New blog address

The Climate and Environment at Imperial blog has moved. Visit our new blog.

The Climate and Environment at Imperial blog has moved. Visit our new blog.

by Alyssa Gilbert, Head of Policy and Translation, Grantham Institute

It is just like some colossally awful house-bidding process. Only here it is not just an attractive three-bed semi-detached residence that is at stake. In the run up to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Conference in Paris in December, each country is submitting its bargaining chip, a so-called Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC).

It is just like some colossally awful house-bidding process. Only here it is not just an attractive three-bed semi-detached residence that is at stake. In the run up to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Conference in Paris in December, each country is submitting its bargaining chip, a so-called Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC).

The levels that countries put forward is part of the complex international climate negotiations – countries are keen to show genuine commitments to climate change action, but very few are willing to rush ahead of other nations. It is a classical prisoner’s dilemma.

Analysts and, quite frankly, those who care about climate change are waiting with bated breath to see what these commitments will add up to. Once each country has stated what it will do, how close will we be to the target of limiting global temperature rise to 2°C?

Announcements of INDCs are coming thick and fast, albeit months after the purported deadline. Last week saw a bumper crop of INDCs from Iceland, Serbia, South Korea and the long-anticipated Chinese contribution. These contributions bump us up to over 55% coverage of current global emissions, and 43% of countries.

So, the good news is, we are starting to see some commitments, but where does this take us? A good step-by-step update, complete with lovely infographic is regularly updated on The Carbon Brief .

The expert analysts at the Climate Action Tracker weigh up each of the INDCs to see what that means for the climate as a whole, and it is not looking good. The majority of countries assessed have commitments, and matching national policies, that fall within the ‘medium’ range – this means that they will not keep us within the 2°C limit.

Looking more specifically at last week’s key announcements, different national approaches give us a flavour of some of the key issues up for debate – the use of markets, the need for effective national policies and the potential and desire to overachieve.

Firstly the markets/no-markets debate. South Korea’s INDC is deemed inadequate by the Climate Action Tracker because it just doesn’t demand steep enough cuts to reduce our carbon envelope. In addition, the challenge of kick-starting a step-change in domestic emissions in this well-developed country will be exacerbated by a heavy reliance on international market-mechanisms, i.e. buying reductions achieved in other countries. Critics of this approach reveal a duality – on the one hand the use of more markets is lauded because it can bring down the global costs of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, whilst on the other hand, countries can use international markets as a way to avoid action at home.

The verdict on China has revealed a second interesting theme, emphasising that action through national policies is needed to make the INDCs effective. In fact, the Climate Action Tracker notes that China’s national policies fare much better than the overall carbon intensity target – which is a good sign, even if the overall trajectory still only scores a medium. A useful English translation of the China National Center for Climate Change Strategy and International Cooperation (NCSC)’s analysis of the INDC can be found here. This analysis emphasises some of the development, greenhouse gas monitoring (MRV) and other challenges that China will still face in delivering on its INDCs.

The importance of national policies should hit home here in the UK. In the same week as China released its INDCs, the UK’s Climate change Committee (CCC) noted that we are doing well, but not well enough (see report). In the end the INDCs need to translate to solid, effective actions within each individual country. And doing so successfully is far from easy.

For me, the third take home message is, as ever, political. It has been widely reported that the China’s overall INDC target is deliberately loose, to allow for overachievement. Let’s hope other countries rise to the competitive challenge – a race to overachieve would be a great way to try and beat the mediocrity of the current INDC commitments and ensure we meet the necessary level of ambition over the coming years.

Let’s all take a leaf out of China’s book – their INDC represents a challenging trajectory, but they are moving fast…..

The current analysis on the table provides information about just how hard it will be for countries to steer towards their stated goals. I will be a more frequent presence on the blogosphere from now on, pulling together my thoughts on climate change commitment and actions at all levels of government, and in business, in the run up to Paris but also, and more importantly, beyond!

Follow Alyssa on Twitter: @AlyssaRGilbert

by Dr Kris Murray, Grantham Lecturer in Global Change Ecology

Today the Lancet Commission on Health and Climate announced the release of their new report “2015 Lancet Commission on Health and Climate Change: Policy Responses to Protect Public Health”.

Today the Lancet Commission on Health and Climate announced the release of their new report “2015 Lancet Commission on Health and Climate Change: Policy Responses to Protect Public Health”.

Following a first report released in 2009, which concluded that “Climate change is the biggest global health threat of the 21st century”, today’s report has a proactive, positive take-home: “tackling climate change could be the greatest global health opportunity of the 21st century.”

Strategically released following the 68th World Health Assembly held last month and in the lead up to the UNFCCC’s COP21, to be held in Paris later this year, the report is the culmination of a second international (predominantly Chinese-European) working group assembled to assess the health impacts of climate change and to identify and accelerate effective mitigation and adaptation policies over the next 5 years.

The report provides 9 recommendations and delivers 1 promise:

Accompanying the launch of the report, the Lancet Commission on Health and Climate are holding a number of events around the world (including London, New York and Canberra), which will include speakers, panel discussions and an opportunity for Q&A from participants. The Health and Environment Alliance will also host a virtual launch event.

While the recommendations are not exactly breaking radical new ground, they do represent a welcome synthesis of the front-line evidence on the health impacts of climate change with a clear focus on solutions (the details of which make up the bulk of the report).

Perhaps more critically, they also crank up the volume of the voice of the health community at a critical time in the climate change arena – a voice that has a formidable track record of achievement in confronting other highly complex, trans-national, politically charged threats to health.

For further comment on the report, see the Lancet website.

By Clea Kolster, PhD student, Science and Solutions for a Changing Planet

The term ‘sustainable development’ was first coined in 1987 in the UN’s World Commission on Environment and Development report, Our Common Future. Almost 30 years later, the concept of sustainable development is more relevant than ever.

The definition given in the report is, to this date, the most widely accepted modern definition of the term: ‘Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.’ Climate and society, energy, water, ecosystem health and monitoring, global health, poverty, urbanization, natural disasters, food, ecology and nutrition – these are some of the main problems that need to be tackled when discussing the possibility of sustainable development. They are all complex problems that require an interdisciplinary and analytical approach. Earlier this year, I joined a group of people doing just that.

On Friday April 3rd 2015, I entered the land of Ivy League elites of Columbia University to take part in the 5th Annual Interdisciplinary PhD Workshop on Sustainable Development. Having been on a year abroad at Columbia University during my undergraduate degree, I knew the spot pretty well and was thrilled about getting the chance to come back as a matured and informed PhD student ready and eager to present my work.

Arriving at the workshop, I struck up a conversation with some of the students around me. I quickly understood that a number of us had made the cross-Atlantic trip, with participants from Denmark, Italy, Sweden, France and even Australia. Students also came from Canada and Mexico, with a large majority attending world-renowned US universities, including Harvard, MIT, Yale, Princeton, UC Berkeley and of course Columbia.

The highlight of the first day was a keynote speech by American economist Jeffrey Sachs, head of the Earth Institute at Columbia University., Sachs has an incredible track record: he is a Quetelet professor (honorary distinction given to Columbia University professors, awarded to only four professors since 1963) of Sustainable Development, special advisor to Ban Ki-Moon, youngest economics professor at Harvard University (age 28), author of three New York Times bestsellers – and the list goes on.

One of the things that engrossed me most was his emphasis on planetary boundaries and the current ideological conflict between growth (mostly economic) and environmental sustainability. Sachs definitely got the whole room thinking about whether or not sustainable development is actually feasible and, for those like myself who desperately want that answer to be positive, what one can do to bring us closer to that goal: a world with sustainable economic, social and environmental objectives.

