It has been a long time since I talked extensively about the real reason I am in Cape Town. I have been at the University of Cape Town for 8 weeks now, with just one more week to go! It will be incredibly sad to leave as I have had an amazing time in this city and met lots of interesting and generous people at the university.

As I said at the start of my blogs, I am doing a research project looking at the effect of froth flotation on coal. This has been focused on two coal samples from coalfields in the North East of the country in areas called Waterberg and Witbank.

At the start of the project, a typical day was spent in the lab collecting data from froth flotation experiments or preparing samples for other analytical methods. Several chemical reagents were used during flotation and the dosages of these were varied to determine which was the most effective and how their individual chemistry interacted with each of the coal types. After each flotation, the liquid concentrate that is collected was dried and weighed, before being sent off for analysis to determine how much sulfur has been removed (the main aim of the project).

Over 120 samples were sent off to the Analytical Lab in the Chemical Engineering Department, as the analysis must be done using a particular machine that is only available in one of the labs. This took over three weeks to be completed (understandable for so many samples), but the results will now form a major part of the final project write-up, which has now reached over 40 pages in length!

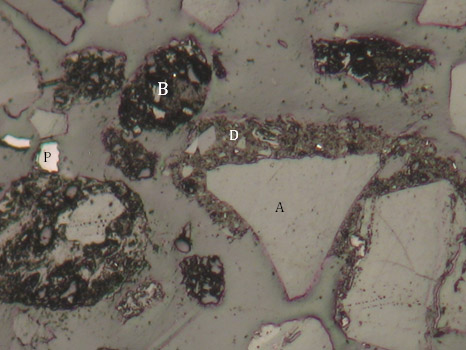

As well as flotation experiments, the coal samples have been made into blocks that are observed under a reflected light microscope to determine the composition of each in terms of their sulfides (the acid-generating minerals causing the initial problem of acid rock drainage), the relative proportions of bright and dull coal (usefully, bright coal is less bright) and the amount of ash.

This type of work could potentially be very useful to the department’s research and to the mining industry as a whole, as a simple evaluation of the coal mineralogy could be linked to the success of flotation to remove sulfides. Therefore, this could save a significant amount of time and money for the industry, as flotation would only need to be implemented on the coal waste if a mineralogical study showed that it would be worthwhile.

This makes the work incredibly engaging as it contributes to a branch of science that is innovative and growing and is likely to help the mining industry in the future. At present, only 5-10% of South Africa’s mining industry (and 20% in the world) uses froth flotation to remove sulfides prior to waste disposal, but research in this field at UCT hopes to one day improve these figures.

Fingers crossed that all made sense! One more week to go of finishing the written report, a bit more microscope work and a some final analyses in the lab, before leaving this amazing country and being back in the UK (it better not be grey and raining!)

I hope that you enjoyed this instalment, and that is was a little different from my tourist blog of Cape Town thus far.

Cheers,

Harry