22 February is World Encephalitis Day. Founded by The Encephalitis Society four years ago, it aims to help raise awareness of the disease on an international scale.

In a nutshell, encephalitis refers to the inflammation of the brain. Up until recently, it was thought that encephalitis was simply either a viral or bacterial infection. However, in 2005, research described a new version of the disease: auto-immune or ‘anti-NMDAR encephalitis’, which is caused by antibodies that attack the brain tissue. In all its forms, encephalitis is incredibly rare: herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE), for instance, affects approximately one in 1,000,000 children. Although there are clear treatment routes available, viral encephalitis is incredibly destructive. The virus can cause irreversible damage in the brain, which will continue to impact upon a patient’s quality of life well after their short-term recovery from the disease itself.

Despite its often devastating consequences, the rarity of encephalitis might raise some important questions for those hearing about the disease for the first time, namely: why should we spend our time researching something that affects so few people?

It’s crucial to acknowledge that just because something is rare, it doesn’t mean that it’s not important. I started working on herpes simplex encephalitis during my time as a postdoc, because it’s an incredibly useful paradigm for studying genetic disorders, and human genetics in general. Looking at cases of encephalitis can also tell us so much about human immune responses to infection. By investigating what has gone wrong in the body in these rare cases of encephalitis, we also learn more about which immune responses are essential to fighting diseases in the average person. Not only does our research into encephalitis allow us to better combat the disease itself, it also give us insights into the mechanisms at work in our body that help to protect the brain from infection and inflammation. We’re beginning to see that our findings have far-reaching implications for other neurological disorders that may be linked to encephalitis via a crossover of immune mechanisms.

With the relatively recent discovery of anti-NMDAR encephalitis, the field of autoimmune encephalitis has blossomed. Although my primary research is rooted in the viral, infectious type of the disease, we’re beginning to investigate its relationship to this newer form. I’m now working with Dr Ming Lim at the Evelina’s Children Hospital at King’s College London, and Dr Yael Hacohen at the Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health at UCL, to try and pinpoint whether there is a link between the two. More specifically, I’m interested in finding out if suffering from HSE means that a patient is more predisposed to developing autoimmune encephalitis further down the line.