The rest of the afternoon featured sessions on a variety of topics from natural disasters – including the Venetian example of floods – to urban planning in China and development in India. After a long afternoon of presentations, I got the chance to network and socialize with the students. I met some very interesting individuals, most of whom, contrary to myself, feel as though they are economists before anything else, in spite of an earlier education in engineering.

On the second day, I was due to give my presentation as part of the Energy. In a small room filled with 10-15 other PhD students, all of whom were senior to me, and a few professors, I sat nervously waiting for my turn, beginning to realize that my presentation was clearly going to be one of the most “engineeringy” and technical of all.

I finally gave my 20 minute talk on the “Techno-Economic Analysis of the Link between Above Ground CO2 Capture, Transport, Usage for Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) and Storage”. I was happy to take some interesting questions at the end of it (which I hoped meant that the audience was actually interested by my topic) and later on at the coffee reception engaged in some stimulating discussions with some of my peers. It was clear that in spite of our dissimilar approaches, we had all contributed to responding to the question of sustainable development and its feasibility.

Did you know that 1.4 billion people currently live in a state of extreme poverty at below $1.25/day? In fact, it will take a 4 to 5 time increase in total global output by 2050 to get poor countries to meet the $40,000 per capita income of rich countries today. With figures like these, it isn’t surprising that large groups of individuals around the world dedicate their time to assessing and analyzing the best ways of achieving sustainable development encompassing economic, social and environmental goals.

In my view, sustainable development is feasible, we can tackle climate change, we can reduce our exploitation of natural capital while promoting economic growth, we can bridge the gap between poor and rich countries; the problem is – as Jeff Sachs pointed out – a lack of trust. A lack of trust leads to social and political instability and these will always impede sustainable development around the world.

References

World Commission on Environment and Development – Bruntland Commission. 1987. Our Common Future. s.l. : Oxford University Press, 1987.

Find out more about Clea’s research

Professor Jo Haigh, Co-director of the Grantham Institute reports back from the Climate Parliament meeting in Lucerne, 12 June 2015.

I have just found a seat on the train from Lucerne to Zurich airport. It is absolutely packed, I suppose, with people going away for the weekend. Staring through the window at the snow-capped mountains, and having spent the day at an inspirational conference set by the beautiful lake, I am wondering quite why anyone would want to leave.

I have just found a seat on the train from Lucerne to Zurich airport. It is absolutely packed, I suppose, with people going away for the weekend. Staring through the window at the snow-capped mountains, and having spent the day at an inspirational conference set by the beautiful lake, I am wondering quite why anyone would want to leave.

I have been at a meeting of the Climate Parliament. I only learned of this organisation recently but it is rather splendid – a group of legislators from across the world who are concerned about climate change and looking to influence governments to act. Seventy attendees came together to discuss the potential for a Global Energy Internet: an international electricity grid based on regional renewable energy sources.

Attendees were diverse – including MPs from four continents, industrialists, academics and representatives from energy and climate agencies. Simultaneous translation was provided between French, Spanish, Chinese and English, although that can’t have covered all the first languages represented. Fortunately my talk was first up so I could then concentrate on the rest.

For me a highlight was Li Junfeng, Director General of the Chinese National Centre for Climate Change Strategy and International Cooperation, who spoke on China’s energy demands, provision and ambitions for decarbonisation. He spoke of a “solar Silk Road for the 21st century” and noted the need for revolutions in energy production and for technical innovation with international cooperation on R&D in renewables: “Helping China is helping the World” he said.

Lei Xianzhang, of the State Grid Corporation of China, was up next discussing some of the technical issues and describing the construction of new wind and solar plants (grown by factors of 37 and 350 respectively since 2006) as well as very long (thousands of kilometres) high voltage DC transmission cables.

The political and technical challenges which have faced attempts to construct an energy grid across the Middle East and North Africa were elaborated by Tareq Emtairah, Director of the Centre for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency in Cairo. In the absence of an electricity market there has been very little exchange coordinated to date, but the delegates from Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia remained upbeat.

The political and technical challenges which have faced attempts to construct an energy grid across the Middle East and North Africa were elaborated by Tareq Emtairah, Director of the Centre for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency in Cairo. In the absence of an electricity market there has been very little exchange coordinated to date, but the delegates from Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia remained upbeat.

National energy security concerns were foremost in the minds of colleagues from Senegal and Peru. Efforts to connect to international grids were seen as a second priority. I could see their point, but perhaps they were reassured that the proposed networks could be established to the advantage of all.

Damien Ernst, an energy economist from the University of Liège, delivered an inspirational message: his calculations suggest that large scale facilities of solar and wind energy, with long transnational interconnections can provide energy cheaper than fossil fuels. Construct the grid first, he declares, and the incentive to develop renewables will follow.

It is a shame I have to miss tomorrow’s discussions, which will focus on finances and start to develop an action plan, but I have to attend my father’s 90th birthday party. If I live to 90, or 80, or even 75(?) perhaps I will see established an international energy internet. It is a fantastic vision.

By Dr Flora Whitmarsh, Grantham Institute

Although both Labour and the Liberal Democrats have pledged to decarbonise the electricity sector by 2030, climate change is unlikely to be a key issue in the run up to the May general election. This reflects a long term decline in political engagement with the problem since the Copenhagen conference in 2009. Although Copenhagen was held in the immediate wake of the global financial crisis, the ongoing recession and drop in living standards have shifted priorities away from tackling climate change. The increasing cost of energy might also have hardened attitudes towards green policies.

Although both Labour and the Liberal Democrats have pledged to decarbonise the electricity sector by 2030, climate change is unlikely to be a key issue in the run up to the May general election. This reflects a long term decline in political engagement with the problem since the Copenhagen conference in 2009. Although Copenhagen was held in the immediate wake of the global financial crisis, the ongoing recession and drop in living standards have shifted priorities away from tackling climate change. The increasing cost of energy might also have hardened attitudes towards green policies.

However, John Ashton, an independent speaker, commentator and adviser who served as the UK’s Special Representative for Climate Change from 2006 to 2012 says, “Acting on climate change is part of the solution to that problem.

“If you want to make the economy less vulnerable to external shocks, if you want to create new drivers for innovation, improve our infrastructure, deal with the terrible problem of cold homes and vulnerable people dying because of cold in the winter, all of those things; a very serious effort to build a low carbon economy will help with that.”

According to Ashton, the current generation of politicians hasn’t “engaged politically with climate change, which is quite a serious criticism. They have treated it as a policy issue; and there’s an enormous difference between politics and policy.

“Policy is about what you do. Given the sense of identity you have as a political movement, a political party, the values you have, the story you have about our country and where it’s going. Given all of that, what are you going to do?

“Politics is not primarily about policy. It is about who we are not what we want to do. It is about the sense of identity itself, the values, the history, the core national story, and how you talk to the country about what all this means for how we feel about ourselves.

“None of the mainstream political parties have done that. Moreover they haven’t understood the systemic nature of the climate problem. You can’t have one set of policies in a silo marked, if you like, ‘energy and climate policies’, and other conflicting policies in a silo called ‘macroeconomic policies’. Climate change is about the energy system, which is at the foundation of the economy. Changing the energy system means changing the growth model, and therefore intervening structurally using macroeconomic tools.”

In recent decades, the traditional differences between the parties have been eroded by the widespread adoption of the neoliberal prospectus, within a framework of neoclassical economics. Ashton says,

“All of the parties have core stories that have been heavily degraded by the sterile doctrines of neoliberalism and the consumer society. So they don’t talk to us very much about who we are, and where we came from, and where we’re going.”

