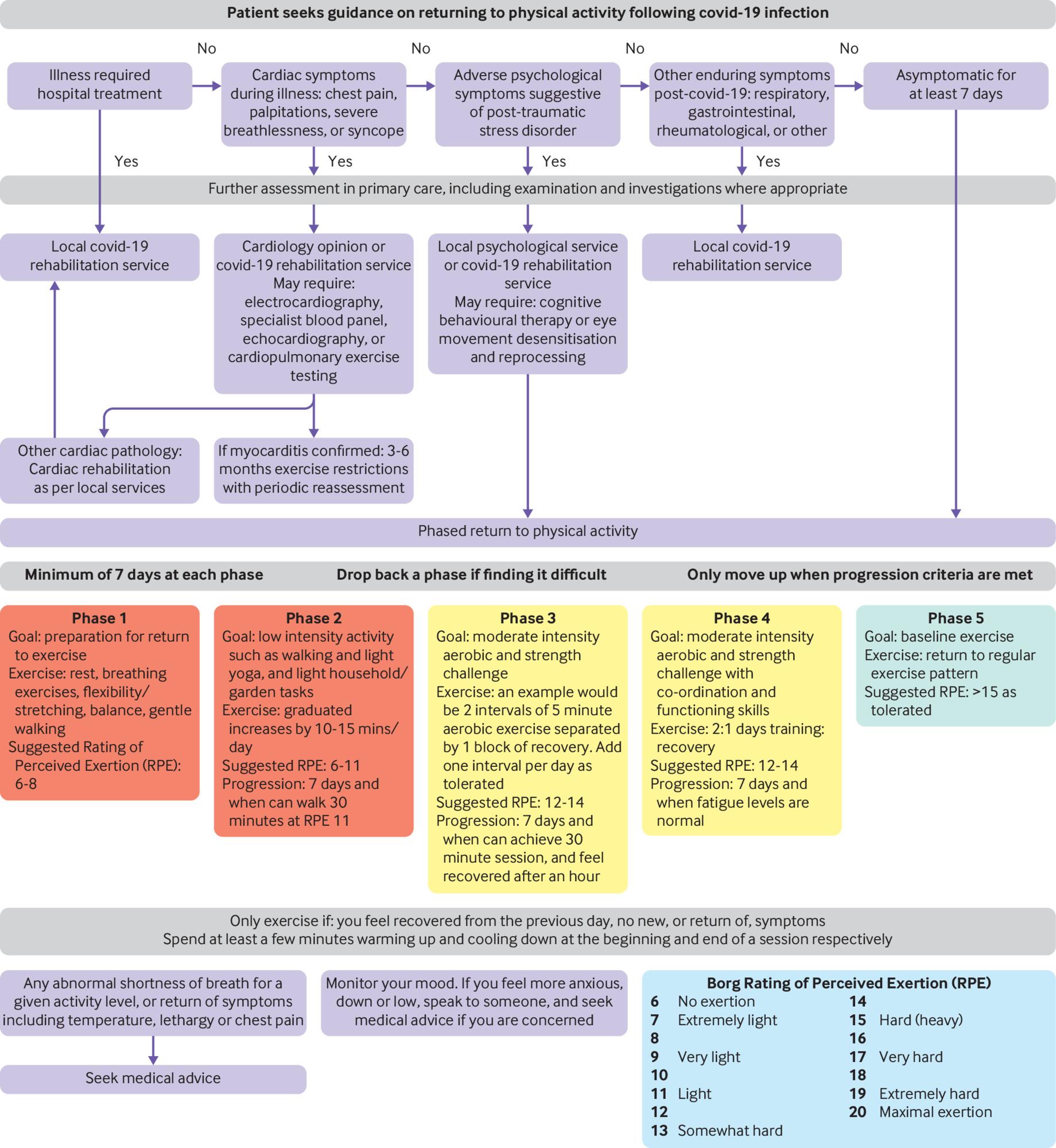

Returning to physical activity after a Covid-19 infection

In an article published in the British Medical Journal, we discuss returning to physical activity after a Covid-19 infection. A risk-stratification approach can help maximise safety and mitigate risks, and several factors need to be taken into account. First, is the person physically ready to return to activity? In the natural course of Covid-19, deterioration signifying severe infection often occurs at around a week from symptom onset. Therefore, consensus agreement is that a return to exercise or sporting activity should only occur after an asymptomatic period of at least seven days, and it would be pragmatic to apply this to any strenuous physical activity. English and Scottish Institute of Sport guidance suggests that, before re-initiation of sport for athletes, activities of daily living should be easily achievable and the person able to walk 500 metres on the flat without feeling excessive fatigue or breathlessness. However, we recommend considering the person’s pre-illness baseline, and tailoring guidance accordingly.