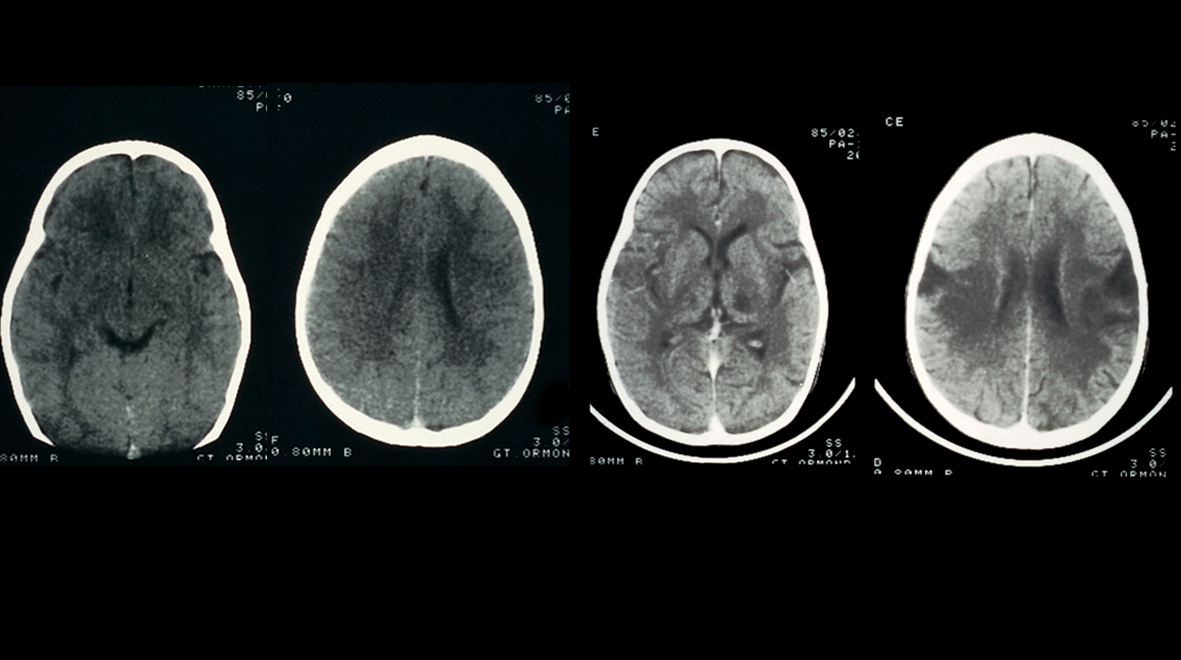

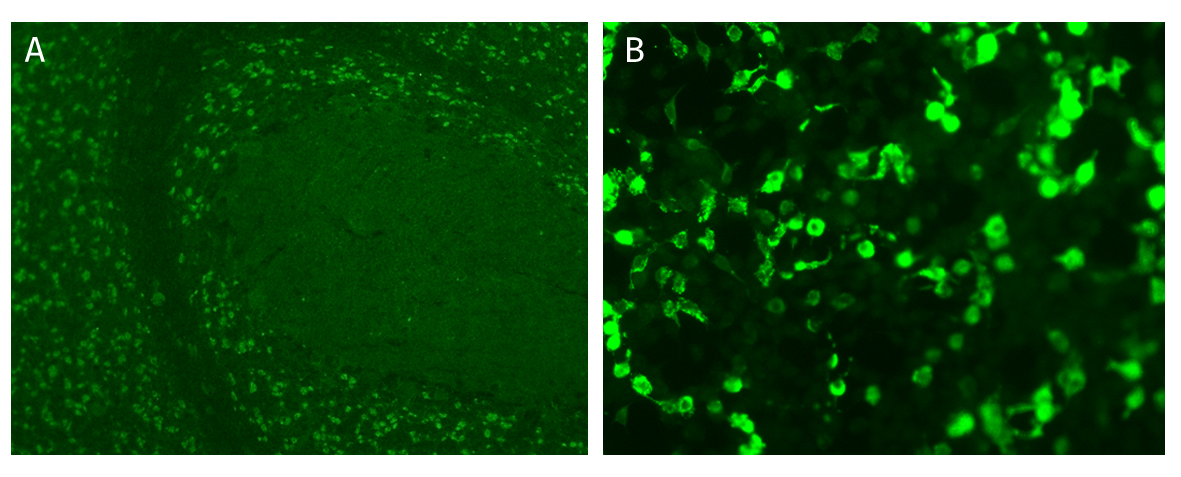

We’ve seen a few reports suggesting that this might be the case: we know that there are people who have been diagnosed with anti-NMDAR encephalitis who previously had HSE. In most cases, HSE patients are given Acyclovir – a very effective treatment that is taken over the course of 21 days. Typically, as the acute infection begins to clear from the body, things begin to improve. However, in a small proportion of cases, we see relapse: patients show signs of encephalitis again, usually within a year of the first episode. People used to just attribute this to the viral infection. However, when we look closely at the clinical notes in a subset of these cases, there is no evidence of any live virus despite clear inflammation in the brain. Positive indirect immunofluorescent staining of rat cerebellum tissue (A) and 293 cells expressing the NMDAR/NR1 protein(B) to detect anti-NMDAR antibodies in the serum of patients.

Positive indirect immunofluorescent staining of rat cerebellum tissue (A) and 293 cells expressing the NMDAR/NR1 protein(B) to detect anti-NMDAR antibodies in the serum of patients.

One of the key aims of my research is to understand the risk factors associated with encephalitis in all its forms: why is that one person should be predisposed to developing this life-threatening disease, and 999,999 others not? Does the reason exist in our genes? This is a particularly important question to ask in the context of looking at the relationship between these different forms of the disease. If it’s true that suffering from HSE might mean it’s more likely that you’ll develop anti-NMDAR, then at the very least this offers us another point of intervention. If we know this particular subset of patients are at-risk, we can try and halt the progression of the disease, or at a minimum catch what is happening within the body, as it happens.

The lack of available cases is the biggest roadblock to us doing this, and studying the disease in general. We now have a lot of retrospective data, which is helpful in establishing a hypothesis, but prospective recruitment would be ideal to confirm anything further. We need to be able to see how and when the autoimmune form of encephalitis begins to take effect in the body: for instance, when do antibodies begin developing? What causes these antibodies to develop? Is there an infectious trigger? These types of questions can begin to be answered through observations from our cohorts.

There is plenty of work left to do, and raising the profile of the disease through awareness incentives such as World Encephalitis Day has the potential to help us answer some of these pressing questions. By raising awareness, people suffering from encephalitis – and their family and friends – will have more of an inclination to learn about the disease and help with ongoing research. We have patient awareness groups that feed into our research, and are vital to helping us to better understand the disease and the way in which we treat it.

It’s important to reiterate that our current research into encephalitis won’t just improve our knowledge of the disease itself. In many ways, encephalitis tells us the story of how our immune system should work; how it should protect our brain from inflammation and infection, and keep us healthy. It therefore has far-reaching consequences for a range of other, related diseases.

Dr Vanessa Sancho-Shimizu is a Senior Research Fellow in the Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine. She is currently working on understanding the Mendelian predisposition to rare childhood infections specifically: identifying genes underlying childhood herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE), severe viral infections and invasive meningococcal disease (IMD).

Following the launch of the Faculty of Medicine’s reorganised academic structure on 1 August 2019, this post was recategorised to Department of Infectious Disease.

hi, Vanessa Sancho Shimizu,

very helpfull blog for medical student – Encephalitis: the rare disease with a million implications

Hi,

This is definitely very helpful blog. Here I want to notify that my mother who is 53 years old , is also suffering from Viral Encephalitis. She was diagnosed from this disease in May, 2014.

Since then i resigned from my job to be her caregiver .

I want more information about this , more importantly about the post effects and treatment to make her getting back to her normal life.