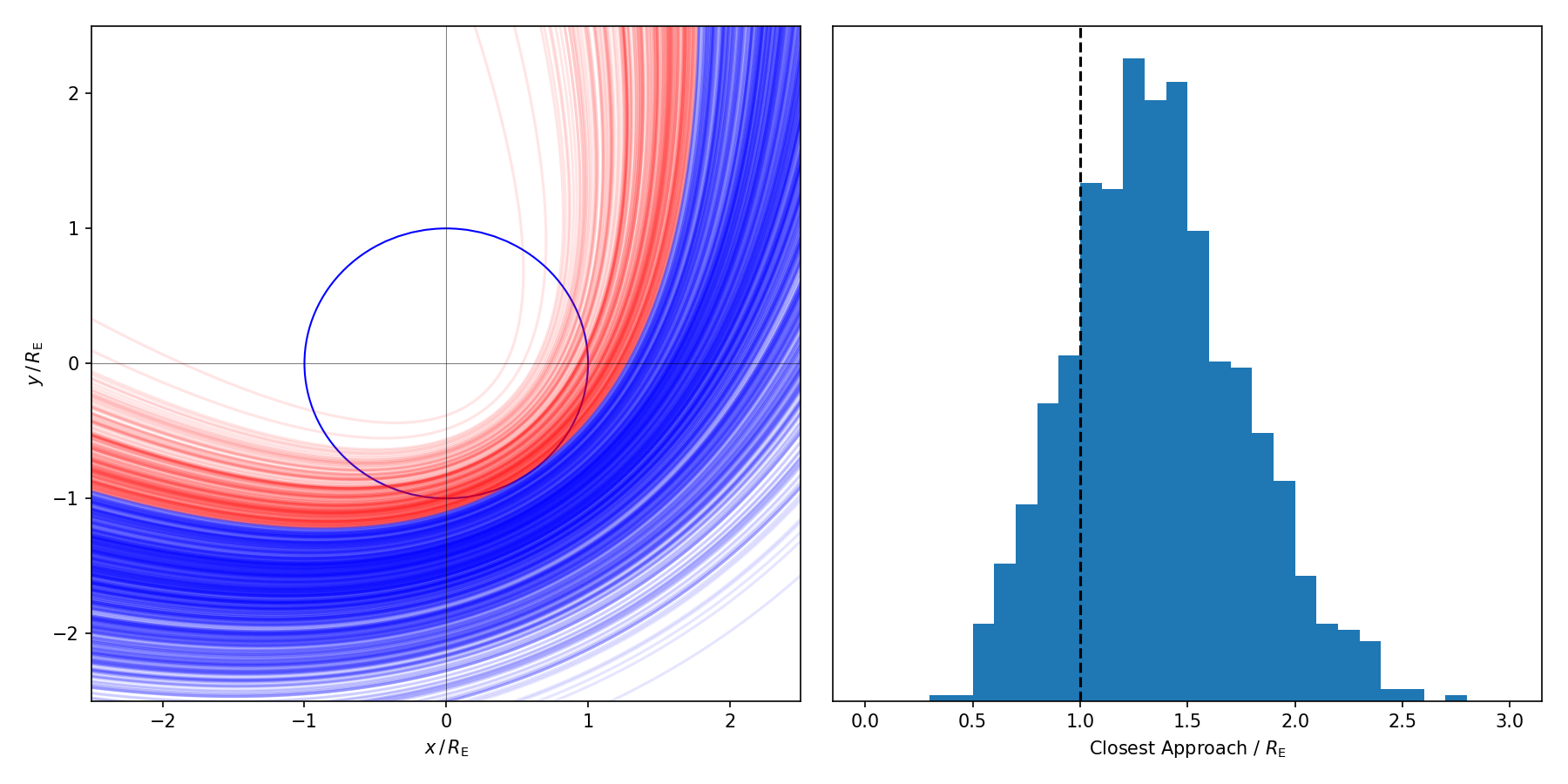

Plasma physics PhD student Lloyd James teamed up with Dr Yasmin Andrew to run a postgraduate student project developing Python-based simulation problems rooted in the undergraduate physics curriculum. In this blog post the duo tell us more about the project.

By Dr Yasmin Andrew and Lloyd James

In 2019 we recognised that many physics students’ second year laboratory courses, final year research projects, and summer UROP projects would directly benefit from more opportunities to develop their coding skills. Students start their undergraduate physics studies with a very wide range of abilities, experiences and backgrounds in coding. Most students have no programming experience at the beginning of their first year. Python, and coding more generally, is not only an increasingly relied-upon tool in physics research, but also a hugely transferrable skill that opens up doors to other exciting fields such as tech and data science. This was the motivation behind the PyProblems project.

In developing questions directly linked to students’ ongoing undergraduate studies, the ‘PyProblems’ initiative would allow them to practice using mathematical and computational skills to solve conceptual and quantitative physics problems. The result has been a stand-alone bank of Python-based physics questions and Jupyter-notebook solutions that students access voluntarily and which helps improve and maintain their coding proficiency and confidence.

Physics PhD students were recruited to work directly with the course and module leaders to develop the problems and solutions, with the only brief being to be both rigorous and creative in the original question design and construction. The project benefitted from these students’ subject knowledge and Python experience, and a valuable outcome for the students was the pedagogical opportunity to develop teaching and learning resources early on in their academic career. The first set of first year problems and solutions was initially released in December 2019 while the second set for some Year 2 and 3 physics courses was completed for the start of the 2020/21 academic year.

The rollout of the project was supported by a group of physics PhD and final year MSci students who set up a series of hour-long Python Helpdesks in the Blackett Computer Suite on a voluntary basis. The purpose of these helpdesks was to directly support students in working through the PyProblems questions, and also provide help for any other coding questions they might have. This student-led initiative was so successful it was adopted by the Department of Physics as part of the ongoing undergraduate student support over the 2020/21 academic year, switching to an online Teams format.

This is an exciting time for the PyProblems initiative, which has now reached the stage of planning for future extension of the resources to the Year 3 and 4 modules and possible collaborations with other Imperial departments, as well as external higher education institutions.

It’s an excellent example of a postgraduate student-led collaboration with staff, which showcases how PhD students can directly contribute to the development of high-quality teaching and learning resources with their valuable subject and technical knowledge.

