Deus Ex: Bodies & Post-Human Bodies

Deus Ex: Medical Revolution

By Tomas Rawlings

Originally written in September 2011

A game with a fusion of ideas – from William Gibson’s Neuromancer ideas of cyberpunk, age-old conspiracy theories, global pandemics, dystopia futures, as well as the upheaval of rapid technology development.

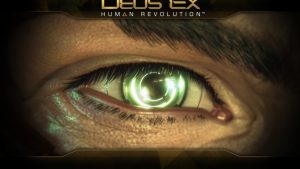

If, like me, you’re a gamer then you probably already know of the release of the hugely anticipated action game ‘Deus Ex: Human Revolution‘. If you’re not quite so geeky then let me introduce it; the game is a follow on (a prequel to be exact) to one of the most highly rated video games of the last 20 years. Both games are a fusion of ideas – from the cyberpunk ideas of William Gibson’s Neuromancer, age-old conspiracy theories, global pandemics, dystopia futures and the upheaval of rapid technology development. The original game received huge praise for the depth of its story-telling and the excellent game design that meant problems could be solved by other means than combat, such as stealth or dialogue. The original game featured a number of biomedical narrative themes – a deadly virus called ‘Gray Death’ that had ravished the human population and short global supplies of the vaccine that fights it. But crucial to both the gameplay and the story was the idea of nanotechnologically-augmented human beings. This idea of transhumanism – of the technological ‘hows’ and the ethical ‘whys’ of augmenting the human body in ways far beyond that which our genetic inheritances has endowed us, are also critical elements of the current game. Here’s the game trailer for Deus Ex: Human Revolution:

One of the interesting things that the trailer does is draw lines between the vast advancements of augmentation technology and the fears we may have about its impact and control on our societies and within ourselves. If you’ve watched the trailer you may have noticed the allusions that it draws between the advancing augmentation technology, the birth of modern anatomy from the 16th to the 18th century, and the myth of Icarus.

These are some of the narrative themes that are used to explore the many issues raised during the course of the game and the accompanying novel. The game’s director talked of these issues in a recent interview, remarking;

The Icarus myth dealt with Icarus being given wings to fly. But the wings were made of wax and he was perhaps not ready for such a gift; so in his haste, he flew too close to the sun which melted his wings and he fell to earth and his death. This story parallels our Deus Ex universe where mankind is using mechanical augmentations but there is still much to be determined in terms of their effect on society and the ultimate direction it will lead us in. The progress of technology and the advent of mechanical augmentations has offered mankind many exciting new possibilities but also many dangerous ones as well. … It’s a time of wonderful advancements but also much unrest as the general public, governments, and corporations all struggle to come to terms with the new possibilities.

The new Deus Ex game is a prequel and is set in 2027, 16 years from now and 25 years before the events of the original title. What is also interesting is that the game postulates a number of human augmentations for 2027 that, while currently are science-fiction, are well on the road to becoming science fact. For example the game’s main character, after suffering the loss of limbs, has not only fully functional replacements transplanted, but ones whose prowess far exceed the original limbs. How possible is this technology? The answer is very possible; just last month a schoolgirl from Swindon became the youngest person in Europe to be fitted with bionic fingers. Her father remarked, “We’d go out as a family and people would stare for the wrong reasons, they stare now in amazement.”

Games website, Beefjack opened this discussion to new audiences who might normally be swapping tips for improving their high-scores in Modern Warfare 2 and engaged them in looking at the fictional augmentations that players would experience in the game against what we all might see for real. Bionic eyes are one of the examples;

In real life, a range of research teams and companies worldwide are developing similar devices, mostly using externally-mounted cameras linked to a chip implanted in or on the eye, with early human trials looking positive. At the moment, the devices are relatively low-resolution, and designed to treat conditions involving damage to the retina such as macular degeneration and retinitis pigmentosa. Resolutions are gradually improving, though, and cameras small enough to fit into an eyeball already exist. Even if the implants don’t improve radically by 2027, there may be other sources of augmented reality overlays, such as contact lenses with displays worked into them. Such devices are currently under development, with a team at the University of Washington having trialled an early prototype in animals to assess the concept’s safety.

The technology for bionic replacements and augmentation is advancing fast. The debates around this technology are too, witness the debate around if it is fair to allow sprinter Oscar Pistorius, who runs with carbon-fibre legs, to complete with able-bodied athletes. IBM has made further progress towards mimicking the human brain’s functions by developing the very Blade-Runner sounding ‘neurosynaptic computing chips‘.

Some may be temped to dismiss video games as a frivolous pastime, but Deus Ex shows us that they are more than capable of taking complex debates and presenting them in a form that both entertains and informs. Deus Ex also follows the path set by other artists and media forms in holding up a mirror to our contemporary fears and hopes for technology and reflecting back one possible image of what may become of us. The future, it is said, is unwritten but thanks to games like Deus Ex and our imaginations, it can be played…

Posted with kind permission of Tomas Rawlings who is a Video Games Consultant for the Wellcome Trust.