According to Ashton, this state of affairs has precipitated “a collapse of confidence in politics itself, which we’ll see in the election, reflected by the fact that the vote for the major parties will probably be lower than it’s ever been in my lifetime.” The proportion of the vote going to Labour and the Conservatives collectively was 65.9% in 2005 and 67.6% in 2010, down from over 90% in the 1950s.

Ashton continued, “This isn’t a problem of dysfunctional climate politics; it’s a problem of dysfunctional politics. Climate change is not the only thing that we’re not talking about that we would be talking about if we had functional politics.

“Take a different example. A generation ago, Hitler and what he stood for were still fresh in people’s minds. The core political story in Britain and across much of Europe revolved more than it does now around human universality and the need to make sure that the strong look after the weak and vulnerable. We would not then have turned our backs, as we are doing now, on the plight of the refugees drowning every day in the attempt to cross the Mediterranean. Nowadays our leaders still claim the same values but they do not act accordingly. Of course, expediency and narrow self-interest have always to some extent got in the way of moral coherence. But the gap today is wider than it has been for a long time and people sense that.

“Of course climate change is also a question of justice and solidarity, and some of the refugees are being displaced at least partly by what look like climatic stresses. So the Mediterranean example is not entirely separate.

“If we want to bring about the political renewal we need, we must all do more to connect ‘what we want to do’ to ‘who we are’. Those who aspire to lead us particularly need to focus on this. Building a real political conversation about climate change will have to play a part in that.

“If you want to reconnect politics to reality, to the reality that people experience, then climate change is a good thing to talk about. But they [British politicians] haven’t found the language, and there’s no time now, between now and the election, to construct the right language for that.”

So, what can be done to get climate change back onto the political agenda more generally? According to Ashton, the answer doesn’t lie solely in the hands of politicians. Scientists have a key role to play in communicating the implications of climate change.

“You need to have much better communication taking place between the world of knowledge, if you like, science, the place where the Grantham Institute has its roots, and the world of choice which is politics, because these have to be political choices informed by science”, says Ashton,

“I think a challenge for the Grantham Institute is to act as a kind of catalyst and stimulant for the rapid upgrade in the skills we need among scientists to get stuck into that challenge.”

Read our joint policy brief on Climate change priorities for the next UK government

This blog post is part of a series on Responding to Environmental Change event, organised by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) funded Doctoral Training Partnerships at Imperial (SSCP), and the University of Reading and the University of Surrey (SCENARIO).

A recent event in London brought together emerging environmental scientists (PhD students and early career researchers) with leaders from business, policy and academia to explore the challenges posed by environmental change and opportunities to work in collaboration to respond to these.

Communities today find themselves and the environments they live in under increasing pressure. This is driven by growing populations, urban expansion and improving living standards that place increasing stress on natural resources. Added to this is the rising threat from environmental hazards and environmental change.

Research, development and innovation within the environmental sciences and beyond offers the opportunity to manage these pressures and risks, exploring how we can live sustainably with environmental change, whatever its drivers.

Discussion at the event covered three key societal challenges and their implications for business and policy. A summary of these talks has been captured by students attending the event and can be found below.

The event was organised by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) funded Doctoral Training Partnerships at Imperial (SSCP), and the University of Reading and the University of Surrey (SCENARIO).

Natural resources are fundamental for wellbeing, economic growth and sustaining life. Greater demand for food, water and energy requires better management and use to reduce stress on natural systems and ensure a sustainable future.

Read more in a report by Jonathan Bosch, a first year SSCP PhD student researching transitions to low-carbon energy systems.

Environmental hazards are becoming more frequent and severe, with potentially serious impacts on people, supply chains and infrastructure globally. Advancing our knowledge and understanding of these hazards, and the processes involved, will allow us to better predict, plan for and manage the risks in order to increase resilience to these changes.

Read more in the report by Malcom Graham, a first year SSCP PhD student researching saline intrusion in coastal aquifers.

In addition to natural variability, human activities are causing rapid, large-scale climate and environmental change. Understanding how these processes work as a whole Earth system can improve our understanding of the impacts of these changes and inform responsible management of the environment.

Read more in a report by Rebecca Emerton, a first year SCENARIO PhD student researching approaches to global forecasting of flood risk.

Matthew Bell, Chief Executive at the Committee on Climate Change, concluded the event with a talk on the road to Paris and the issues that could be faced in the climate negotiations.

Read more in a report by Samantha Buzzard, a third year NERC PhD student at Reading investigating the role of surface melt in the retreat and disintegration of Antarctic ice shelves.

Watch videos of all the talks on our YouTube channel.

Find out more about the Science and Solutions for a Changing Planet DTP at Imperial College London.

Find out more about the SCENARIO DTP at the University of Reading and University of Surrey.

This blog post by Jonathan Bosch, an SSCP DTP student, is part of a series on Responding to Environmental Change, an event organised by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) funded Doctoral Training Partnerships at Imperial (SSCP), and the University of Reading and the University of Surrey (SCENARIO).

See the full list of blogs in this series here.

Natural resources are fundamental to human well-being, economic growth, and other areas of human development. Greater demand for food, water and energy resources against the current backdrop of climate change and population growth requires better management and more efficient use of natural resources to reduce the resulting stress on the earth’s natural systems.

In this “benefiting from natural resources” section of the programme there were three talks from representatives of three distinct sectors, presenting how the respective areas of industry, regulatory bodies, and academia are currently dealing with the management of natural resources.

Andy Wales, Director of Sustainable Development at SABMiller plc, made an arresting case for why sustainability is not only important for their business model, but also why it’s vital for its continued success. SABMiller is a multinational beer and soft drinks producing company.

SABMiller presents itself as a local beer brand, although it operates in 40 countries. As such, the business is exposed to the perturbations and vulnerabilities of, principally, local water supplies, but also grain and packaging supply chains. And with 80% of its income coming from developing markets, it cannot secure its future profitability without smart resource management. Procuring primary products from local markets is important to achieving this and therefore water management is critical.

The ‘Prosper’ programme, sits on five sustainable development pillars, and has as its catchphrase, “When business does well, so do local communities, economies and the environment around us. When they prosper, we do.” The five pillars are associated with a “thriving, sociable, resilient, clean and productive world.” Encompassed in these areas is an acknowledgement that not only do water supplies matter, but, for example, ‘clean’ – reducing its carbon footprint, and ‘productive’ – food and land security, are central to ensuring a profitable future.

A number of case studies went some way in demonstrating the achievements of Prosper to date. Already, $40m in efficiency savings have been achieved by programmes implemented in Colombia and India, using a systems approach which helped farmers choose better crop types – reducing water consumption by 30% and raising crop yield by 20%.

In Bogota, India, Prosper highlighted issues of poor land management which caused regular and intolerable spikes in water prices. Water run off was high and productive yield of food crops and milk production was low. A sophisticated approach tackled the problem by simply changing the breed of local milk cows to better benefit from the local ecological conditions. The result was an increase in the milk yield of the region and a sharp reduction in water run-off, securing milk and water availability for all users.

Prosper continues to forge collaborations worldwide in the nexus of water, food and energy security. A partnership with the WWF will continue development in that direction.

Miranda Kavanagh, Executive Director, Evidence Directorate of the Environment Agency, focused her talk on ‘Fracking’, or hydraulic fracturing, which is one of the unconventional techniques of oil and gas extraction currently attracting world-wide media attention for its, as yet, undetermined environmental risks.

