This Salt Awareness Week, Dr Queenie Chan puts the salt intake guidelines to the test and looks at the reality of curbing salt intake for better heart health.

Salt and sodium are often used interchangeably, but they’re not exactly the same thing. Sodium is a mineral that occurs naturally in foods or is added during manufacturing or both. Table salt is a combination of sodium and chloride, which was one of the most valuable modes of currency in ancient times. It has been used to preserve food for thousands of years and it is most commonly associated as a form of food seasoning. Salt also plays a role in food processing, providing texture and enhancing colour.

Can’t survive without it

Our body can’t live without some sodium. Sodium is an essential nutrient for maintenance of fluid balance and plasma volume, transmission of nerve impulses, contraction and relaxation of muscle (including the heart and blood vessels) and normal cell function. It doesn’t take much to do this. Typically about 15% of the sodium we consume comes from foods that naturally contain sodium, such as celery, beetroot, milk, meat and shellfish, and some is added when we’re cooking and eating. Overall, 70% of the sodium we eat comes from salt added to processed and pre-packaged foods, restaurant foods and table salt.

Salt and blood pressure

High blood pressure is a major risk factor for many diseases, such as heart failure, stroke and coronary artery disease, affecting more than 1 in 4 adults in the UK. Hundreds of studies have looked at the relationship between salt intake and blood pressure. For example, the INTERSALT Study involving 10,079 women and men ages 20-59 from 52 population samples in 32 countries, showed significant relationships between sodium and blood pressure, and prevalence of hypertension. This study also reported that four very low salt intake populations had little or no upward slope of blood pressure with age. For example, the Yanomami people of the Amazon rainforest with just 0.5g salt a day. In general, research shows that cutting back on salt lowers blood pressure and reduces the chances of having a heart attack or stroke.

High blood pressure usually produces no symptoms and our body can tolerate it for a long time. How salt affects your blood pressure depends on your genes, your age, and your general health. However, high blood pressure doesn’t just happen to older people; over 2.1 million people under the age of 45 had high blood pressure in England in 2015. This means most of us don’t even realise we have it. That’s why it’s important to have regular medical examinations to make sure your blood pressure isn’t creeping up as you grow older.

Health policies dependent on antihypertensive drugs alone are only partially successful as many people with high blood pressure do not take medication, or take enough, to achieve control. Lifestyle modifications also play a part in management and prevention, with experts recommending a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, fish, low-fat dairy products – and low salt intake.

But how much salt is too much salt?

In 2018, our research team published an article reporting that having a healthy diet may not offset the effects of high salt intake on blood pressure, which captured the attention of social media globally.

I practice what I preach. I do not put additional salt in my food, and eat at least five portions of fruits and vegetables each day. The average intake of salt for the UK (data collected in 2014) was 8.0 g, so how hard is it to keep my salt intake to less than 6 g per day – that’s one and 1/4 teaspoon – as recommended by Public Health England and NICE guidelines? Can I do even better and match the ambitious WHO recommendation of 5 g per day (1 teaspoon)?

My daily salt intake

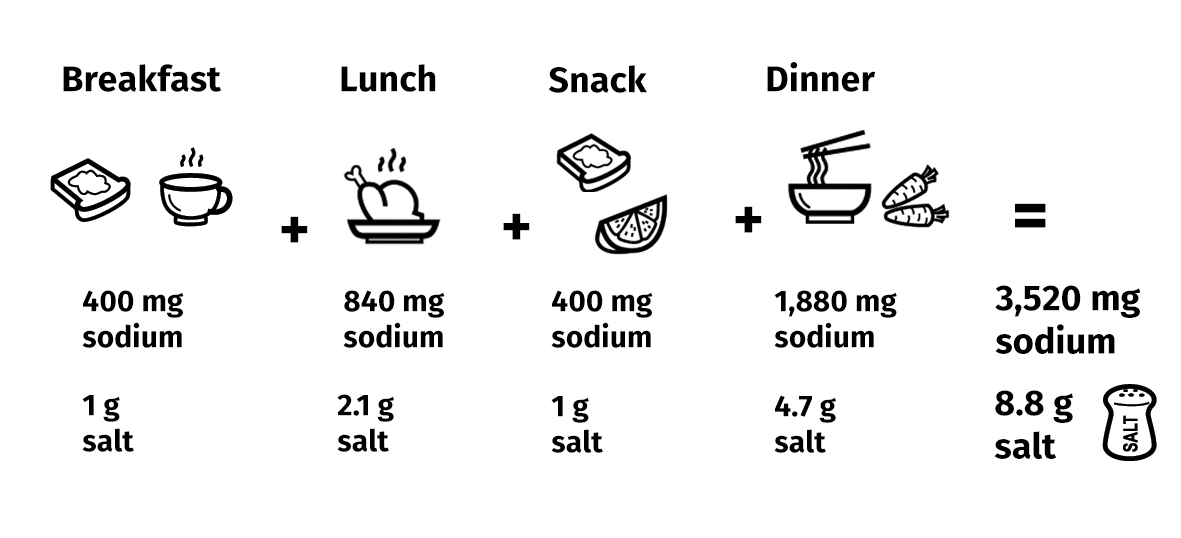

Before I left for work, I already had about 20% of my daily allowance, 400 mg of sodium that is 1 gram of salt!

- Breakfast: mug of coffee (0 salt) with 150 ml semi-skimmed milk (80 mg of sodium… naturally) and 2 slices of wholemeal bread (320 mg of sodium) with honey.

- Lunch: chicken salad (840 mg of sodium) and mango and lime (0).

- Snacks: wholegrain crispbread (400 mg of sodium = 1 g of salt) and clementine (0).

- Tea break: I had been busy so no tea and biscuit break today (FYI – UK’s favourite chocolate digestive has 80 mg sodium in each biscuit!)

- Dinner: spicy noodles (1,760 mg sodium = 4.4 g salt, noodles and the flavouring package) and lot of vegetables (120 mg sodium, natural)

According to food labels and nutrition tables, I have had 3,520 mg of sodium, that’s equal to 8.8 g of salt, so far; not having dressing on my salad and not slurping up all the soup in my noodles, my salt intake for today may just be 7 g, below the UK national average intake but way above the WHO recommendation of 5 g per day…and there’s still a few hours before bedtime!

Even as an informed professional, it is a challenge to maintain a low sodium intake as a large amount of the salt in our diet comes from processed food (e.g., cereals, bread, pizza, pasta, noodles). So it is important that food manufacturers take steps to reduce salt in their products and that we are smart consumers – know your food labels! You may see ‘sodium’ listed in food labels rather than salt; to convert sodium into salt, simply multiply the amount on the label by 0.0025.

Dr Queenie Chan (@QMYC1997) is a Senior Research Officer at the School of Public of Health. She is the co-Investigator of INTERMAP and her research has extensively on nutrition, examined the role of diet as it affects risk factors for cardio-pulmonary disease.

Great article! I’ve also been researching potassium intake an its hypotensive properties. I’m trying to better understand the salt-to-potassium ratio and whether this is also a useful (more? less?) useful predictor/correlation to blood pressure. Any extra info or direction to other sources would be nice!

Using INTERSALT data (52 populations from 32 countries), Iwahori et al suggested that urinary spot Na/K ratio could be a low burden monitoring tool for urinary sodium and potassium intake in populations. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw287

As for using Na/K ratio as personal monitoring, Iwahori et al had conducted a RCT see article doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20160144

very nice article, useful information.