Tucked away in Charing Cross Hospital is Imperial’s best-kept secret: The Pathology Museum. Housing a 2,500-strong collection of anatomical specimens, the Pathology Museum contains some rare and unique artefacts dating from 1888, including the first hysterectomy performed in England.

Carefully curated by the Human Anatomy Unit (HAU), the specimens are grouped together based on organ systems, creating a well-arranged display of human pathology. The museum’s primary function is to help educate medical and biomedical students to diagnose diseases. The museum also hosts a number of conference and short courses in pathology for experienced professionals.

The collection incorporates specimens from across the Faculty of Medicine’s founding medical schools, there are an astonishing 4,000 further specimens not on display. This vast archive provides a snapshot of the historical foundations of the medical school.As medical teaching has changed over the years, this has presented challenges for the role of the pathology museums in medical education. Today, traditional teaching methods in  the museum are complemented with the latest learning technology, such as an Anatomage Table which displays life-sized 3D images of full body anatomy. The museum staff are going through the task of digitising the old catalogue to create a new database.

the museum are complemented with the latest learning technology, such as an Anatomage Table which displays life-sized 3D images of full body anatomy. The museum staff are going through the task of digitising the old catalogue to create a new database.

Margaret Bennett, the Pathology Museum Officer joined the HAU last year to support with these activities and help conserve the collection. For National Pathology Week, Margaret shares her top six specimens.

Guinea worm

The guinea worm (Dracunculus medinensis) is a parasite that can infect humans with guinea worm disease after drinking contaminated water. Only females carry the disease, and at up to 800mm long, they are one of the longest nematodes. Males are much shorter at 12-29mm long.

To extract the worm, a person must wrap the live worm around a piece of sterile gauze or a stick – as seen in this specimen. The process can be long, taking anywhere from hours to a week. This is a similar treatment noted in the famous ancient Egyptian medical text, the Ebers papyrus from 1550 BC.

There is a theory that the Rod of Asclepius – the symbol which represents medical practice – could be interpreted as a guinea worm wrapped around a rod. According to this theory, physicians might have advertised this common service by posting a sign depicting a worm on a rod. However plausible, there is no firm evidence in support of this.

The container for this specimen is one of the few glass jars that we have in the museum and requires a different set of conservation techniques than the modern acrylic containers that most specimens are displayed in. The jar is blown as one piece with no joints or seams. The specimen is then suspended with silk thread and a glass disc sealed on to the top. While the sealant used is a modern approximation of the traditional bitumen, many of the techniques used in the process haven’t changed in hundreds of years.