The Environment Agency’s role is in delivering on a policy framework set by the relevant government agencies, principally DEFRA. It has three specific roles in achieving this objective: Regulating industries and activities that can potentially harm the environment; advising government, industry and the public about more sustainable approaches to the environment; and specific operational work to protect and improve the environment.

The Environment Agency (EA) is guided by its Evidence Directive, which aims to use evidence to “guide and inspire” their actions and those they advise. It states that they must use the best available evidence, use environmental data to support the decisions of others, and develop a joined up approach to evidence, among other equally impressive visions.

On Fracking, the EA must balance, pragmatically, the needs and interests of different groups concerned with environment, resource exploitation and people, as Kavanagh clarified in the Q&A session. As well as the pure environmental impacts, the EA must consider the effects on people and communities, but also the need for fuel exploitation and energy security; areas of interest of both government and the energy sector.

These needs were highlighted in the Potential Contribution report produced by the UK Institute of Directors, which highlighted the social benefits of one scenario to include a likely decrease in the use of imported gas, 70,000 energy jobs and a net benefit to the Treasury.

These benefits are offset by the environmental risks, which are complex, and in some cases, undetermined. The known risks involve a range of air, land and water pollution, the release of chemical and radioactive substances, and a range of spatial and time dependent risks, which will affect exploited regions differently, and on differing timescales. For example, ground water contamination may take decades to become detectable.

The EA works in many areas to produce evidence for the advice and regulation of future potential fracking operations. The EA was, for example, instrumental in producing a UK geological map of the subsurface extent of shales and their vertical separation to aquifers. These were important as a preliminary risk assessment for a broad geological understanding of the importance and distribution of our groundwater resource. This type of evidence gathering must be done for the range of environmental concerns listed above.

Also highlighted were collaborations and opportunities which the EA are eager to develop. NERC Fellowships and various PhD Studentships are ongoing and include projects as broad as evaluating methodologies for environmental risks, but also the invention and patenting of new instruments for air-quality impacts and other applications.

The EA welcomes partnerships, particularly those involved with their Collaborative Research Priorities. Their expertise and extensive datasets are important resources which other organisations with similar resources and objectives may make use of to aid progress on some key questions within applied environmental science.

Elizabeth Robinson, Professor of Environmental Economics at the University of Reading presented two projects demonstrating her work on how scientists and social scientists can and have been working together to improve our ability to benefit from natural resources.

There has been, in the past, little need to actively manage our natural resource base, but the pressures of climate variability and population growth have made optimising the use of these resources effectively much more important. The relationship between ecosystem services – measurable by ecological scientists – and agricultural intensity – understood by management and social structures – becomes a crucial collaboration.

But what is the relationship between these inextricably connected issues? Robinson was concerned, as a trained economist, with ‘drawing a curve’ between these two dimensions, which would describe how and why a change in the intensity of agriculture would affect the ecosystem services which are critical to the sustainability and well-being of communities.

In Ghana, cocoa production was investigated in order to understand how some farmers may choose to intensify their agriculture and why some do not, and furthermore some intensifications were damaging the ecosystem more than others. Ecologists were employed to determine the relationship between intensity and ecosystem services, while social scientists interviewed farming communities to discover how the forest land was managed and what were the limiting factors to best managing the land in benefiting farmer yield and ecosystems.

It was found that there are often complicated social factors affecting how the farms and forest land was managed, and these included the ability of farmers to use or afford fertiliser, shift cultivation to newly converted forest when soils are exhausted, and even whether farmers benefit from pollination by nearby forests. It was seen that many local perceptions of resource space and property rights restricted the farmers’ ability to optimise their practices even if they desired to do so. Among many other constraints, poverty, labour availability and wages, and institutional contexts affect the outcomes when farmers attempted to intensify their practices.

Ultimately, a simple behavioural model can attempt to capture the ecological boundaries, and social constraints, and can be used to propose routes toward an optimum solution for ecosystem services and farmer preferences and resources.

The second case study was related to managing fisheries in Tanzania, where such efforts are typically addressed only when falling stocks become an issue. This project also highlighted the need to observe the socio-economic situation and implement credible solutions which may indeed lead to a slower recovery of the ecology, but which resolve societal tensions and allow the fishing communities a reliable income without implementing a total fishing ban. A ‘Bio-economic’ model was indispensable in this project too.

Watch a video of the talk on our YouTube channel.

The Climate and Environment at Imperial blog has moved. View this post on our new blog

The Climate and Environment at Imperial blog has moved. View this post on our new blog

by Dr Karl Smith, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering

Every waking hour, I ingest water. Not always in its purest form, but near enough. Energy is important and right now (and rightly so), carbon is capturing headlines. But water is fundamental to our livelihoods.

The UN has designated 22 March World Water Day: “a day to celebrate water”. And why not? Never mind that it’s essential to all life forms. For modern living, it’s a necessity: we need 10 litres of water to make one sheet of paper; 182 litres to make a kilo of plastic. We’re not about to run out of seawater, but what about drinkable freshwater? A glance at the UN’s water statistics reveals the urgency of our situation.

In developing countries, 90% of wastewater flows untreated into water bodies. An estimated 1.8 billion people worldwide drink water contaminated with faeces. By 2030, 47% of the world’s population will be living in areas of high water stress.

In 60% of European cities (population > 100,000 people), groundwater is being used faster than it can be replenished. As the primary source of drinking water worldwide, groundwater is vitally important. In fact, groundwater comprises 97% of all global freshwater potentially available for human use (the UN don’t qualify this definition, but one can probably assume that 97% of all drinking water is groundwater – further enlightenment on this is welcome). Moreover, our use of groundwater is increasing by 1-2% per year.

If we look west to the US then we reach California – a drought stricken state with, according to senior water cycle scientist Jay Famiglietti of the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, only one year of water left in its reservoirs and rapidly disappearing groundwater.

Dwindling water resources are a global challenge. However, at present (again, this is UN data), 54% of the world’s population live in cities. By 2050, this figure will approach 70%, with 93% of urbanisation occurring in developing countries. If you reduce the problem to securing clean water for city dwellers, then it becomes markedly more manageable – at least, if you have big budgets.

London is currently tussling with the proposed Thames Tideway Tunnel (TTT), a £4.2 billion (at 2011 prices) “super sewer” designed to contain overflows of sewage, currently in the order of tens of millions of tonnes a year, and hence prevent the pollution of the river Thames.

Although it will help future-proof the capital against climate change, the TTT won’t do much else than divert sewer overflows: a big spend for one single solution. Moreover, its carbon footprint is not small. A shortcoming of some climate change adaptation interventions is that, through their production and often, operation, they may only amplify the root of the problem.

If we want value for money, then why not demand more than just one benefit? One stone, but at the very least, two birds.

Consider combined heat and power (CHP) plants, which generate two energy types, at improved efficiencies of conversion, from a single fuel. Do we therefore need one pipe network for drinking water, one for waste water and one for stormwater? Plus an array of energy intensive pumps?

Urban floods are invariably caused by runoff from impermeable surfaces – roofs, roads and pavements. A carpet of urban greenery can both trap and, via the plant root network and soil media, decontaminate runoff, removing the need for a centralised stormwater system. The grey city can grow green.

For cities to be self-sufficient and resource-smart, we can’t let stormwater dissipate into drains. Drinking harvested rainwater is problematic, but irrigation of city greenery – not only garden plants but also, fruit and vegetable crops – is not.

Plants are truly multi-functional. Their benefits include enhancements to human health and well-being, as well as mitigating the urban heat island effect and promoting biodiversity. This is the Blue Green Dream paradigm: the smart use of plants, in concert with the local environment and manmade systems such as storage tanks, to sustainably manage water resources and also, deliver myriad urban benefits.

