Justine is taking part in Imperial’s COVID-19 vaccine clinical trial – here she shares her experience of receiving the first dose.

It’s a strange feeling that as I write this, the cells in my arm are reading a message that scientists planted there just hours ago.

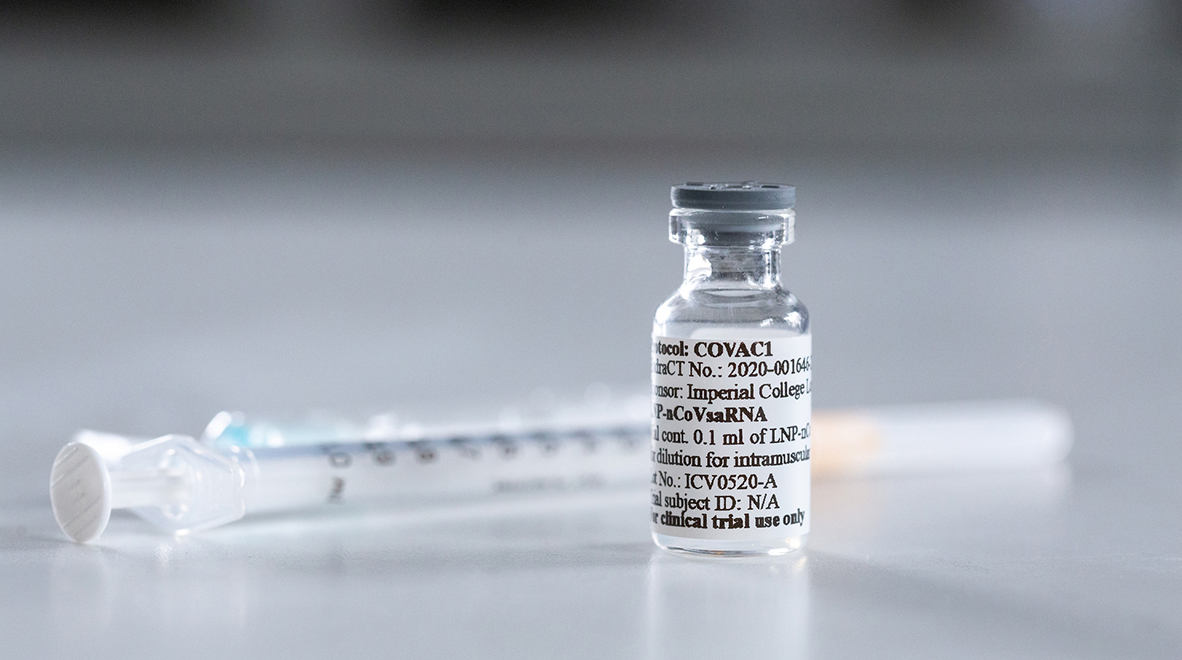

That message – a strip of genetic code – contains the recipe for making part of the virus that causes COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2. This is the ‘spike’ protein that the virus uses to lock on to cells and invade them. The hope is that by telling my cells to churn out this molecule, my immune system will launch an effective and lasting response that could make me immune to the coronavirus.

That’s the theory, anyway; we won’t know whether this experimental vaccine works until scientists have carried out rigorous clinical studies and gathered enough data to be confident of how safe and effective it is. And today I was part of that clinical research.

I’m one of 120 people who have so far been selected to take part in one of the earliest phases of a clinical trial that’s testing Imperial’s newly-developed coronavirus vaccine. As soon as I spotted that the trial was recruiting participants, I immediately slotted my details into the online form to express my interest in joining, and eagerly awaited a response.

It wasn’t long before I received a reply that I might be eligible, and that I’d need to come for a screening session to find out. Within a week I was at the research facility, running through what seemed like endless forms to find out details of my medical history. As the research is at such an early stage, they’re very strict with who can join and want to make sure that participants are fit and healthy, and not pregnant in case there are any risks.

After racking my brains to remember details of the operation I had as a youngster to fix my broken arm, I was given a pregnancy test, a few prods and pokes, and had a handful of blood samples taken for a battery of tests. I was told that if I’m eligible, I’ll need to come in almost every week for two months, and then a few further visits throughout the following 12 months. I couldn’t help but think: Is this really worth the effort?

For me, signing up wasn’t really a selfish endeavour; even if I did make it on to the trial, there’s no guarantee that the vaccine would be a success. It’s a very new technology, and we’re still learning so much about this novel virus. But the chance to take part in ground-breaking research that could change the course of history overrode any apprehension I had. And as humans are the best way to study diseases and new treatments, medicine can’t advance without trials in people.

About a week after my screen I was excited to receive an email offering me a place on the trial. I’d ‘passed’, as it were, with a full bill of health; which was reassuring! I accepted immediately and booked my place.

On the day, I arrive a little dishevelled having cycled across London to get there. The clinic was quiet and straight away I was ushered by a member of the team into a large, well-lit room with a giant blue chair I was to get to know well over the next three hours. I have a strange mixture of nerves and adrenaline.

A very kind nurse gives me a few minutes to calm down before I’m given another mini screen. I’m told they need to do another pregnancy test and check my vital signs; if anything is awry, I wouldn’t be given the vaccine. Happily, everything is fine once again.

The Chief Investigator for the trial, Dr Katrina Pollock, then pops in and introduces herself. I’m desperate to know which dose group I am in.

“For this trial, you’re going to be blinded, which means that we will know which dose you’re getting, but you won’t,” she tells me. Dr Pollock explains that the 105 participants will be split into three groups, who will receive one of three doses that had already been tested in 15 people as part of a ‘dose-escalation’ study to find out whether people have any reactions to different amounts of the vaccine.

The reason I’m not allowed to find out which dose I’ll be getting is so that it doesn’t influence how I report I’m feeling afterwards. For example, if I knew I was getting the highest dose, would I start to assume I’m feeling worse?

The final step before getting vaccinated is taking blood for a suite of tests. I’m not squeamish, but I begin counting the vials as the nurse prepares my arm with a tourniquet. “14?!” I squeak. “Yes, I’m sorry!”

These are my baseline blood samples to compare throughout the study, I’m told, looking at how my immune system and organs are functioning.

While the team prepares my dose, I’m reassured that I can drop out of the trial at any point should I wish. That’s not something I intend to do, as I want my results to be useful for the team. But you never know what life may throw at you, so it’s good to understand that I’m not obliged to continue if I can’t or don’t want to.

The nurse finally brings the vaccine over and I’m pleased to see that both the needle, and the volume of liquid, are very small. “Sharp scratch” and it’s over; I’m vaccinated. It was very undramatic.

https://twitter.com/ImperialMed/status/1283823459051737091

Dr Pollock tells me that they’ll now be looking for three different things as the trial continues over the next year; how safe the vaccine is, whether my body tolerates it, and how my immune system responds to it. “The vaccine is basically a training system for your immune system, to prep it for any encounters with the coronavirus,” she says. In particular, they’re looking for antibodies that could thwart the virus. But they’re not expecting to see much of a response until I come back for a booster shot in three weeks, when I’ll be given the same dose again to help better engage my immune system.

I hang around for an hour while I’m kept under a watchful eye, texting my family to let them know the deed is done. And then I’m free to go home, symptomless and feeling proud to have done my bit for medicine.

I’ll be tracking my symptoms and how I’m feeling over the following week, and the team will call to check in on me. I wish I had a portal into my cells to check out how my body is reacting to the vaccine. For now, I’ll just have to wait.

While Justine works at Imperial College London, all views expressed here are her own. She went through the same application and selection processes as all other participants on the trial.