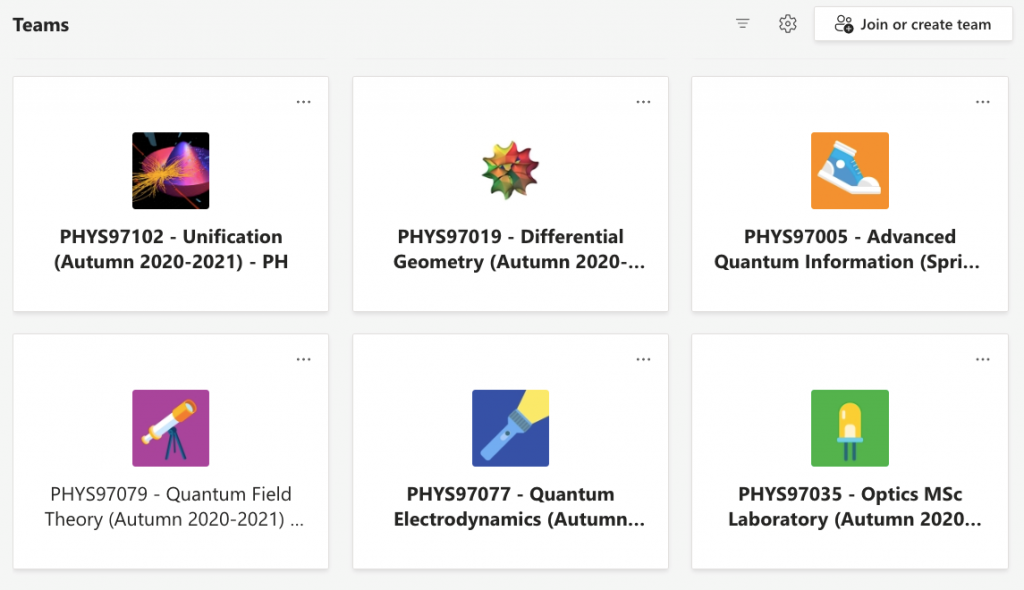

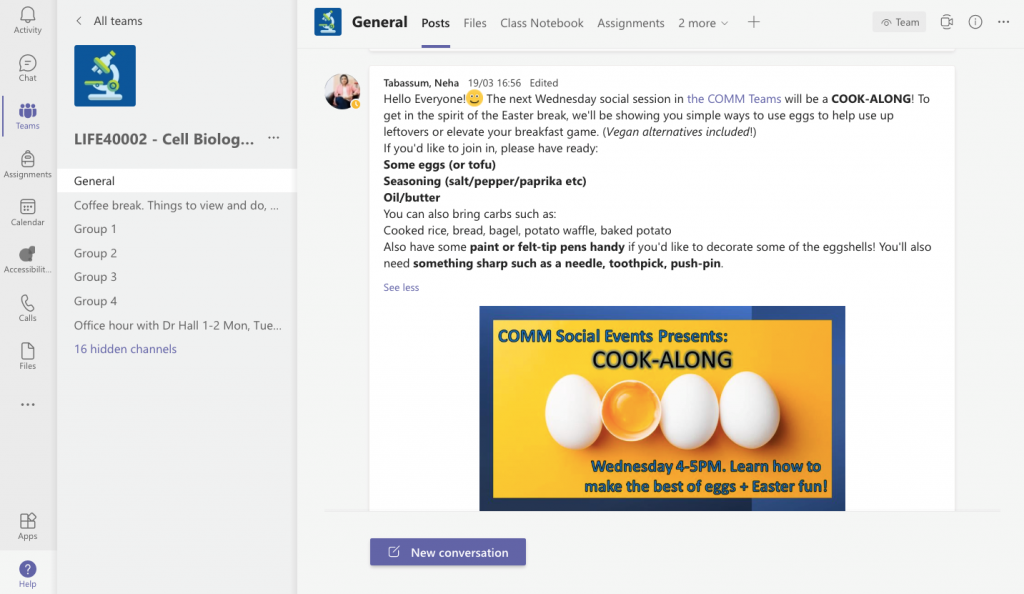

In this blog post Helen Walkey, Education Insight and Evaluation Analyst from the FoNS Ed Tech team, reflects on how Microsoft Teams has not only become an integral part of staff collaboration, but also the ways in which it has underpinned Imperial’s teaching activities over the past year.

By Helen Walkey

With the shift to multi-modal delivery of teaching and learning, interactions that would have taken place in lecture theatres, tutorial rooms and physical groupwork spaces needed to be recreated online. Into the spotlight came MS Teams, used previously in College as a tool for collaboration, but new to the suite of supported tools for teaching and learning.

Students responded positively to its introduction for summer term teaching, during the first lockdown, frequently listing it as one of the tools that worked best to support different learning activities.

For the academic year 2020-2021, the ICT Student Lifecycle Product Team led a successful cross-College project to create standardised MS Teams sites for teaching and learning for each taught module. The aim was to support the delivery of synchronous and interactive sessions designed by teaching staff, and to provide a consistent experience for students.

ICT, EdTech teams, the Central Timetabling Support Office and Curriculum Data Management Team worked effectively to define requirements, create and test an automated process for generating standardised MS Teams sites for modules, with membership fed from the student information system, Banner. Links were made with the timetabling software, Celcat and the virtual learning environment, Blackboard, to provide a joined-up experience for students. Moira Sarsfield and I, from the FoNS EdTech team, represented the Faculty on the project team. Additional manual tailoring requested by departments was done by EdTech team staff and Graduate Teaching Assistants. Departmental Education Office teams helped to troubleshoot issues with data from Banner. The ICT team produced and published extensive help material describing how MS Teams can be used to support remote teaching and learning, based on input from Faculty EdTech and teaching staff.

The automated Teams set-up process has been used by all departments in the Faculty of Natural Sciences and has had a huge impact on both staff and students, who have used Teams for many different learning activities, for example: live Q&A sessions covering taught content, tutorials, problem classes, seminars, team-based learning sessions and even online poster sessions.

Euan Doidge, Senior Teaching Fellow, Department of Chemistry reported the benefits for staff: “The process developed was a great time-saver at a busy time of the academic year. By instantly generating Teams and applying our template across our 30+ modules we avoided the manual and repetitive creation of individual Teams/channels and potential errors when doing this. The auto-enrolment of specific students and staff as Team members reassured us that people would have the correct access immediately avoiding many careful user additions. The Teams were easily maintained centrally, giving us an overview of all remote/synchronous teaching, and allowed individual modules to focus on teaching knowing everything was already set up properly. The consistent format of channels and Breakout Rooms across all module Teams made training of staff and students easy and allowed everyone to quickly get on with teaching and learning instead of navigating or creating several unique Teams”.

This was echoed by Jerzy Snelling van Buren, Undergraduate Administrator, Department of Life Sciences, who said: “Having processes to automatically generate Teams sites and Blackboard courses for modules then populate them with the relevant student lists from Banner has been really useful. It’s been hassle free and has saved us time”.

From a student perspective, when asked about activities they had found most interesting, one reported: “The Q&A sessions [in Teams] have been helpful and in fact likely increased lecturer/student contact compared to a normal term – it’s also a good way to see and interact with the other students on the course.”

From this and other student feedback, it is clear that students have really missed social interactions during the pandemic and another positive outcome of using Teams for teaching and learning is that it is playing an important part in keeping them connected.

Five early-career researchers from Imperial recently presented their research at the annual STEM for Britain parliamentary poster competition.

Five early-career researchers from Imperial recently presented their research at the annual STEM for Britain parliamentary poster competition.