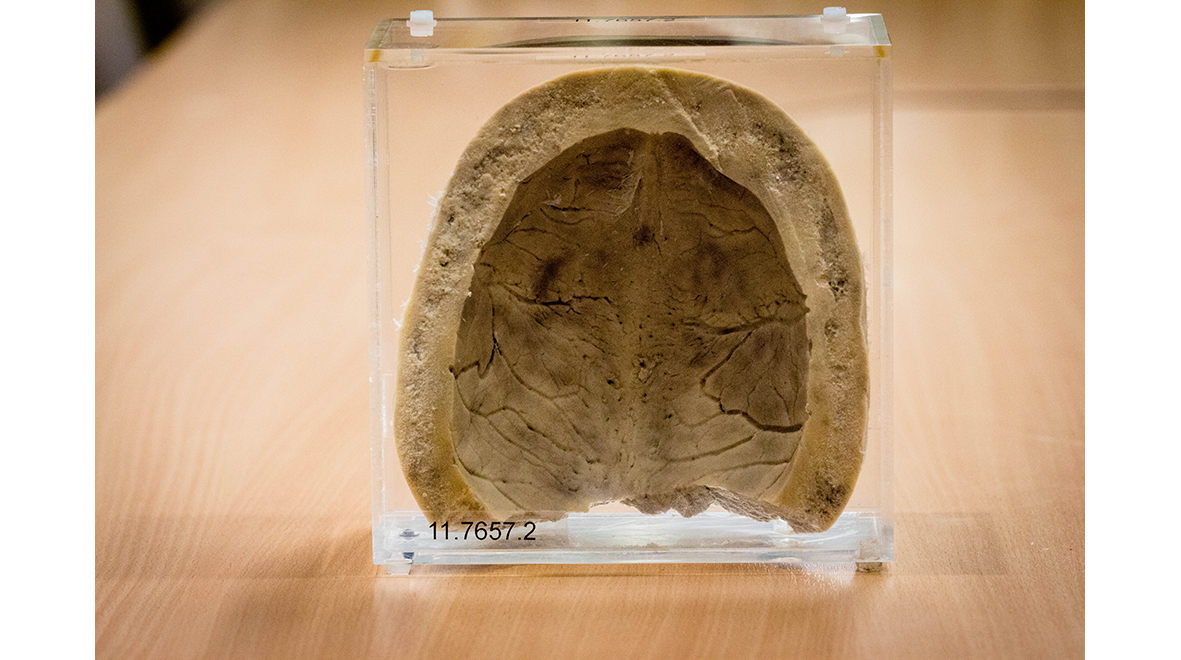

Paget’s disease

Paget’s disease of bone is a condition caused by the excessive breakdown and formation of bone, followed by disorganised bone remodelling. This causes affected bones to weaken, resulting in pain, misshapen bones, fractures and arthritis in the joints near the affected bones.

In this specimen, we can see the disorganised excessive bone growth in the thickness of the skull. I first saw this condition, which has existed for centuries, while working and studying as an archaeologist. It is remarkable that while modern medicine has cured many diseases and infections, there are still some pathologies that have changed very little.

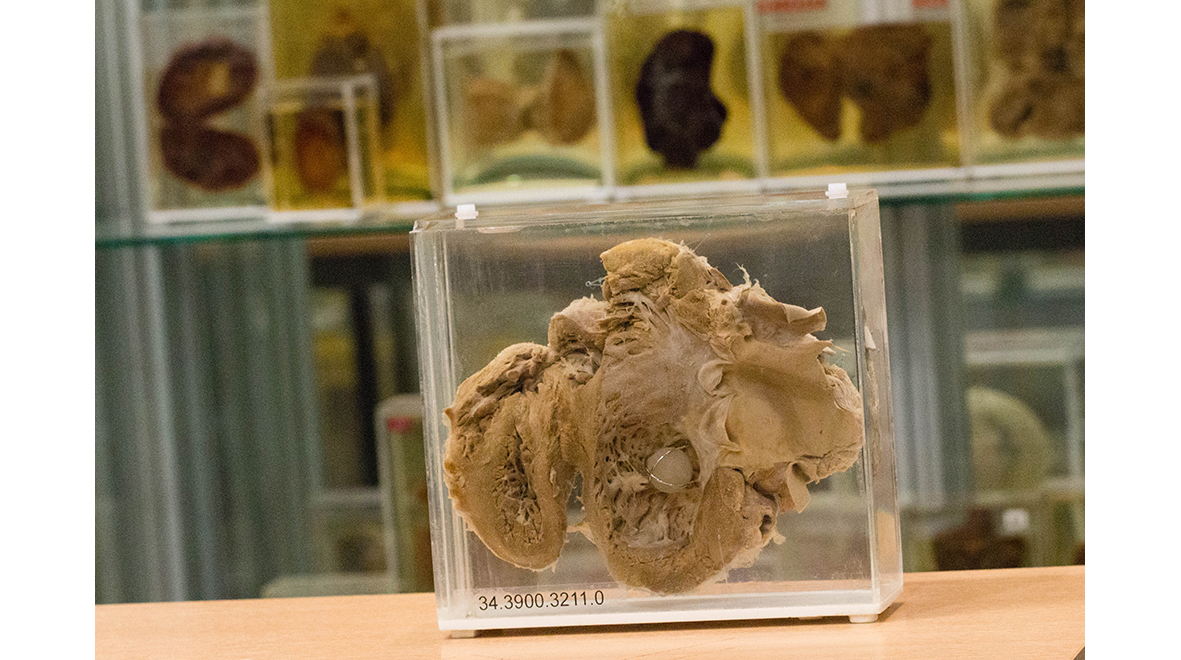

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), the second-most common cause of death from infectious disease, is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It is spread when a person who has active TB in their lungs transmits the bacteria to another person through the air. The classic symptoms of active TB are a chronic cough with blood-containing sputum, fever, night sweats, and weight loss.

Tuberculosis was for centuries associated with poetic and artistic qualities among those infected. Major artistic figures such as the poet John Keats, the composer Frederic Chopin and the novelist Charlotte Brontë died from the disease.

In this specimen, we can see the cavities in the lungs caused by the infection. These are called granulomas and are caused by the body’s immune trying to fight the mycobacterium. Current research is looking to map the genome of the mycobacterium that causes the infection in the hope that it will lead to a cure.

Trichobezoar (Hairball)

A trichobezoar, more commonly known as a hairball, is a type of bezoar – a mass found trapped in the gastrointestinal system – formed from the ingestion of hair. Trichobezoars are often associated with compulsive hair pulling. They are rare, but can be fatal if undetected and surgical intervention is often required.

