In our first post, we found out how our fashion trends are having a serious impact on our planet. In our second instalment, we investigate how the fashion industry needs to urgently change, and how it is showing promising signs that it is, albeit slowly, starting to become more sustainable.

By Nadin Moustafa, PhD student in the Department of Chemical Engineering.

As explained in my first post, it is becoming increasingly blatant that the fashion industry, and specifically the way its operating in terms of fast fashion, is detrimental to the environment. It is accountable for 10% of the CO2 emissions globally (UNEP, 2018), it contributes to 31% of the ocean’s plastic pollution (IUCN, et al., 2017) and a truck of clothes is thrown in a landfill every second (UNEP, 2018). It has been estimated that 1.13 million tonnes of clothing was purchased in the UK in 2016, which is an increase of almost 200 thousand tonnes since 2012. It is clear the fashion industry is not going anywhere; they do however need to work towards sustainability. UK citizens discard around a million tonnes of clothes per year (House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee, 2019), considering that they buy a little over a million tonnes per year – there is a clear need for circular economy. Thus, companies need to rethink their traditional linear business models and work towards a circular economy, which is challenging. Circular economy in the fashion industry requires a lot more work than just recycling and reselling clothes and even then, recycling clothes is not that simple.

Circular Economy in Fashion

To achieve circular economy in the fashion industry, companies need to consider several factors including collection procedures, textile recycling, the actual design of products and strategies for resale. Those “action points” were highlighted at the Copenhagen Fashion Summit 2017. As of June 2018, 94 companies signed the 2020 Circular Fashion System Commitment, representing 12.5% of the global fashion market. The 2020 commitment includes the following action points:

- Action point 1: Implementing design strategies for cyclability

- Action point 2: Increasing the volume of used products collected

- Action point 3: increasing the volume of products resold

- Action point 4: increasing the share of products made from recycled textile fibers.

Business models are expected to integrate reuse and resale into their strategies due to economic and environmental benefits. 95% of the clothes discarded can be recycled or reused. Increasing the life cycle of products by as little as 9 months through reselling reduces waste, water and carbon footprints by 20-30% each (WRAP, 2012). The businesses also have to gain since the apparel resale market share is USD 20 billion and is forecasted to reach USD 41 billion by 2022. This also aligns nicely with shopping habits, where 9 million more women bought second-hand in 2017 when compared to 2016 (ThredUp, 2018). That said, reselling does come with its challenges mainly including the consumers’ perception of used clothing. Another challenge is uncertainty of quantity and quality of products from collection schemes. Global collection rates of textiles are as low as 20%, hence the majority ends up in landfills and incinerators (Global Fashion Agenda & Boston Consulting Group, 2017). Collection schemes would need to consider incentives, transportation, sorting and whether the item will be resold, repaired, recycled with hopefully a small percentage going to incineration or landfill.

What do businesses need to do to achieve circular economy?

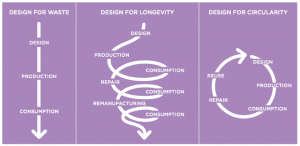

Circular design requires businesses to consider their end-goal when it comes to their products. For example, the company can either design for durability where the aim is to extend the use of a garment to multiple owners. And on the other hand, a company can design for circularity where the aim would be to enhance recyclability or biodegradability.

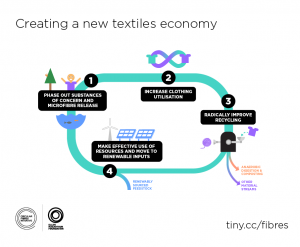

Recycling requires technology developments that will incorporate disassembling and then regenerating into new yarn. However, there is still yet to be commercial scale processes that are technically and economically feasible. Currently, less than 1% of the material used to produce clothing is currently being recycled; even though there is potential to tap into the current loss of USD 100 billion from wasted materials (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017).

Implementing such measures would not necessarily exacerbate fast fashion. It would mean that the fast fashion still exists from the consumers’ perspective, but it is slow from an environmental perspective.

Bibliography

UNEP, 2018. Putting the brakes on fast fashion. [Online]

Available at: https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/story/putting-brakes-fast-fashion

IUCN, Boucher, J. & Damien, F., 2017. Primary microplastics in the oceans: a global evaluation of sources. [Online]

Available at: https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/46622

House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee, 2019. Fixing Fashion: clothing consumption and sustainability. [Online]

Available at: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmenvaud/1952/1952.pdf

WRAP, 2012. Valuing our clothes: The true cost of how we design, use and dispose of clothing in the UK.. [Online]

Available at: http://www.wrap.org.uk/ sites/files/wrap/VoC%20FINAL%20online%202012%2007%2011.pdf

ThredUp, 2018. ThredUp 2018 resale report. [Online]

Available at: https:// www.thredup.com/resale

Global Fashion Agenda & Boston Consulting Group, 2017. Pulse of the fashion industry. [Online]

Available at: http://www.globalfashionagenda.com/ download/3620/

Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017. A new textiles economy: Redesigning fashion’s future. [Online]

Available at: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/A-New-Textiles-Economy_Summary-of-Findings_Updated_1-12-17.pdf

Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017. A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future. [Online]

Available at: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/A-New-Textiles-Economy_Full-Report_Updated_1-12-17.pdf