Ben Lewis, who works in the Vilar and Kuimova research groups in the Department of Chemistry, and the Vannier group at the MRC London Institute of Medical Sciences, won the Gold Award in the Chemistry category for his research: ‘G-Quadruplexes: Unravelling the next knot in the DNA story’.

In this blog post he reflects on what it was like to present his work to MPs and Lords at the Palace of Westminster.

By Ben Lewis

As PhD students, we often get opportunities to present our work to other researchers – whether within Imperial or beyond. It is very unusual, though, for us to have the chance to present to MPs and Lords. That’s one of the unique features of the STEM for Britain poster competition, held annually for early-career researchers by the Parliamentary and Scientific committee.

In normal years, the event takes place at the Palace of Westminster itself and brings together a range of scientists from academia and industry with parliamentarians. Sadly, this year an in-person event was not an option – but it was particularly amazing that the competition could still happen in spite of the ongoing pandemic. We still got to engage with one another – just through Zoom and the screens of our laptops.

This competition also brings together all fields of science, with categories for Chemistry, Biology, Physics, Engineering and Mathematics – a great opportunity to hear about a range of work, which isn’t always the case in many of our field-segregated conferences and seminars. Reading posters on topics from tackling traumatic injury, to simulating seismic effects on Mars shows the breadth of impressive work going on at institutions all around the UK.

Within the Chemistry category that I entered, I was honoured to be selected as one of ten finalists to present my work at the event itself – and delighted to have been awarded the Gold Medal for Chemistry. Even in just this one category, the diversity of research was fascinating – everything from producing nanomaterials to treating brain cancers was on display.

We all faced a similar challenge – taking our very detailed and involved research and presenting it as a poster and a three-minute presentation that would speak to the broad audience this event has – including a number of parliamentarians who are interested to hear about the world of research, but have no science background themselves. It was particularly great to see Andy Slaughter – the local MP for the White City campus, where I am based – in attendance for the award ceremony, in addition to a range of other MPs and Lords. Knowing there are so many parliamentarians wanting to hear more about the latest scientific research is very heartening. Giving our usual academic presentations just wouldn’t be right for an audience like this.

In my case, that meant taking all the unusual concepts which make up my very interdisciplinary PhD – including G-Quadruplex DNA structures and Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy, not concepts that most people, even scientists, have ever heard of – and bringing them to life very quickly. Really what my research is about is finding the unusual DNA structures we’re interested in inside living cells – a challenge which is very tough, but by using a specialist method we have been able to achieve this and are now trying to unravel the important effects they have on a wide range of biological processes.

Thankfully, being in my final year, I’ve had the chance to attempt this before. Especially helpful were events run by Imperial’s Graduate School, challenging students to present their work in a brief and easily understood way. These courses and competitions are a really great opportunity to find the core of what makes your research exciting and how to put it across in an engaging manner. The only way to get better is to have a go. At Imperial and beyond there are plenty of opportunities out there, so putting yourself forward is something I’d recommend to any PhD student.

It is taking part in events like STEM for Britain which make it obvious that if we can’t tell a wider audience about all the research we do in a way they understand and find interesting, our work will never achieve its potential. That means being able to tell the wider public, and especially being able to tell policy makers, why they should care. At the very least, these are people who help decide what funding future scientific research receives, but more importantly they are the people who can help to take what we have discovered and do something about it on a wider stage. This ability to make a much bigger difference is part of the reason why, when I soon finish my PhD, I’ve become interested in being more involved at this interface between science and the world of policy.

Being part of a competition like this is very rewarding. There is prize money (which is always appreciated!) but there’s also the platform to get others excited about the research you devote your time to; the chance to see what lots of other researchers are discovering; and an opportunity to improve a skill set which I believe is hugely important to us all as researchers. It is an incredible honour to have had our research recognised at such a prestigious event, and it only gives me more motivation to get back to the lab to see what we can accomplish next.

For further information, you can view Ben’s poster and watch his 3-minute presentation, and check out the work of the other prize-winners here.

In this blog post, undergraduate Physics student, Anthea MacIntosh-LaRocque, reflects on her involvement in a StudentShapers project that focused on redesigning the two main foyer areas of the Blackett Building. The team included Student Liaison Officer, Dr Yasmin Andrew and postgraduate student Max Hart. Each member was keen to transform these spaces – not only in order to improve students’ opinions about their educational environment, but also to encourage a better sense of belonging and community.

In this blog post, undergraduate Physics student, Anthea MacIntosh-LaRocque, reflects on her involvement in a StudentShapers project that focused on redesigning the two main foyer areas of the Blackett Building. The team included Student Liaison Officer, Dr Yasmin Andrew and postgraduate student Max Hart. Each member was keen to transform these spaces – not only in order to improve students’ opinions about their educational environment, but also to encourage a better sense of belonging and community.

Walking around Blackett Laboratory during my first year always left me with a mixed bag of feelings. On the one hand, I was walking through halls bursting with innovative research and discovery. On the other hand, the building was outdated and disconnected from the very people who make the Department tick.

Take the cluster of black-and-white photographs hung in front of the main lecture theatre. In each frame sits a past Nobel Prize winner from the Department, and some of the photographs also show our Heads of Department over the years. These images are unquestionably important, but they are almost exclusively men and consequently not representative of the rich diversity of the Department I see around me today (or, furthermore, of the increased diversity we hope to have in the Department moving forwards).

On top of this, as students we never worked in the building. Instead, we’d scurry over to the library in search of some desk space and comfortable chairs that Blackett just wasn’t able to offer.

So, you can imagine how excited I was when I was approached by Dr Yasmin Andrew last March to work in a student-led team redesigning the two main foyer areas of Blackett over the summer, as part of a StudentShapers project. Obviously, as with all things over the past year, plans had to be changed in line with lockdowns, and the project was taken online before it had even begun. My first meeting with the other members of the team – Yasmin, Max and Josie – was over a Teams call in early June.

The only “boundary conditions” we were given for the project was the location. We weren’t even told a budget, simply that we needed to come up with a student-centred design that would cater to the twenty-first century Imperial student.

Building up a portfolio of perspectives on the space was essential in getting the project off the ground. We drafted up a survey to send to our fellow Physics undergrads and postgrads, asking a mixture of questions. It included survey “staples” asking what students did and didn’t like about the space, alongside more profound questions probing how the new space might incite belonging and community.