The Blue Green Dream – a multi partner, Climate KIC funded, Imperial College led project – is harnessing ecosystem systems to achieve climate change resilience. For further information, see the project website or contact the project manager, Dr Karl M. Smith.

The Climate and Environment at Imperial blog has moved. View this post on our new blog

by Professor Paolo Vineis and Pauline Scheelbeek, School of Public Health

It is sometimes claimed that addressing climate change with proper policies is too expensive and could lead to a further decline in the economy. However, the co-benefits of implementation of climate change mitigation strategies for the health sector are usually overlooked. The synergy between policies for climate change mitigation in sectors such as energy use (e.g. for heating), agriculture, food production and transportation may have overall benefits that are much greater than the sum of single interventions (Haines et al, 2009). Here we describe a few examples of climate change mitigation strategies that have important co-benefits for global health.

The transportation sector is often the single largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in urban areas. Policy makers have tried to reduce these emissions by discouraging car travel and promoting other means of (active) transport. Active transport, such as cycling and walking, increases daily physical activity. Physical inactivity is one of the leading causes of non-communicable diseases all over the world. It has been estimated that the combination of active travel and lower-emission motor vehicles would give large health benefits, notably from a reduction in the number of years of life lost from coronary heart disease (10-19% in London, 11-25% in Delhi according to Woodcock et al, 2009). Also obesity, which is increasing dramatically all over the world, particularly in children, could effectively be reduced by a more active lifestyle. A 30-minute walk per day could – on many occasions – be enough to even out slight caloric excess.

Improving heating and cooking systems – for example by making them more efficient – reduces energy consumption. Improved models of stoves (electrical vs biomass) allow a 15-times reduction in the emission of particles and other pollutants, thus contributing to decreased emissions in the atmosphere. Especially in developing countries – where old stoves are common – these improvements could also have a considerable positive impact on health: cooking on simple wood or coal stoves currently forms a major source of indoor pollution and increases risk of certain chronic diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The potential effectiveness of this strategy was shown by Wilkinson et al: they calculated that if 150 million low-emission cookstoves were introduced in India, this could lead to the prevention of an estimated 1.3 million deaths from COPD and hundreds of thousands of deaths from other diseases such as coronary heart disease (Wilkinson, et al 2009). Air pollution is one of the biggest environmental causes of death worldwide, with household air pollution accounting for about 3·5-4 million deaths every year (Gordon et al, 2014).

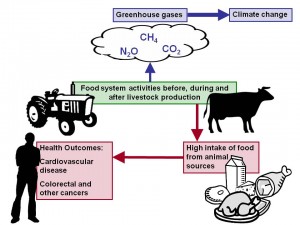

Meat production is highly inefficient energetically: it requires an extremely high use of water and land per unit of meat. One fifth of all greenhouse gases worldwide are related to methane production from livestock farms. Reduction of meat intake by consumers would lower meat production and is therefore often promoted as climate change mitigation strategy. The figure shows that a high intake of meat is also associated with increased disease risk, in particular for certain cancers and cardiovascular disease (WCRF, 2007). Reduced meat consumption would therefore also have a major impact on public health. It has been estimated that a 30% reduction in livestock production in the UK would reduce cardiovascular deaths by 15% (Friel et al, 2009).

Meat production is highly inefficient energetically: it requires an extremely high use of water and land per unit of meat. One fifth of all greenhouse gases worldwide are related to methane production from livestock farms. Reduction of meat intake by consumers would lower meat production and is therefore often promoted as climate change mitigation strategy. The figure shows that a high intake of meat is also associated with increased disease risk, in particular for certain cancers and cardiovascular disease (WCRF, 2007). Reduced meat consumption would therefore also have a major impact on public health. It has been estimated that a 30% reduction in livestock production in the UK would reduce cardiovascular deaths by 15% (Friel et al, 2009).

Non-renewable energy production, for example coal burning, is a major contributor to worldwide greenhouse gas emissions. Many countries have adopted policies to reduce polluting energy production and stimulate production of (renewable) energy through cleaner sources. For example, since 2000, the government in the Chinese Shanxi province has promoted several initiatives (including factory shutdowns) with the goal of reducing coal burning emissions. The annual average particulate matter (PM10) concentrations decreased from 196 μg/m3 in 2001 to 89 μg/m3 in 2010, which – as a matter of fact – is still very high for Western standards. It has been estimated that the DALYs (Disability-Adjusted Life Years) lost in Shanxi had decreased by 56.92% as a consequence of the measures (Tang et al, 2014). The IPCC 5th assessment report stresses that the main health co-benefits from climate change mitigation policies come from substituting polluting sources of energy for renewable and cleaner sources, with a considerable effect on the improvement of air quality.

The co-benefits from climate change mitigation for the health sector have not yet been completely identified and quantified. The topic does not appear on the priority list of political discourse: relevant sectors, including those involved in non-communicable disease prevention (Pearce et al, 2014), transportation, agriculture, food production and climate change (Alleyne et al, 2013), still work separately, while collaboration would improve the synergy between health improvement and climate change mitigation and maximise benefits for both.

References

Alleyne G, Binagwaho A, Haines A, Jahan S, Nugent R, Rojhani A, Stuckler D; Lancet NCD Action Group. Embedding non-communicable diseases in the post-2015 development agenda. Lancet. 2013 Feb 16;381(9866):566-74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61806-6

Friel S, Dangour AD, Garnett T, Lock K, Chalabi Z, Roberts I, Butler A, Butler CD, Waage J, McMichael AJ, Haines A. Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: food and agriculture. Lancet 2009; 374: 2016-25.

Gordon SB, Bruce NG, Grigg J, Hibberd PL, Kurmi OP, Lam KB, Mortimer K, Asante KP, Balakrishnan K, Balmes J, Bar-Zeev N, Bates MN, Breysse PN, Buist S, Chen Z, Havens D, Jack D, Jindal S, Kan H, Mehta S, Moschovis P, Naeher L, Patel A, Perez-Padilla R, Pope D, Rylance J, Semple S, Martin WJ 2nd. Respiratory risks from household air pollution in low and middle income countries. Lancet Respir Med. 2014 Oct;2(10):823-60. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70168-7

Haines A, McMichael AJ, Smith KR, Roberts I, Woodcock J, Markandya A, Armstrong BG, Campbell-Lendrum D, Dangour AD, Davies M, Bruce N, Tonne C, Barrett M, Wilkinson P. Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: overview and implications for policy makers. Lancet. 2009 Dec 19;374(9707):2104-14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61759-1. Epub 2009 Nov 26.

Pearce N, Ebrahim S, McKee M, Lamptey P, Barreto ML, Matheson D, Walls H, Foliaki S, Miranda J, Chimeddamba O, Marcos LG, Haines A, Vineis P. The road to 25×25: how can the five-target strategy reach its goal? Lancet Glob Health. 2014 Mar;2(3):e126-8. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70015-4.

Tang D, Wang C, Nie J, Chen R, Niu Q, Kan H, Chen B, Perera F; Taiyuan CDC. Health benefits of improving air quality in Taiyuan, China. Environ Int. 2014 Dec;73:235-42. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2014.07.016. Epub 2014 Aug 27.

