The scientific iceberg

Sophie Rutschmann, Senior Lecturer, Department of Medicine

This time last year, I was in the midst of my first educational research project. As a student on the MEd ULT, I had completed my ethical approval, was finishing my interviews and transcribing them. I remember thinking that this was the tricky part, but I now know it was just the tedious one. Analysing the data, doing justice to the personal experience my participants had openly shared with me, and importantly trying to answer my research question in the least unbiased way were the challenges yet to come. I later also realised that, had I read more of the relevant literature before, I could have written sharper interview questions or picked a much narrower topic to investigate. In hindsight, I was merely re-discovering the struggles inherently associated with research, just in a new field. But by that stage, not too much could be done, so I ploughed on.

So what?

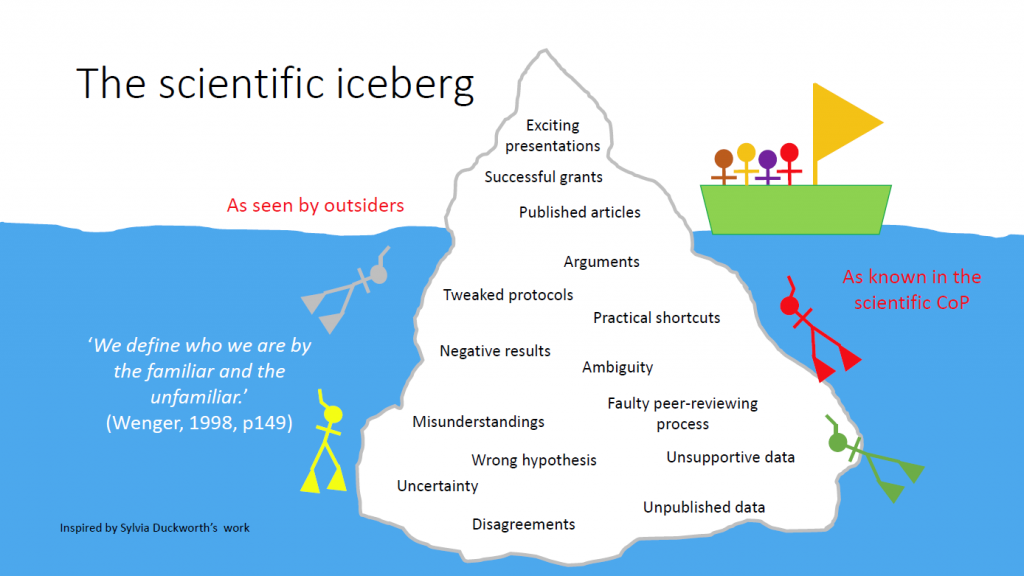

So what was this ‘broad-but-close-to-my-heart’ research project about? Since focussing my career on education, I have been exploring ways to bring our daily professional activities into the classroom. Why? Because I profoundly believe that there is no better way to learn than on the job: there must after all be a reason we all became good critical scientists without having had a single specific critical thinking class! My everlasting quest has therefore been to identify educational events from our everyday professional lives and reproduce them in the classroom. Some of these activities, like chatting around a coffee and ‘exchanging ideas’ will come naturally to our students! Some, like giving them the opportunity to freely use the scientific method by designing and executing their own mini-research project in our teaching labs, requires more planning. Some will also need careful preparation, such as allowing students to discover the hidden side of science, to realise that old-timers (that’s us!) can be challenged and can be wrong (hopefully not all the time!), and that science is full of controversies – something we do not talk about enough in the classroom but which, according to the PhD participants in my MEd project, is truly transformational in terms of critical thinking. This idea of a hidden but transformative side to science, that I called the ‘scientific iceberg’ (see illustration below), was recently presented at the Advance HE STEM conference in Birmingham, a presentation followed by some thoughtful discussions with peers from other HE institutions.

What next?

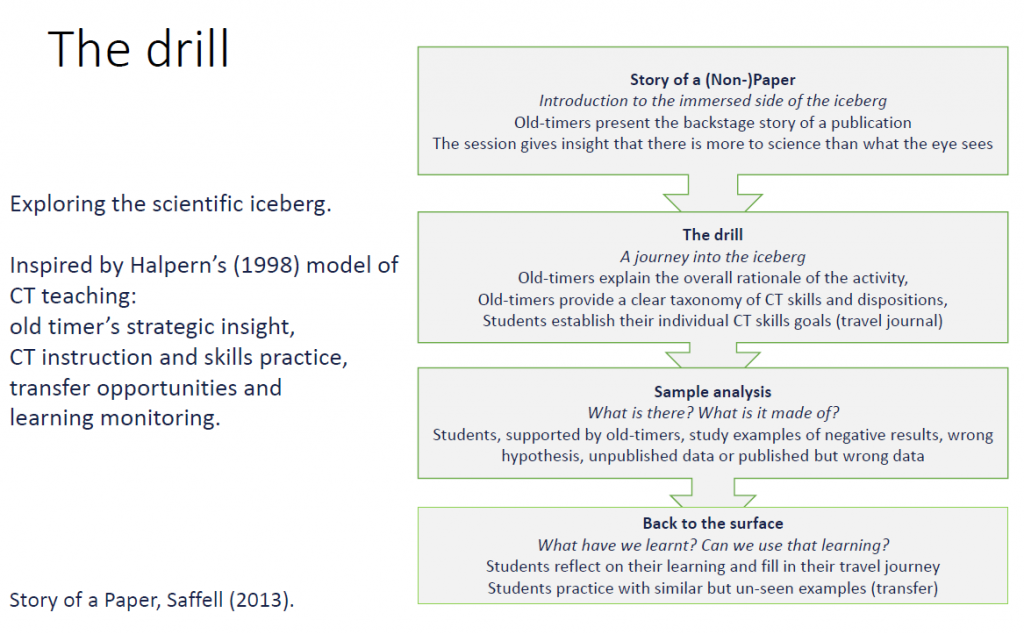

With a recently reviewed curriculum and based on the results of my MEd project, I have the incredible opportunity to take the next cohort of MSc Immunology students on a journey to explore the immersed part of the iceberg – to ‘drill’ and see with them what can be found in the carrot. Adapting Halpern’s model of teaching critical thinking to this idea of scientific iceberg, I have designed a series of activities which will hopefully help my students (and others?) develop their critical thinking skills further.

So I’m now back to square one: applying for ethical approval to not only evaluate the impact of this activity but also research whether the drill, directly inspired by the experience of newcomers in our community, has a positive impact even without the time, or trial and error factors we all know are key to learning on the job. So hopefully more to write about in another year’s time!