In this specimen the hairball has become so large that it has started to take on the shape of the stomach!

Heart valve replacement

An artificial heart valve is a device implanted in the heart of a patient with valvular heart disease – a disease involving one or more of the four valves of the heart. When one of heart valves malfunctions, the medical choice may be to replace the natural valve with an artificial valve through open-heart surgery.

This specimen shows a type of valve called a ball and cage implantation. The students that visit and use the museum find this specimen particularly fascinating, I think, because it enables them to see a surgical procedure that they may one day carry out themselves.

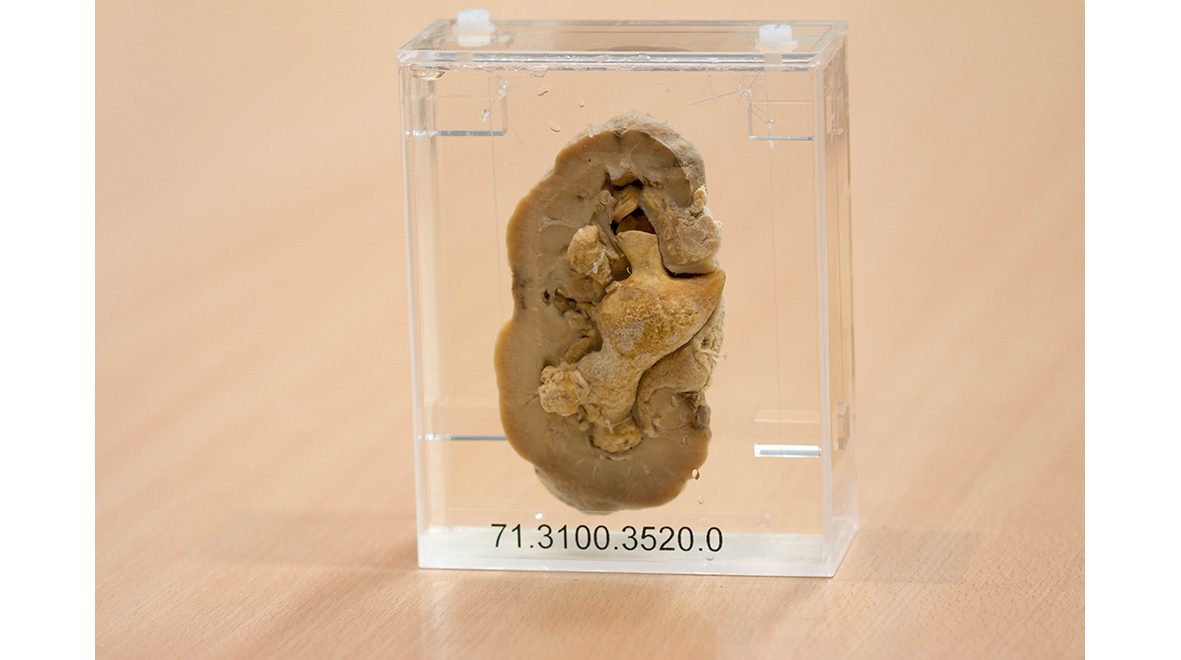

Staghorn kidney stone

A staghorn kidney stone is a term used to describe a large stone that takes up more than one branch of the collecting system in the renal pelvis of the kidney. Some of the risk factors for staghorn stone formation include a long-standing history of stones, certain unique metabolic defects, and repeated urinary tract infections with particular types of bacteria. If a staghorn stone occurs in association with infection, there may be a pattern of intermittent and recurrent infection which may persist until the staghorn stone is removed.

In this specimen, we can see that the stone has filled several branches resulting in the characteristic antler shape. While many people may suffer from kidney stones during their life it is rare to develop staghorn stones, especially as pronounced as the one shown here.

These six specimens are only a handful of the fascinating items that I have the privilege of maintaining every day. Pathology and anatomy museums have existed since the earliest days of medical study and hopefully, with careful conservation, they will continue to enrich the education of students and professionals for many years to come.

Margaret Bennett is the Pathology Museum Officer based in the Human Anatomy Unit at Imperial College London, Charing Cross Campus.

prof premraj pushpakaran writes — let us celebrate International Pathology Day!!!

Is the museum open to the public? My daughter is doing an anatomy project for art gcse. Thanks

Hi Lucy. I’m afraid the museum is only open to Imperial medical students and researchers. We can recommend the Horniman Museum for anatomical and pathological displays or the Grant Museum of Zoology.