Wilkinson P, Smith KR, Davies M, Adair H, Armstrong BG, Barrett M, Bruce N, Haines A, Hamilton I, Oreszczyn T, Ridley I, Tonne C and Chalabi Z. Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: household energy. 2009. The Lancet, 374: 9705 (P1917 – 29)

World Cancer Research Fund. Recommendations Booklet. Available from: http://www.wcrf.org/

Woodcock J, Edwards P, Tonne C, Armstrong BG, Ashiru O, Banister D, Beevers S, Chalabi Z, Chowdhury Z, Cohen A, Franco OH, Haines A, Hickman R, Lindsay G, Mittal I, Mohan D, Tiwari G, Woodward A, Roberts I. Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: urban land transport. Lancet. 2009 Dec 5;374(9705):1930-43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61714-1. Epub 2009 Nov 26.

By Dr Flora Whitmarsh, Grantham Institute

This blog forms part of a series addressing some of the criticisms often levelled against efforts to mitigate climate change.

The Twentieth Session of the Conference of the Parties (COP 20) – the latest in a series of meetings of the decision making body of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change –began in Lima this week. Many in the media are quick to point to the difficulty of obtaining international agreement on greenhouse gas emissions reductions, and to denounce COP 15, which took place in Copenhagen in 2009, as a failure. Far from being a failure, the Copenhagen meeting paved the way for future climate change action. World leaders agreed ‘that climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our time’ and emphasised their ‘strong political will to urgently combat climate change in accordance with the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities’, and it was agreed that ‘deep cuts in global emissions are required’. The Copenhagen accord also said that a new Copenhagen Green Climate Fund would be established to support developing countries to limit or reduce carbon dioxide emissions and to adapt to the effects of climate change.

The Twentieth Session of the Conference of the Parties (COP 20) – the latest in a series of meetings of the decision making body of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change –began in Lima this week. Many in the media are quick to point to the difficulty of obtaining international agreement on greenhouse gas emissions reductions, and to denounce COP 15, which took place in Copenhagen in 2009, as a failure. Far from being a failure, the Copenhagen meeting paved the way for future climate change action. World leaders agreed ‘that climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our time’ and emphasised their ‘strong political will to urgently combat climate change in accordance with the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities’, and it was agreed that ‘deep cuts in global emissions are required’. The Copenhagen accord also said that a new Copenhagen Green Climate Fund would be established to support developing countries to limit or reduce carbon dioxide emissions and to adapt to the effects of climate change.

The last objective is in progress: the green climate fund was set up at COP 16, held in Cancun, Mexico in 2010, and several major countries have pledged money. Japan has pledged $1.5 billion, the US has pledged $3 billion, Germany and France have pledged $1 billion each, the UK pledged $1.13 billion and Sweden pledged over $500m. This brings us close to the informal target of raising $10 billion by the end of the year. The goal is to increase funding to $100 billion a year by 2020. There have also been several smaller donations. This is a key step in tackling climate change, because the gap between developed and developing countries in their ability to respond to climate change and their level of responsibility for causing the problem must be addressed.

Obtaining international agreement to reduce emissions is a real challenge. It is not surprising that it is difficult to reach consensus on a course of action between a large range of different countries at different stages of development who bear differing levels of responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions to date: the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change has 196 Parties. However, there has been significant progress towards global emissions reductions, led by the EU, China and the US.

Prior to the Copenhagen COP, the UK Climate Change Act was passed in 2008, and contains a legally binding commitment to reduce UK emissions by at least 80% on 1990 levels by 2050. In addition, the UK Committee on Climate Change has recommended an emissions reduction of 50% on 1990 levels by 2025 in order to meet the longer term target. Some have argued that by taking unilateral action, the UK put itself at risk of losing out economically to countries that had not made such pledges. Competitiveness concerns have been evaluated by the Committee on Climate Change, the body set up as part of the Climate Change Act to advise the UK government on emissions targets. The committee found that ‘costs and competitiveness risks associated with measures to reduce direct emissions (i.e. related to burning of fossil fuels) in currently legislated carbon budgets are manageable.’ Continued support from the EU emissions trading scheme may be needed in the 2020s, but this depends on progress towards a global deal.

By making this commitment the UK has been able to enter into negotiations with other countries from a position of strength. The UK is one of the leading historic emitters of carbon dioxide – it is, of course, the sum total of our emissions beginning in the industrial revolution that will, to a good approximation, determine humanity’s impact on the climate, not the emissions in any given year – and therefore it is right that the UK took the lead by making this commitment. Had we not made such a pledge, it would have put us in a more difficult position when negotiating with other countries, particularly those still on the path to development.

The UK is not now acting alone – other major countries have recently made significant emissions reduction pledges. The recent European Council agreement that the EU should cut emissions by 40% on 1990 levels by 2030 represents a step forward. It was decided that all member states should participate, ‘balancing considerations of fairness and solidarity.’ It was also decided that 27% of energy consumed in the EU should be from renewable sources by 2030, and a more interconnected European energy market should be developed to help deal with the intermittency of renewable sources of energy.

The EU target is still not quite as ambitious as the UK target. However, this latest EU agreement is a significant step in the right direction and demonstrates that international cooperation on a large scale is possible, albeit within a body like the EU with pre-existing economic ties. In addition, it generally costs more to cut emissions the faster the cuts are implemented. If the world is genuine in its commitment to tackling climate change, very significant emissions reductions are ultimately required, and delaying action means having to cut emissions more quickly at a later date – at a higher cost. In addition, the Committee on Climate Change found that despite short term increases in electricity prices, early action means that UK electricity prices are projected to be lower in the medium term compared to a fossil fuel intensive pathway, assuming there is an increase in the carbon price in the future.

A recent development is the bilateral agreement between China and the US. China stated that its emissions would peak by 2030, by which time the country aims to get 20% of its energy from non-fossil fuel sources, and the US pledged to reduce its emissions by 26%-28% on 2005 levels by 2025. Some have suggested that the agreement does not go far enough because China’s emissions will continue to rise until 2030 under the deal, and the US target is not as stringent as the EU or UK targets. However, these pledges coming in the lead up to Lima from the two largest emitters globally are hugely significant, and pave the way for further progress. China has already made significant progress in reducing the energy intensity (energy per unit of GDP) of its economy: the 11th Five Year Plan, covering the period 2006-2010 aimed to reduce energy intensity by 20%, and achieved a reduction of 19.1%. Despite some disruption to the energy supply, this success in meeting the target demonstrates the Chinese government’s track record of achieving its objectives on green growth. The current five year plan aims to cut energy intensity and carbon intensity (carbon emissions per unit of GDP) by a further 16% and 17% respectively on 2010 levels by 2015. It is right that developing countries should be able to grow their economies – China’s per capita GDP is still relatively low – and this has to be balanced with climate change targets.

The EU, China and the US together accounted for just over half of total global carbon dioxide emissions in 2013. Their pledges demonstrate that smaller groups of countries made up of the major emitters can make a difference without waiting for far-reaching international agreement on emissions reductions. Their willingness to act also has the potential to spur other industrialised countries into reducing their own emissions. More action is still needed, but there has been significant progress since the Copenhagen conference, which should pave the way for more ambitious pledges.

by Ajay Gambhir, Grantham Institute

This blog forms part of a series addressing some of the criticisms often levelled against efforts to mitigate climate change.

It is often claimed that intermittent renewable sources of electricity (mainly wind and solar photovoltaics), are too expensive, inefficient and unreliable and that we shouldn’t subsidise them.

What are the facts?

What are the facts?

Last year, governments spent about $550 billion of public money on subsidies for fossil fuels, almost twice as much as in 2009 and about five times as much as they spent subsidising renewables (IEA, World Energy Outlook 2014). This despite a G20 pledge in 2009 to “phase out and rationalize over the medium term inefficient fossil fuel subsidies” that “encourage wasteful consumption, reduce our energy security, impede investment in clean energy sources and undermine efforts to deal with the threat of climate change”.