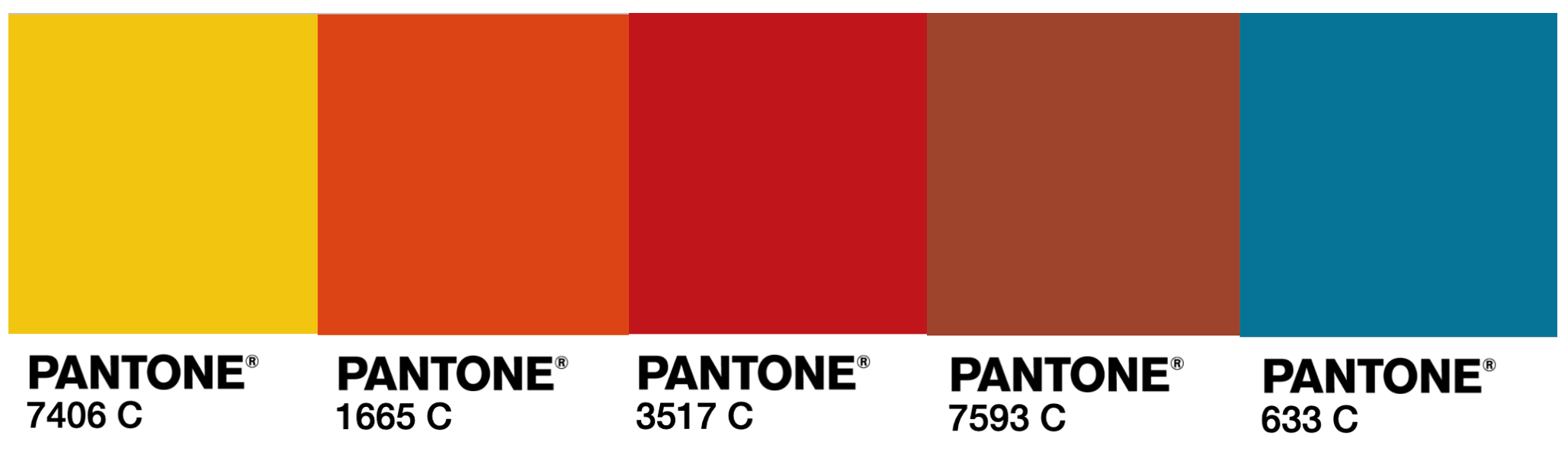

Using the survey as our basis, Max and I created two different designs using an online design software programme called FloorPlanner (think The Sims, but without all the people). These designs formed a foundation for subsequent one-to-one staff interviews and student focus groups. The ideas that came out of these discussions served as the creative fuel for the rest of the project. Eventually, we refined our designs and agreed on a colour scheme. The 1960s saw the completion of the construction of the Blackett laboratory building (1961) and a rapid expansion of the Department under under Professor Blackett’s leadership. We decided a 1960s theme to the refurbishment would respect and honour the historical time the department has to this era. You would be surprised how engrossed a team of physicists can become in details as minute as the colour of a table!

We presented our designs to departmental staff to get some more feedback, and then finally sent them along to the Building Operations team in early September. You can view some of the design renders that Max and I came up with over the summer below – click to make them larger:

During this academic year I’ve been lucky enough to keep working on the project: liaising with furniture designers, providing further student input, and communicating the work that was done to the wider Department, including my peers.

Ultimately, I feel very privileged to have been able to make an impact on a space that my peers and I will soon be interacting in on a day-to-day basis — public-health measures permitting, of course. It’s not certain whether the building works and furniture will be in place by the time we are back on campus. However, rest assured, behind-the-scenes implementation is already underway. I’m also very encouraged by the fact that the StudentShapers leadership has proactively encouraged student input, right down to the very last plug socket and blackboard.

It’s undeniable that working remotely has both its perks and its downsides. The flexibility it provides allows me to manage my working hours in a way that complements both my studies and the project’s pace. Having said that, we all found it difficult not being able to visit Blackett during the designing phase. While we had all spent plenty of time there, and had access to floor plans, visualising the spaces still proved challenging. Questions like, “Is that wall painted?”, and “Do we have a bench there at the moment?”, were recurring guests in our meetings.

Overall, participating in this project has been one of the highlights of my time at Imperial so far. Working on a project so different from anything I would have encountered during my degree has given me a prime opportunity to learn new skills, to think on my feet and expand the breadth of my university experience. Learning how to interact with staff, deal with data in the social sciences, and develop a project using constructive criticism are just some of the skills I’ve developed during this project.

Topping that is the feeling of satisfaction that comes with making a long-lasting impact on the physics community I am a part of. I think the décor we chose really speaks to this sense of community. We aimed to honour Blackett’s rich history, whilst staying relevant to the Department of Physics we know today. Once we can return to campus, I’m looking forward to watching how the spaces we are working on become the Department’s social hubs, and improved areas for collaborative learning. On a personal level, I can’t wait to be back on campus and make use of these spaces for much needed down-time between lectures and labs!

In my opinion the StudentShapers scheme, which runs a plethora of student-centred projects ranging from curriculum reviews to interior redesigns, is something all students should consider getting involved in. Not only does it provide you with the opportunity to take part in something not conventionally related to your degree, it also instils in you a sense of agency over your experience at Imperial. Moreover, the project has been a reminder to me that ultimately my time at Imperial is what I make of it. It’s so important to seek out exciting opportunities like this, to get stuck in, and to soak up everything the university has to offer.

By Anthea MacIntosh-LaRocque

The StudentShapers programme is open to all Imperial students across all Departments. Find out more about how to get involved.

Postgraduate student, Kitty Froggatt, is currently studying an MSc in Environmental Technology at Imperial’s Centre for Environmental Policy.

Postgraduate student, Kitty Froggatt, is currently studying an MSc in Environmental Technology at Imperial’s Centre for Environmental Policy.

In addition to her studies, she is also the group leader for Operation Wallacea expeditions at Imperial.

In this blog post she reflects on her own experience as an Operation Wallacea volunteer, and how it has impacted both her choice of further study and future career aspirations.

Throughout my life, I have consistently been made aware of the undeniable value, versatility, and wonder of the natural world. This all started from my experience growing up on a farm in Staffordshire, where values of environmental stewardship, and the vast natural capacity of even the smallest areas of land has been endlessly affirmed.

My academic studies – not only at school, but also as an undergraduate at the University of Bristol, where I studied a BSc in Biology – further heightened my enthusiasm for the natural world and provided me with valuable skills, fieldwork experience, and opportunities to review many aspects of the diverse and perplexingly complex world in which we live.

In my final year as an undergraduate I looked to the future, not only because I was considering my own career aspirations, but also because of the uncertainty of what is to come for ecosystems, organisms, and natural resources. Upon graduating from university, I found myself lost, lacking inspiration and direction for the next stage of my life. It was for this reason that I decided to volunteer for an overseas conservation and research programme with Operation Wallacea.

Operation Wallacea offers fantastic opportunities to partake in overseas biodiversity research projects. They operate in fifteen countries worldwide, including Indonesia, the Peruvian Amazon, South Africa, Madagascar, and more! Research Assistant positions, as well as opportunities for undergraduate and master’s level thesis research projects, are still available in both marine and terrestrial environments, and I really encourage fellow students to use their summer holidays to seek out and take advantage of volunteer opportunities like this if they can!

