By Sarah Kakadellis a LISS DTP PhD student and a member of the second Transition to Zero Pollution PhD cohort and the SSCP DTP

Let’s face it: we live in a plastics world. Plastic pollution is doubtless a major societal challenge that raises serious questions about the sustainability of modern consumption patterns. The increasing amount of plastic waste generated each year, dominated by single-use plastics, has created an ecological and waste management crisis. Yet in difficulty often lies opportunity, and throughout history humankind has demonstrated its ability to overcome challenges with ingenuity. In the context of plastic pollution, recognising the ripple effects of a fossil-based economy – conventional plastics are traditionally made from crude oil – alternatives materials loosely referred to as bioplastics, have emerged on the market. But ‘bio’ doesn’t necessarily mean more sustainable and any material substitution must be carefully assessed. My PhD aims to assess the sustainability of these novel bioplastics to ensure they contribute towards tackling the plastics issue, rather than exacerbate it.

So far, my research has addressed the conflicts that emerge as we shift from conventional to bioplastics, while uncovering some of the opportunities too. Life-cycle thinking is at the core of my approach, which helps me look at the issue more holistically. For example, bioplastics are often biodegradable (not all of them are!), which makes them compatible with food waste recycling. However, this potential can only be fulfilled with an adequate and coordinated waste collection system. My latest findings highlighted the concerns over the suitability of biodegradable plastics in food waste treatment strategies, calling for increased collaboration between industry, academia and policy.

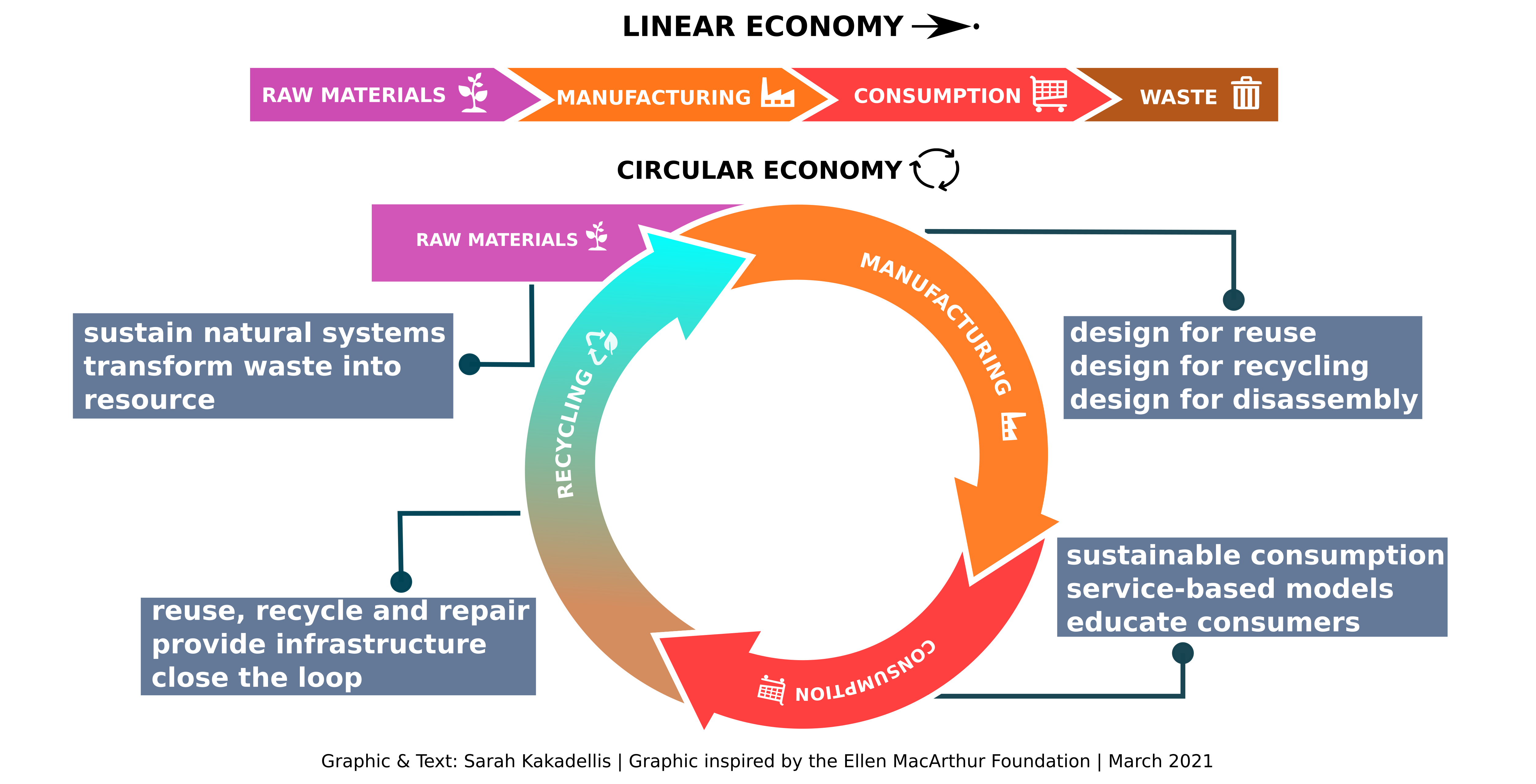

Working in a topical and highly mediatised research area is both a blessing and a curse. People immediately connect with the issue of plastic pollution, and tend to show genuine interest in the outputs of my work. However, it also means being acutely aware of all the false promises, misleading claims and unintentionally detrimental effects of public shunning of plastics. Ultimately, we need to recognise that achieving sustainability requires a systems-thinking approach. As Albert Einstein put it: “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used to create them”. In practice, this will mean redesigning our linear consumption model, rather that retrofitting the system at the very end.

The infographic below covers some of the concepts explored here, in common parlance. Thinking about the big picture, my research aims to fulfill the ambitions of a circular economy, which is essentially about keeping materials and products inside the loop for a long as possible.