There is a key reason why it makes sense to subsidise the deployment of renewable energy technologies instead of fossil fuels. They are currently more expensive than established fossil fuel sources of power generation such as coal- and gas-fired power stations, because the scale of the industries that produce them is smaller and because further innovations in their manufacture and deployment are in the pipeline. As such there needs to be a period of translating laboratory-stage innovations to the field, as well as learning and scaling-up in their manufacture, all of which should bring significant cost reductions. This is only likely to be possible with either:

Unfortunately, there is unlikely to be a long-term, credible and significant (“long, loud and legal”) carbon price anytime soon, given the immense political lobbying against action to tackle climate change, and the lack of global coordinated emissions reduction actions, which means any region with a higher carbon price than others puts itself at risk of higher energy prices and lost competitiveness. Whilst subsidies are also likely to raise energy prices, their targeting at specific technologies (often under some fiscal control such as the UK’s levy control framework) means they should have less overall impact on prices. In addition, subsidies have helped to put some technologies on the energy map faster than a weak carbon price would have done and have given a voice to new energy industries to counter that of the CO2-intensive incumbents.

Nevertheless, subsidies should not remain in place for long periods of time, or at fiscally unsustainable levels. Unfortunately some countries, such as Spain, have fallen into that trap, with an unexpectedly high deployment of solar in particular leading to a backlash as fiscal costs escalated, rapid subsidy reductions and the stranding of many businesses engaged in developing these technologies. Germany’s subsidy framework for solar, with its longer term rules on “dynamic degression” levels (which reduce over time depending on deployed capacity in previous years) has proven a better example of balancing the incentive to produce and deploy new technologies with the need to manage fiscal resources carefully (Grantham Institute, 2014).

Fortunately, the price of solar and onshore wind has fallen so much (through manufacturing and deployment scale-up and learning that the subsidies were aimed at in the first place) that they are now approaching or have achieved “grid parity” in several regions – i.e. the same cost of generated electricity as from existing fossil fuel electricity sources. Analysis by Germany’s Fraunhofer Institute shows that solar PV, even in its more expensive form on houses’ rooftops, will approach the same level of electricity generation cost as (hard) coal and gas power stations in Germany within the next decade or so, with onshore wind already in the same cost range as these fossil fuel sources. Subsidies should be phased out as the economics of renewables becomes favourable with just a carbon price (which should be set at a level appropriate to reducing emissions in line with internationally agreed action to avoid dangerous levels of climate change).

It’s important to note that grid parity of electricity generation costs does not account for the very different nature of intermittent renewables compared to fossil fuel power stations, which can very quickly respond to electricity demand peaks and troughs and help ensure that electricity is available as required. For example one common contention is that for every unit of solar capacity in northern latitudes, significant back-up of fossil fuel generation (most often gas turbines, which are quick to ramp up) is required to meet dark winter peak demand in the evenings. Indeed, analysis by the US Brookings Institute based on this principle (as given much publicity in The Economist in July 2014) suggested this would make solar PV and wind much more expensive than nuclear, gas and hydro power.

Unfortunately, and as reflected in the published responses to the Economist article, this analysis has proven to be too simplistic: not accounting for the fact that wind and solar provide complementarities since the wind often blows when the sun’s not shining; that electricity grids can span vast distances (with high voltage direct current lines) which effectively utilise wind and sunlight in different regions at different times; that there is a great deal of R&D into making electricity storage much cheaper; that electricity networks are going to become “smarter” which means they can more effectively balance demand and supply variations automatically; and that the costs of these renewable technologies are coming down so fast that (particularly in the case of solar) its economics might soon be favourable even with significant back-up from gas generation.

In summary, the world is changing, electricity systems are not what they once were, and there is a very sound economic case for meeting the challenge of climate change by deploying low-carbon renewable electricity sources. It is encouraging to see that there has been a rapid rise in the deployment of these technologies over the past decade, but more needs to be done to ensure that the low-carbon world is as low-cost as possible. This means supporting and therefore continuing to subsidise these critical technologies to at least some extent.

References

International Energy Agency (2014) World Energy Outlook 2014

Statement from the G20 in Pittsburgh, 2009, available at: https://www.g20.org/sites/default/files/g20_resources/library/Pittsburgh_Declaration.pdf

Grantham Institute, Imperial College London (2014) Solar power for CO2 mitigation, Briefing Paper 11, available at: https://workspace.imperial.ac.uk/climatechange/Public/pdfs/Briefing%20Papers/Solar%20power%20for%20CO2%20mitigation%20-%20Grantham%20BP%2011.pdf

Fraunhofer Institute (2013) Levelized cost of Electricity: Renewable Energy Technologies, available at: http://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/en/publications/veroeffentlichungen-pdf-dateien-en/studien-und-konzeptpapiere/study-levelized-cost-of-electricity-renewable-energies.pdf

The Economist (2014a) Sun, Wind and Drain, Jul 26th 2014, available at: http://www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21608646-wind-and-solar-power-are-even-more-expensive-commonly-thought-sun-wind-and

The Economist (2014b) Letters to the editor, Aug 16th 2014, available at: http://www.economist.com/news/letters/21612125-letters-editor

By Dr Flora Whitmarsh, Grantham Institute

The costs associated with reducing emissions in the UK have been discussed recently in the press. In an article in the Mail on Sunday, David Rose made the claim that energy policies shaped by the so-called “Green Blob” – a term coined by Owen Paterson for what he called “the mutually supportive network of environmental pressure groups, renewable energy companies and some public officials” – will cost the UK up to £400 billion by 2030, and that bills will rise by at least a third.

The costs associated with reducing emissions in the UK have been discussed recently in the press. In an article in the Mail on Sunday, David Rose made the claim that energy policies shaped by the so-called “Green Blob” – a term coined by Owen Paterson for what he called “the mutually supportive network of environmental pressure groups, renewable energy companies and some public officials” – will cost the UK up to £400 billion by 2030, and that bills will rise by at least a third.

How much will action on climate change actually cost? The quoted figure of £400 billion equates to 1-1.5% of cumulative UK GDP over the next sixteen years. The most recent analysis to be carried out by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change suggests that the costs of a low carbon economy would be around 1-4% of GDP globally by 2030. Analysis carried out by the AVOID consortium which includes Grantham Institute researchers found that the costs of staying within 2oC were 0.5-4% of global GDP, and a report on the costs of mitigation co-authored by the Grantham Institute put the costs at around 1% of global GDP. The figure quoted in the Mail on Sunday for the overall costs of decarbonisation is of the order of magnitude projected by experts, but these figures do not take into account the co-benefits of mitigation such as improved air quality and energy security. In fact a recent report by Cambridge Econometrics asserts that the UK’s decarbonisation pathway would lead to a net increase in GDP of 1.1% by 2030, due to structural changes in the economy and job creation resulting from the low-carbon transition.

Whilst these estimates relate to the economy-wide cost of using low-carbon energy rather than carbon-intensive sources such as fossil fuels, it is not immediately clear from them what this means for the cost of living. The rising cost of household energy is a key concern for people in the UK who have already seen significant increases in the average bill since 2004 mainly due to the rising cost of gas. In a report published in 2012, the Climate Change Committee concluded that support for low carbon technologies would add an average of £100 (10%) onto energy bills for a typical household by 2020 – where a typical household is one that uses gas for heating, and electricity for lighting and appliances. A further increase of £25 per household is projected by 2030, but this is less than in a scenario with high levels of investment in gas-fired power generation.