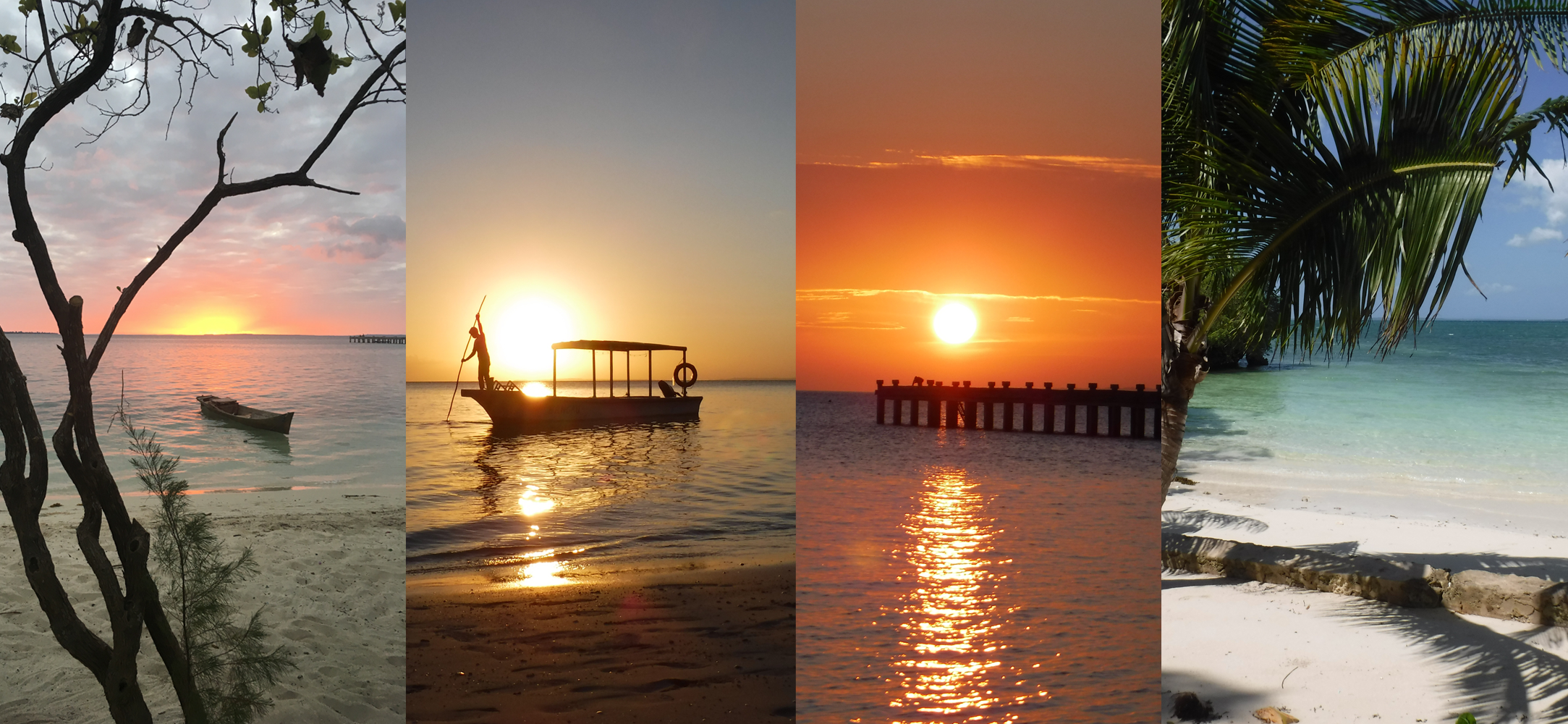

My volunteer expedition experience ran for two weeks, from 28 July – 10 August 2019, and was located on Hoga Island, part of the Wakatobi Marine National Park, South-East Sulawesi.

On my expedition I undertook a specialised course on Indo-Pacific reef survey techniques. We were given a detailed insight into the vast biodiversity, threats, and ecosystem function of this astonishing area. Along with this, the course provided the opportunity to practice organism identification and data collection strategies in the field, as well as achieving a PADI open water qualification.

The opportunity to experience a fragile marine ecosystem first-hand, and gain specialist knowledge of marine organisms present in this unique environment, inspired me to continue my travels in Indonesia, where I was then able to complete my PADI advanced diving qualification. The experience also motivated me to apply for a master’s degree specialising in sustainable development or environmental management. I hoped that this would further my interdisciplinary outlook on tackling environmental and sustainability issues and strengthen my knowledge of how policies and resources can be developed and implemented to limit further degradation and extinction.

Before completing the expedition, I was awarded the Alfred Russel Wallace Grant for Outstanding Field Ecologists and kindly sponsored by Premier Oil to take part in the project. As part of the award, I was invited to speak about my experiences at the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) in November 2019. Walking along Exhibition Road towards the RGS, which is located next to Imperial’s South Kensington campus, I fell in love with Imperial. I made the ambitious decision then and there that Imperial was where I would like to complete my MSc… and here I am!

My experience volunteering with Operation Wallacea provided me with an invaluable insight into how to uphold and implement social and environmental responsibilities, while efficiently conducting important conservation research. The project has helped guide my future career outlook and aided me in securing my place on the Environmental Technology MSc at Imperial. I could not recommend the experience and Operation Wallacea more highly!

The Mary Lister McCammon Summer Research (MLMC) Fellowship gives female university students a funded opportunity to spend the summer before their final year at university working on a ten-week research project with a leading mathematician or statistician. Participants get the chance to spend time with current PhD students to find out what studying a PhD is actually like, plus briefings on how to apply for a PhD and the kinds of programmes and funding streams which are available.

Katherine Holmes was a participant on the programme in summer 2019, and is now studying a PhD in Quantum Dynamics in the Department of Mathematics. In this blog post she reflects on how the Fellowship influenced her – both academically, and also on much more personal level.

Hello, my name is Katherine and I am a first year PhD student studying Quantum Dynamics with my supervisor Dr Eva-Maria Graefe.

Before Imperial, I studied on the MMath (Maths with Masters) course at the University of Nottingham (UoN). My undergraduate degree there was very positive – it was, after all, where I discovered my passion for Quantum Mechanics. I feel very thankful that UoN provided many opportunities to study the different branches of Quantum, and also thankful to be able to continue learning about the field as part of a PhD at Imperial. I’ve been doing the PhD for about four months now, and am genuinely loving it.

I feel humbled to say, however, that if it were not for the Mary Lister McCammon Summer Research Fellowship, I would not have had the self-belief to pursue a PhD. The MLMC Fellowship is a funded programme and I was part of the first cohort of during the summer of 2019. It brought together fourteen brilliant women studying mathematics from across the country to be treated as “pseudo-PhD students” for ten weeks. When I first heard about the opportunity, I got excited and nervous. “This sounds incredible!” I thought, “but am I really capable of this sort of research?” I had a fair few doubts about myself when I applied in the third year of my undergraduate degree. Specifically, I knew I had found my passion in theoretical physics and that I am good student, but was I good enough? This question of “am I good enough?” sprung in mind many times during my academic journey, largely because I have dyslexia, and that tore down my confidence that I could produce research and write a thesis.

