Can the UK meet the government’s target of offering all adults a covid-19 vaccine by 31 July?

The Prime Minister Boris Johnson has set a target of offering a first dose of a covid-19 vaccine to all adults in the UK by the end of July 2021. What do we need to do to achieve this target? The first step is to ensure we have enough vaccines to offer first and second doses to all adults. There are around 53 million people aged 18 and over in the UK. If everyone took up the offer of a vaccination, we would require about 106 million vaccine doses, along with a small amount of vaccine for people under 18 who are classed as clinically extremely vulnerable.

Currently, we are using two vaccines in the UK: from AstraZeneca and Pfizer-BioNTech. A third vaccine from Moderna has been licensed in the UK but is not yet in use. Other vaccines—such as the candidate from Novavax—are in the late stages of development and approval; and may come into use in the UK by the early summer. The government will need to ensure that these companies can supply enough vaccines for use in the UK to meet its target date of 31 July.

How quickly do we need to vaccinate the UK population to meet the target? By 20 February, the UK had administered around 18 million doses of covid-19 vaccines (17.2 million first doses and 0.6 million second doses). This means that we need to administer around a maximum of another 88 million doses of vaccines if all adults in the UK accepted the offer of a vaccination and received two doses of vaccine.

In recent weeks, about 2.9 million doses of vaccine have been administered each week in the UK. As there are around 23 weeks until 31 July, we would be able to administer about a further 66 million vaccine doses by the target date, bringing the total doses administered to 84 million. This would be sufficient to provide all 53 million adults in the UK with at least one dose and also to provide 31 million of these people with two doses of vaccine.

Maintaining the same pace of vaccination after July would allow all adults in the UK to receive two doses of vaccine by mid to late September. In practice, we may need less than a total of 106 million doses of vaccine to immunise adults in the UK because not everyone will take up the offer of a covid-19 vaccination. Hence, the target of “offering” all adults in the UK a first dose vaccine by 31 July looks achievable if the supply and administration of vaccines can both be maintained at their current rates.

It’s also worth considering whether the UK should be more ambitious in its target. For example, if there was sufficient capacity in the NHS to offer 3.8 million doses of vaccine per week —an increase of 31% on the current vaccination rate—and vaccine supplies to allow this, all adults in the UK could receive two doses of vaccine by 31 July. In either scenario, 2.9 million doses weekly or 3.8 million doses weekly, the UK would have offered two doses of vaccine to all adults in the UK before the Autumn and thus would be better prepared for any seasonal increase in covid-19 infections than it was in 2020.

Maintaining an average of 2.9 million vaccinations per week for the next 23 weeks is ambitious, but it looks practical if vaccination sites can be guaranteed sufficient doses of vaccine. Vaccination sites will also need to have deliveries timetabled well in advance so that clinics can be planned and patients booked in for appointments. It’s therefore critical that we avoid the problems seen in the earlier phase of the vaccination programme, when deliveries of vaccines to vaccination sites were often arriving late or being cancelled at short notice. This created logistical and planning difficulties for vaccination teams, as well as being very inconvenient for patients who had their appointments cancelled.

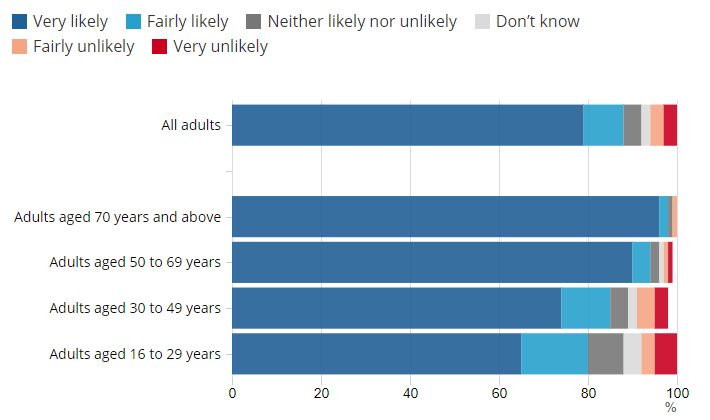

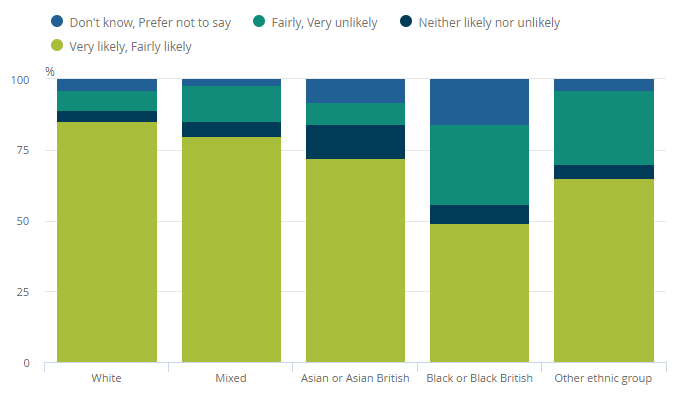

We also need to bear in mind that we have thus far been vaccinating groups of people, such as older or clinically vulnerable people and frontline healthcare professionals, where vaccine uptake has been very high. As we start to vaccinate younger, healthier groups of people, we may find vaccine uptake is lower than in older people because of greater levels of vaccine hesitancy. We need to ensure that we engage with vaccine hesitant groups—whether these are younger people or people from ethnic minority communities—to achieve a very high uptake of covid-19 vaccination. Broad population coverage is the vaccination programme’s best hope of success in helping to limit the spread of covid-19, allowing the UK to gradually relax its covid-19 control measures.

At this point, we also don’t yet know if booster vaccines will be required later in the year or in 2022 to deal with the effects of any decline in immunity following vaccination, or to provide protection against new variants of SARS-CoV-2 if older vaccines are less effective. If this is the case, we will need to put in place the infrastructure to deliver additional doses of vaccines to all adults in the UK, making the covid-19 vaccination programme like the influenza one but on a much bigger scale. It’s also possible that we will have vaccines licensed for use in children later this year, which will further increase the number of people who need to be vaccinated. The size of the covid-19 vaccination programme and its importance in allowing a return to a more normal way of life in the UK means that it must be meticulously planned and adequately funded for the indefinite future.

In conclusion, the government’s vaccination target looks achievable if it can guarantee sufficient supplies of vaccine; improve the planning of deliveries to vaccination sites; and provide vaccination teams with the required financial, administrative, and personnel support. This needs to be done at the same time as the NHS deals with all its other emergency and elective work, as well as with the large backlog of work caused by covid-19. As the majority of covid-19 vaccines have been delivered by primary care teams, particular emphasis must be placed on supporting NHS primary care during this period to ensure successful achievement of the vaccination target.

This article was first published in BMJ Opinion.