Furthermore, this could be partially offset by improvements in energy efficiency. The Climate Change Committee expects that by 2020 the replacement of old inefficient boilers will reduce bills by around £35 on average. The use of more efficient lights and appliances could reduce bills by a further £85, and improved efficiency in heating, mainly due to insulation, could save another £25 on average. However, making these savings would depend on having the right policies in place to encourage energy efficiency.

By Professor Colin Prentice, AXA Chair in Biosphere and Climate Impacts

Further to previous posts on this blog regarding Owen Paterson’s recent speech to the Global Warming Policy Foundation, I would like to take this opportunity to correct his dismissive statement about biomass energy as a potential contribution to decarbonized energy production in the UK. This is what the former Environment Secretary said:

“Biomass is not zero carbon. It generates more CO2 per unit of energy even than coal. Even DECC admits that importing wood pellets from North America to turn into hugely expensive electricity here makes no sense if only because a good proportion of those pellets are coming from whole trees.

The fact that trees can regrow is of little relevance: they take decades to replace the carbon released in their combustion, and then they are supposed to be cut down again. If you want to fix carbon by planting trees, then plant trees! Don’t cut them down as well. We are spending ten times as much to cut down North American forests as we are to stop the cutting down of tropical forests.

Meanwhile, more than 90 percent of the renewable heat incentive (RHI) funds are going to biomass. That is to say, we are paying people to stop using gas and burn wood instead. Wood produces twice as much carbon dioxide than gas.”

There are two misconceptions here.

(1) It is extremely relevant that ‘trees can regrow’ – this is the whole reason why biomass energy is commonly accounted as being carbon neutral! To be genuinely carbon neutral, of course, every tonne of biomass that is burnt (plus any additional greenhouse gas emissions associated with its production and delivery to the point of use) has to replaced by a tonne of new biomass that is growing somewhere else. This is possible so long as the biomass is obtained from a sustainable rotation system – that is, a system in which the rate of harvest is at least equalled by the rate of regrowth, when averaged over the whole supply region.

Now it has been pointed out several times in the literature (e.g. Searchinger et al., 2009; Haberl et al., 2012) that if biomass is burnt for energy and not replenished (for example, if trees are cut down and the land is then converted to other uses), then it is not carbon neutral. Indeed, the carbon intensity of this form of energy production is at least as high as that of coal. Paterson may have been influenced by a report on this topic (RSPB, Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace, 2012) which drew attention to the “accounting error” by which energy derived from biomass might be classed as carbon neutral while actually being highly polluting. But this refers to an extreme scenario, whereby increased demand for forest products leads to no increase in the area covered by forests. In this scenario, biomass energy demand would have to be met from the existing (global) forest estate, drawing down the carbon stocks of forests and forcing builders to substitute concrete and other materials for wood. This would certainly be undesirable from the point of view of the land carbon balance; and carbon accounting rules should recognize the fact.

Nonethless, this extreme scenario is implausible. It assumes that the value of biomass as fuel would be comparable to that of timber (highly unlikely) and more generally that there would be no supply response to increased demand. In more economically plausible scenarios, the increased demand for biomass fuel is met by an increase in the use of by-products of timber production (which today are commonly left to decay or burnt without producing any energy), and by an increase in the amount of agriculturally marginal land under biomass production – including non-tree energy crops such as Miscanthus, as well as trees.

Paterson’s blanket dismissal of the potential for biomass production to reduce CO2 emissions is therefore not scientifically defensible. Sustainable biomass energy production is entirely possible, already providing (for example) nearly a third of Sweden’s electricity today. It could represent an important contribution to decarbonized energy production in the UK and elsewhere.

(2) It might seem to be common sense that planting trees (and never cutting them down) would bring greater benefits in extracting CO2 from the atmosphere than planting trees for harvest and combustion. All the same, it is wrong. The point is that just planting trees produces no energy, whereas planting trees for biomass energy production provides a substitute for the use of fossil fuels. There is an enormous difference. Indeed, it has been known for a long time that the total reduction in atmospheric CO2 concentration that could be achieved under an absurdly optimistic scenario (converting all the land that people have ever deforested back into forests) would reduce atmospheric CO2 concentration by a trivial amount, relative to projected increases due to burning fossil fuel (House et al., 2002; Mackey et al. 2013).

I thank Jeremy Woods (Imperial College) and Jonathan Scurlock (National Farmers Union) for their helpful advice on this topic, and suggestions to improve the text.

Haberl, H. et al. (2012) Correcting a fundamental error in greenhouse gas accounting related to bioenergy. Energy Policy 45: 18-23.

House, J.I., I.C. Prentice and C. Le Quéré (2002). Maximum impacts of future reforestation or deforestation on atmospheric CO2. Global Change Biology 8: 1047-1052.

Mackey, B. et al. (2013) Untangling the confusion around land carbon science and climate change mitigation policy. Nature Climate Change 3: 552-557.

RSPB, Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace (2012) Dirtier than coal? Why Government plans to subsidise burning trees are bad news for the planet. http://www.rspb.org.uk/Images/biomass_report_tcm9-326672.pdf

Searchinger, T. et al. (2009) Fixing a critical climate accounting error. Science 326: 527-528.

By Dr Simon Buckle, Grantham Institute

Owen Paterson’s remarks on the UK response to climate change miss the point. I do not disagree with him that the UK decarbonisation strategy should be improved. In particular, there is a need for a more effective strategy on energy demand. However, my preferred policy and technology mix would be very different to his and include the acceleration and expansion of the CCS commercial demonstration programme in order to reduce the energy penalty and overall costs of CCS. And without CCS, there is no way responsibly to use the shale gas he wants the UK to produce in the coming decades for electricity generation or in industrial processes, or any other fossil fuels.

Owen Paterson’s remarks on the UK response to climate change miss the point. I do not disagree with him that the UK decarbonisation strategy should be improved. In particular, there is a need for a more effective strategy on energy demand. However, my preferred policy and technology mix would be very different to his and include the acceleration and expansion of the CCS commercial demonstration programme in order to reduce the energy penalty and overall costs of CCS. And without CCS, there is no way responsibly to use the shale gas he wants the UK to produce in the coming decades for electricity generation or in industrial processes, or any other fossil fuels.

However, these are second order issues compared to his call for scrapping the 2050 targets and the suspension of the UK Climate Change Committee. On current trends, by the end of the century, the surface temperature of our planet is as likely as not to have increased by 4°C relative to pre-industrial conditions. The present pause in the rise of the global mean surface temperature does not mean we do not need to be concerned. We are fundamentally changing the climate system, raising the likelihood of severe, pervasive, and irreversible impacts on society and the natural systems on which we all depend.

A cost-effective policy to limit these very real climate risks must be based on concerted, co-ordinated and broad-based mitigation action. This is needed to deliver a substantial and sustained reduction in global greenhouse gas emissions, which continue on a sharply rising trajectory. The best way to create the conditions for such action by all the major emitting economies – developed and developing, in different measure – is through the UN negotiation process, supplemented by bodies such as (but not confined to) the Major Economies Forum. The focus of this process is now on achieving a deal covering emissions beyond 2020, due to be finalised at the Paris summit at the end of next year.

There are encouraging signs of progress, e.g. in both the US and China, and the EU is due to agree its own 2030 targets at the end of this month. But the process is difficult and protracted. I agree with Paterson that 2050 is not the be all and end all. I have argued here that the Paris talks should focus on how the next climate agreement can help us collectively to achieve a global peak in emissions before 2030, the first necessary step to any stringent mitigation target, rather than trying to negotiate a deal covering the whole period to 2050.