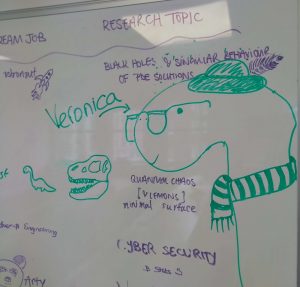

In the end, I decided to be bold and apply. I got accepted and, crying tears of joy, went to tell my parents! Thus, I began the best summer I ever had. The goal of the MLMC Fellowship is to simulate life as a PhD student, including giving a wage equivalent to a PhD stipend, which was enough to cover accommodation in Imperial halls, cost of living and a little extra spending money to have fun with. My cohort also had access to a computer room. It was given to us as an “office” but we spent just as much time treating it as a social space. Working along side the cohort was a pleasure. We all had backgrounds in wildly different areas in mathematics, which can be difficult to communicate. We were, however, all united in the friendly conversations we had about how we should have a Diplodocus as our mascot: her name was Veronica.

Each one of us had a topic to focus our research on, and we were also all paired with a supervisor with expertise in that area. Mine was Quantum Dynamics with Dr Eva-Maria Graefe and Dr Jessica Eastman. When we first met, we talked about bread and bikes before anything mathematical. Such a relaxed conversation made me feel very welcome. Then after a couple cups of tea, they suggested the research topic of “Quantum Billiards”. They knew I had MATLAB experience, so what if I made a code that simulated classical billiards, i.e. what you find in any good pub, specifically a model of a ball bouncing around a table. Then we make it quantum, where we make the ball tiny and we don’t know exactly where it is on the table, such that it’s in a superposition. That sounded exciting to me and I agreed to the topic.

So this was the beginning of the journey. I got into a good routine of coming into the office four days a week and working one day in the comfort of halls. The work was enjoyable and made me a MATLAB convert, so much so that I’m now looking forward to coding on the software during my actual PhD project.

Doing proper research is very interesting. Some days you’ll make lots of progress, some days you’ll get nowhere and other days you just want to scheme with fellow group members to buy a cohort teapot and make each other tea. One nice difference from being treated like an undergraduate compared to a postgraduate is, when doing a degree you are told regularly to constantly work hard, but during a PhD and similar projects there’s an emphasis on “don’t work too hard, look after yourself”, which is a healthy mentality to share. There is no doubt you are capable and hard-working, so you should also have fun and spend time maintaining your mental wellbeing – and sometimes a healthy approach to wellbeing means going to Argos at 2pm on a Tuesday to buy a tea pot.

We did have a little structure in our week. We had talks from speakers every couple of weeks about research opportunities and experiences, as well as “tea and chat” with current PhD students. They were very helpful and informative. The true highlight, though, was communication training with Justine Jones. These three-hour sessions boiled down to “applied improv”, taking the skills you develop in improvised acting and putting them to use in an academic setting. They were some of funniest moments of the Fellowship, and in the end we all become more skilled and confident giving professional presentations.

As the weeks went on, my confidence improved as much as my billiards codes improved. Some days I got stuck, but I had the regular contact and support of my supervisors to move past any hurdles. Solutions were discovered and codes finished. After two weeks we had classical billiards, and after five weeks we had quantum billiards. As if winning the game itself, I had a revelation: I was good enough to do a PhD. Not only did I complete the work, I really enjoyed it, and the insecurities that had held me back disappeared as I realised my own potential. The MLMC Fellowship changed my life because it was the opportunity I needed to show myself that I am good enough follow my passion and pursue quantum mechanics further.

We all feel we’re not good enough at some point in our lives, even though often we are already good enough. But knowing we are, and actually believing that, can be two very different things. Advancing in academia is a challenge that a lot of us won’t feel capable of. This fellowship is for women because there is a huge drop in the number of women taking part in Mathematics PhDs compared to undergraduate study. It’s hard to say why, but maybe it comes down to many of us thinking “I’m not good enough”.

My advice is, if you are a woman eligible for this Fellowship, especially if you find yourself unsure about your research skills, then apply. The Fellowship, of course, might be different in future than my experiences, due to the pandemic. But nevertheless, it will provide you the similar opportunity to see if a PhD is for you. In the end you have nothing to lose by trying. Maybe you will be a future Fellow. Maybe you’ll have a transformative time, and then maybe you’ll be walking the campus as a PhD student in years to come.

Applications for June 2021 are now open! Applications will close on 1 March 2021. Find out more about the programme and how to apply.

Due to the pandemic, last year’s programme ran entirely remotely, including all project supervision, communications training, seminars, and social activities. Our 2020 fellows reported that the summer was still both valuable and enjoyable. The format of the 2021 fellowship will depend on the COVID-19 situation this summer. If an in-person programme is possible, then we will offer this. If it is still necessary for the programme to be remote then this is what we will do.

In autumn term 2020, during the second UK lockdown, thirty students from the MSc Ecology, Evolution and Conservation programme were granted permission to go on a residential to Lundy Island, a 1×3 mile rocky outcrop off the Devon coast. During their time on the Island they learned essential field skills, and explored its natural history, behavioural ecology and the evolution of its resident house sparrows. So how was this expedition able to go ahead, and what measures were put in place to ensure everyone’s safety? In this blog, Course Director, Dr Julia Schroeder, and student, Fahmida Nitu, reflect on their experiences during the trip, and the planning that went into getting it off the ground.

You can watch the group’s video diary here!

By Dr Julia Schroeder – Course Director, MSc Ecology, Evolution and Conservation

As it took place during lockdown, the trip required meticulous organisation to ensure social distancing was maintained and that no government rules were broken. I had excellent support from the Faculty’s head of Health and Safety, Stefan Hoyle, and the Departmental Management Team – together we sorted out all the logistics to make the trip possible. This included, among other precautions, the testing of all participants for COVID-19 (all negative) and subsequent isolation before embarking on the journey, and the distribution of students among accommodation being matched with pre-trip household groups.

Lundy and its islanders were already practically quarantined from the rest of the UK, with the Island being closed from the beginning of the lockdown onward. This meant no flights and no boats. To get to Lundy, students took an exhilarating helicopter ride from the mainland – talk about social distancing!

By Fahmida Nitu – MSc student, Department of Life Sciences

The degree programme that I’m studying at Imperial – the MSc Ecology, Evolution and Conservation – is full of computational ecological courses, but that doesn’t mean we spend all our time sitting at our desks in front of computers doing models and so on. Recently we went to an island in the middle of the Bristol channel. Thanks to the Chevening scholarship, the cost of this exciting field trip was all covered.

At about 3500 BC humans first arrived on the Island of Lundy from mainland Europe. The Island is located off southwestern England in the county of Devon, and its biodiversity-rich landscape is isolated from the mainland, which has helped to keep its wilderness intact. Over time, large granites have built up over considerable parts of the Island.

