Learning Connections 2019: Spaces, People, Practice

Luke McCrone, PhD student

I attended the Learning Connections 2019: Spaces, People, Practice conference held on 5-6 December 2019 in University College Cork (UCC), Ireland.

The conference set out to answer two central questions:

- How can we connect across disciplinary boundaries, and break down barriers between academia, administration, community and industry to strive for optimal student learning in Third Level Institutions?

- How can learning in different spaces– physical, active, virtual, off campus, enable all students, as global citizens, to think through and solve big problems?

These questions translated into six conference themes within which conference attendees submitted peer-reviewed digests that summarised lightning talks or concise paper presentations:

- Learning space design

- Learning beyond the classroom: community & industry partnerships

- Inclusive and accessible learning and teaching

- Active learning: classrooms, makerspaces, studio spaces

- Learning in a virtual space

- Innovative methodologies for research-led education

I submitted a concise paper titled ‘Transitional space: learning in the spaces in-between’ which fell under the active learning theme above (theme 4). This paper linked many of my key PhD findings to this theme, and in so doing made a case for the need to consider transition between learning spaces (physical, temporal, cognitive) when implementing and designing for active forms of learning. The spaces that constitute active learning are integral, but the transition between these spaces mediates their connection. This transition operates at different levels, from a student entering or exiting a timetabled lecture, to a student redirecting attention from a lecture to their mobile phone. Transition between these different learning spaces provides opportunity for exchange and interaction that is observably important for learning.

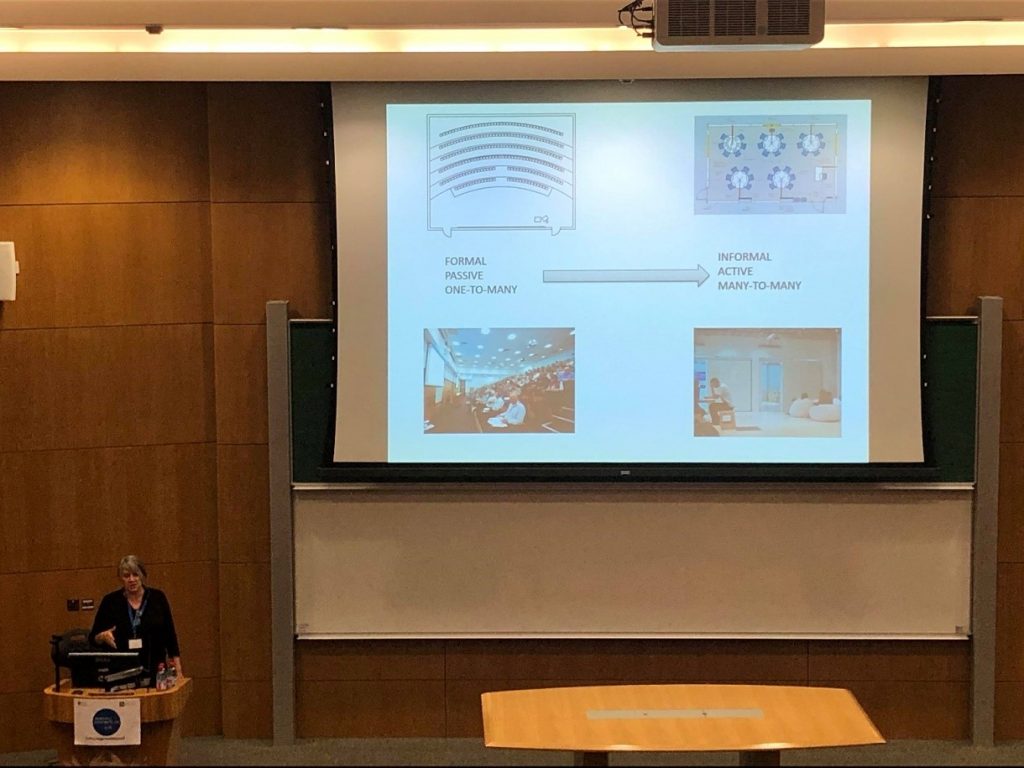

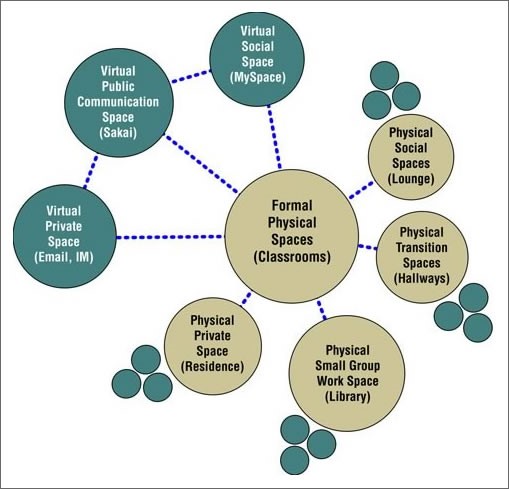

The premise of my paper was concomitant with work presented by the keynote speaker Dr Jos Boys who emphasised the need to think beyond the binary framing of informal and formal learning and to begin considering learning as an interconnected assemblage (see figure). Jos’ background in architecture meant that she alluded to the implications of this thinking for space design and the institutional governance of processes that inform this design. I was very reassured to learn of Jos’ positive experience with projects involving students as active participants in (re-)designing informal learning spaces, given similar recent work at Imperial under the StudentShapers scheme. Jos’ argument was an important one: student active participation should not be limited to classroom learning, but should extend to their active involvement in the creation of spaces that facilitate that learning.

Highlights

In addition to the keynote presentation, I found a guided tour around UCC’s Student Hub particularly useful. This recently built complex consists of a series of next generation teaching spaces and collaborative connecting spaces. The Hub possesses no disciplinary signature helping to break down disciplinary boundaries and provide inclusive space. Many of the Hub’s spaces communicate flexibility and openness, including the atrium-style space in the photo, such that users can use them in a variety of ways and take full ownership; the literature indicates this makes spaces more ‘sticky’ and improves user experience. The hub will be open from January 2020 to members of UCC.

I found a separate session titled ‘Common Room’ similarly fruitful, led by three individuals, one of which was a colleague Dr Brent Carnell from UCL. Brent made a case for the importance of ‘in-between’ spaces where students congregate and move in transit across campus. Physically speaking, this aspect of the presentation shared similarity with transitional space and was therefore a useful affirmation of my recent thinking. However, I felt it missed a deep understanding of why these sorts of spaces are educationally beneficial, an area that remains poorly developed in the literature. Using UCL as an example, the workshop more generally made me reflect on how to cultivate community on a disparate campus.

Implications

As is the case with pedagogic research, it is reassuring to see a shift in thinking from designing for teaching and transmission of knowledge to designing for active learning. Changes to curriculum, pedagogy and technology naturally mean that this learning now extends beyond the classroom space. This warrants a change in architectural approach, including the incorporation of immediate transitional spaces that support interactions pre- and post-lecture.

I welcome thoughts and questions on this article so please feel free get in touch via email.