After the outbreak of COVID-19, it remained closed for several months. However, we were lucky enough to get the opportunity to visit in November 2020! Before leaving on our journey, we were required to test for COVID-19 and fortunately the whole group tested negative.

We started our journey in the early morning of November 30. We were taken to the helipad of the Hartland point of Bideford. The journey from Imperial to Bradford took approximately five hours; from there it took only ten minutes from the Heartland to Lundy Island by helicopter! I was a bit nervous, but at the same time was amazed to see the beauty of the Bristol channel and the granite outcrop from the sky.

We started our journey in the early morning of November 30. We were taken to the helipad of the Hartland point of Bideford. The journey from Imperial to Bradford took approximately five hours; from there it took only ten minutes from the Heartland to Lundy Island by helicopter! I was a bit nervous, but at the same time was amazed to see the beauty of the Bristol channel and the granite outcrop from the sky.

After landing on the Island, we were split into several small groups and assigned to separate cottages for our stay. Each group was supplied with groceries that had been pre-ordered – in fact, the island always collects its groceries from the mainland. It only produces dairy products from its sheep farms.

The island is managed by Lundy Landmark Trust and is popularly called Puffin Island as puffins are the most common bird found there. Other waterbirds, sparrows, and starlings, plus wild horses, deer, and goats abundantly populate the Island too.

There are granite cottages for tourists to stay, a souvenir shop and also a tavern for community gathering. Lundy Castle is a 13th-century building that was always the residence of the Island’s owner and governors. It is still standing and represents its history; a church is also situated at the entrance to the Island.

I first spotted wild deer running over the grasslands and it was the first time I’ve ever spotted a seal in the wild! Sheep grazing here and there was also a common sight.

We were assigned group tasks related to our research projects, and we took part in the Lundy Treasure Hunt too, which was exciting! During our five-day expedition, we explored every corner of Lundy Island.

We are grateful that the Landmark Trust allowed us to visit the Island, enabling us to experience a real field trip, and also allowing us to complete our course module in biodiversity. Credit goes to our Course Director Dr Julia Schroeder for her dedicated efforts to get the approval to visit – thanks Julia!

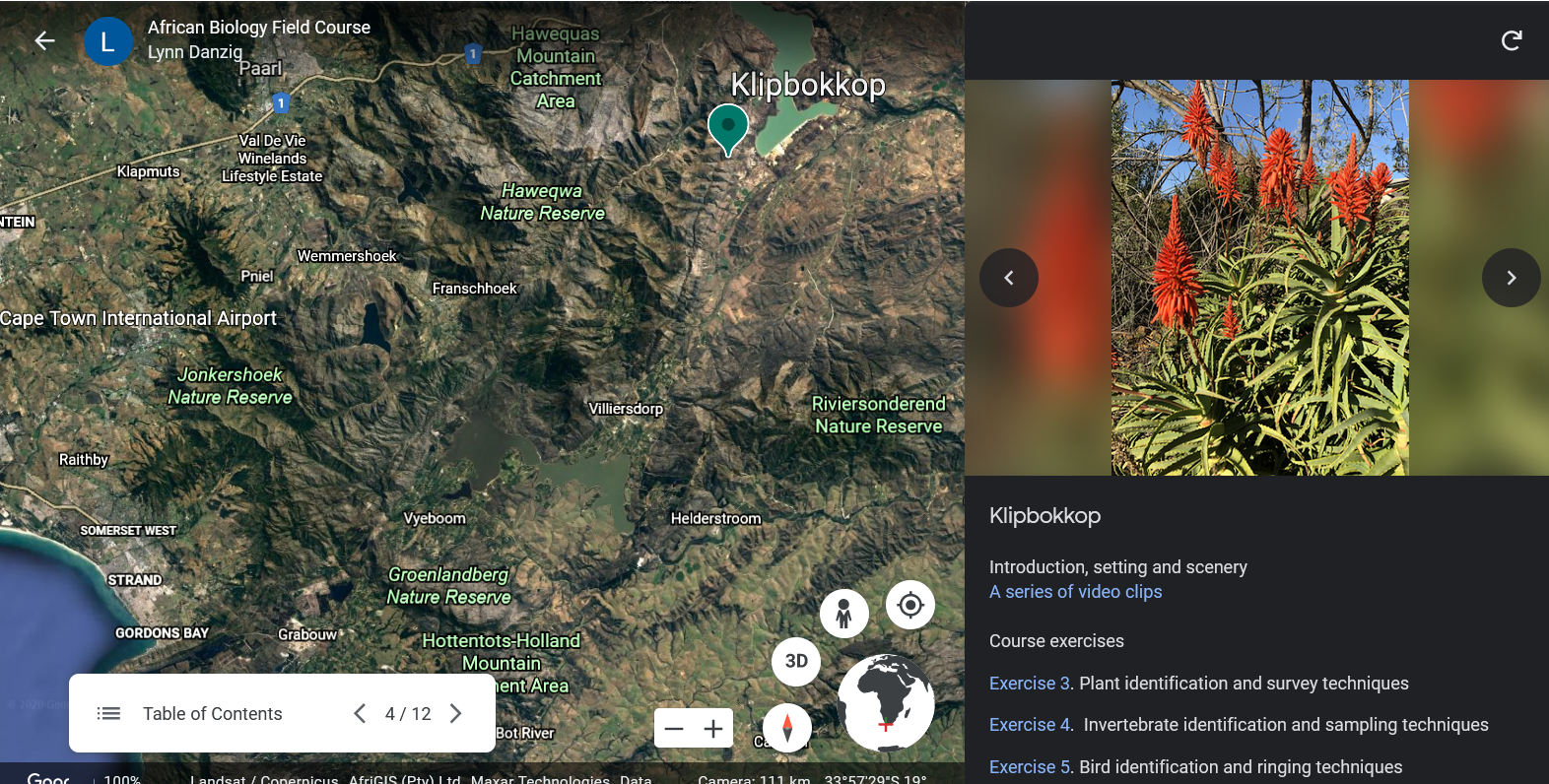

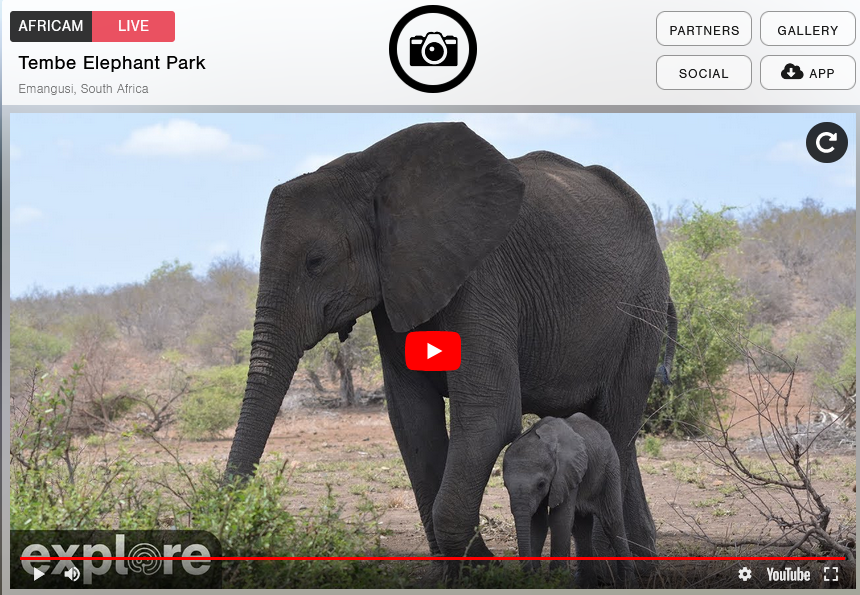

Third year undergraduates in the Department of Life Sciences can opt for an African Biology Field Trip module as part of their degree. Normally, this means that they get the opportunity to visit South Africa for two weeks, to learn more about the practicalities of biological research in some of the Earth’s most spectacular biodiversity hotspots. COVID-19, however, meant that in 2020 students haven’t been able to physically travel abroad for this first term module. Professor Vincent Savolainen, who has organised the course over the past decade, guided efforts to adapt it into a remote offering. He wanted to ensure that students not only to met their learning objectives, but also experienced as much of the nature of the field course as possible via a virtual tour.

In this blog post Kiran Gawali and Lynn Danzig, from the FoNS Ed Tech team, share insights into how they supported Professor Savolainen in rethinking the field trip. As well as working closely with Life Sciences teaching staff, the team hosted six undergraduate student interns over the summer, and keenly emphasise the value of including students in the educational design process.

In previous years, students on this course travelled to South Africa and visited a variety of different areas, from a fynbos vegetation in Klipbokkop Mountain Reserve, to wildlife havens like Botlierskop Game Reserve. Technology has played a key role in enabling this course to be run virtually, but in addition to making the most of multimedia, contributions from a range of people across the Faculty have been absolutely vital in piecing bits of the puzzle together.

On top of solutions suggested by the EdTech team, and soundbytes added by the AV team, our FoNS Ed Tech student interns were a really integral part of the design process. Their input – particularly in testing the software on different devices, in different regions, across different time zones – ensured that these new course materials would work as intended for all of our students, no matter where they were studying.

For the virtual field trip Professor Savolainen wanted to emulate the sense of a journey, so we helped him to implement this idea by creating a Google Earth tour starting at Heathrow Airport, landing in Cape Town, and then visiting a variety of different destinations. Moving eastwards along the coast to Knysna Phantom forest, the tour ends in the majestic natural parks in the north east of the country. Students are required to navigate and explore various locations. They undertake training activities that familiarise them with the ecology, evolution and conservation of South Africa’s fauna and flora, from Fynbos in the Cape to large game animals in savannahs. The broader course teaches field techniques through a series of online exercises, supplementary lectures and workshops with Imperial staff, and also interviews with local African scientists. The conclusion of the module enables students to work independently on their own mini-research project.

Students who have access to Google Earth were able to explore the surroundings of these sites and enhance their virtual experience of the module. There might be a variety of reasons, however, why some students might not have sufficient access to Google Earth, so developing an alternative solution was essential. This is where our interns – who are based all over the world – really became an invaluable part of the process!

They helped to test Google Earth on different devices, in different locations, with varied internet connection strength. They then got creative and developed a PowerPoint version of the tour to support students who could not access Google Earth. This involved designing a slideshow with the look and feel of a Google tour, along with a pop-up navigation bar providing a web-like experience that allowed the user to jump from one place to another from any slide in the slideshow. In this way, our interns’ careful thinking and anticipation of myriad potential user issues directly impacted and improved the user experience of the final product.

One of the techniques that the course teaches is how to get an idea of the numbers of a species in a particular area. The tech alternative to being physically onsite was to observe the animals via webcams, which are common in many wildlife parks in South Africa and elsewhere on the continent. Students who might not be able to access these cameras would work in collaboration with students who could, using screenshots captured from the webcams. In both the Google Earth and PowerPoint formats, we also embedded links to relevant resources on Blackboard, providing supplementary information.

The Internship Scheme has been developed not only to give current students an opportunity to gain practical skills and learn more about innovative approaches to teaching, but also to give our teaching colleagues insight into learning directly from the student perspective. This in turn benefits students of the future, whose modules will have been shaped by students before them.

Our interns have personal experience of teaching materials, and bring an enthusiasm, readiness to explore, and creativity to the process that can’t help but positively impact everyone involved. They’re also familiar with combining multimedia assets in a single resource, which really helps the team to push projects further and come up with unique solutions to problems.

We learnt about new features in PowerPoint because of their ideas in using it as part of their slideshow, for example. They also gave excellent feedback on the importance of good quality images. We introduced them to the Creative Commons search tool and collaborated on things like reducing file sizes of images to reduce the load time for slides that would be viewed online.

The team really values the time, work and enthusiasm our interns put into the scheme, and want them to walk away from the experience having honed graduate attributes and practical skills that will benefit them outside the university environment. We encourage the interns to keep online diaries during their time with us, a process that is intended to support them in becoming reflective practitioners. Reflective writing and applying metacognition skills is really valuable. Finding time for 1-2-1 meetings was challenging, so the diary format also seemed to provide an effective way for students to provide feedback and articulate their thoughts in an informal way. They served as a mechanism for staff to regularly check in with individual students and give personal support in a tight time-frame.

As part of the set-up of the internship scheme we also had a dedicated Teams site, regular Kanban meetings (designed to help teams work efficiently on complicated projects) and an MS planner to keep all processes and progress in check. Students were buddied up with interns who’d already completed the programme, who provided peer support, and helped hone their team working skills through lots of collaborative work across different time zones.

We’d like to say a big thank you to this year’s interns – it’s been wonderful to work with you and we hope you’ve enjoyed and learnt from the process as much as we have! We’re hoping to run the Internship Scheme again next year, so if you’re interested in working with us do look out for announcements in Summer term 2021!

Find out more about undergraduate courses and postgraduate taught courses in the Department of Life Sciences.

By Dr Kenji Okuse, Chair of EDI Committee, Department of Life Sciences

I came to the UK from Japan in 1995, and as a non-White member of society, had my own perspective on equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) issues, but to be honest I hadn’t thought about them seriously until I had the opportunity to get involved with the Department of Life Sciences (DoLS) EDI Committee in May 2019. I first took on the role of interim Chair, and now act as the Chair of the Committee. There are many complex and evolving issues in EDI, and my aim as Chair is to make our Department a fairer and friendlier place for everyone no matter, who they are or what role they have.

A world where everyone has equal opportunities and respects each other is what we hope for and work towards. However, it’s very difficult to achieve significant change towards that ideal without having proper structures in each level of our society designed to help us to get better at tackling the systemic issues that underpin it. (more…)