New blog address

The Climate and Environment at Imperial blog has moved. Visit our new blog.

The Climate and Environment at Imperial blog has moved. Visit our new blog.

On Saturday, 7th March 2015, I attended the Time to Act climate march. After a winding route through the historic streets of central London, an impromptu sit-down on the Strand, and a spirit-raising day under an early spring sun, we converged on Parliament Square where a number of speakers from charities, trade unions, political parties and other activist groups launched their rallying cries for climate justice, aiming their anger squarely upon the walls of the houses of parliament: the centre of British democracy – those with the power to make change, but who perhaps far too often stand in its way.

For me, it was a particularly sobering experience. Not since my first protest attendance at the million-strong “No War on Iraq” protest of February 2003 had I attended a public protest – it’s still feted as probably the largest protest movement in human history – and I was enthusiastic this time, to show up, hold up my placard, and join thousands of concerned citizens to convey our collective anger at what I see to be the complicit and complacent inaction of our government on the urgent challenges of climate and environmental change, in opposition to the rational, fair minded and compassionate citizenry of the United Kingdom.

However, after the excitement of the day had worn off, I couldn’t help but feel somewhat deflated by the realities of the movement as it exists today, nearly four decades after global warming was raised as an international concern at the World Climate Conference in Geneva in 1979. A decade too, before I was even born.

My main concern was that the attendees, despite coming seemingly from all walks of life, were not justly represented by the big-name speakers in attendance. For sure, there was representation by Greenpeace and Avaaz and many of the usual charitable organisations. There was also representation by a number of trade unions and the equally impassioned orators of environmental-cause NGOs and celebrity activists.

My main concern was that the attendees, despite coming seemingly from all walks of life, were not justly represented by the big-name speakers in attendance. For sure, there was representation by Greenpeace and Avaaz and many of the usual charitable organisations. There was also representation by a number of trade unions and the equally impassioned orators of environmental-cause NGOs and celebrity activists.

But none of the mainstream political parties were present, bar one left-wing Labour MP, John McDonnell. Is climate change an issue undeserving of the legitimacy of our democratic process?

There were however a few refreshingly erudite voices in the form of Bangladeshi campaigner Rumana Hashem, comedian, Francesca Martinez, and the blazing writer and activist – via recorded video message – Naomi Klein, author of This Changes Everything.

Then there was 12 year-old Laurel, who spoke simply on behalf of her generation.

Our climate legacy is to 12 year old Laurel and her generation.

The most invisible group, but those very often with the most to say, were the climate scientists themselves.

There were no scientists in the list of speakers; no scientific media organisations handing out materials; and no science representative block, as there were for many environmental interest groups.

Scientists are absent from the fight. They reliably churn out results, smoothing the climate curves, adding degrees to our predicted future surface temperatures, and adding calamity to the already calamitous ice sheet collapses, and yet we/they stay as staunchly apolitical as ever, perhaps for fear of being discredited as impartial scientists.

But to me, it’s the voice that is most obviously missing from the activist debate. Yes, there are scientists on government panels, and in IPCC working groups, but these are only the places that scientists have a duty to be. It is clear however that any paradigm shifting fight, as demonstrated in the previous century, requires grassroots activism. Not accepting the status quo. It was how civil rights were won in the US, how the suffragettes won women’s rights, and how wars became politically toxic worldwide.

The point often repeated by the many trade union and intellectual activists is that climate change is not only a non-partisan issue, but an issue which many interest groups would gain leverage if they acted together. For example, the occupy movement, anti-capitalist, and others all have a strong mandate to rid the system of austerity politics, rampant capitalism, and the huge projected industrial emissions that go along with it. Likewise scientists are fighting a lonely battle if they insist on fighting from high up in their ivory towers.

The point often repeated by the many trade union and intellectual activists is that climate change is not only a non-partisan issue, but an issue which many interest groups would gain leverage if they acted together. For example, the occupy movement, anti-capitalist, and others all have a strong mandate to rid the system of austerity politics, rampant capitalism, and the huge projected industrial emissions that go along with it. Likewise scientists are fighting a lonely battle if they insist on fighting from high up in their ivory towers.

For the reasons above, and for the very longevity of our own species, I believe that it has become the job of scientists, not only to carry on doing the science that is imperative to human progress, but also to become activists, reporters and educators on this, the main issue of the 21st century.

Grantham Institute Co-Director Professor Joanna Haigh discusses a recent paper which argues that existing climate models ‘run hot’ and overstate the extent of manmade climate change.

It is perplexing that some climate change sceptics, who expend much energy in decrying global circulation (computer) models of the climate, on the basis that they cannot properly represent the entire complexities of the climate system and/or that they contain too many approximations, are now resorting to an extremely simplified model to support their arguments.

It is perplexing that some climate change sceptics, who expend much energy in decrying global circulation (computer) models of the climate, on the basis that they cannot properly represent the entire complexities of the climate system and/or that they contain too many approximations, are now resorting to an extremely simplified model to support their arguments.

The model used in the Sci. Bull. article is a very useful tool for conceptualising the factors which contribute to the relationship between increasing concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and global average temperature – indeed, we use such models as teaching aids for students studying atmospheric physics – but it is in no way fit for purpose as an accurate predictor of climate change. It requires as input the values of a number of parameters and, fundamentally, the choice of these values determines the predicted temperatures

Key here is the “feedback parameter” which represents the knock-on effects of changes in the atmosphere on the initial response to greenhouse gas warming. A positive feedback will make the temperature change larger and a negative one reduce it. For example, as the atmosphere warms it can hold more water vapour which itself is a greenhouse gas, acting to enhance the initial carbon dioxide-induced warming and thus giving a positive feedback. The physics of this process is very well-understood. There are a number of other, both positive and negative, feedback processes but overall, analyses of meteorological observations, modelling and understanding of the physical processes point to a significantly positive value. In the present paper the authors choose a very small value, based on temperatures measured in ice cores over the 810,000 year period of ice ages and inter-glacials. Their analysis is incomplete but anyway not relevant to changes in global climate over decadal-to-century timescales.

Thus by choosing an inappropriate value of the feedback parameter, and also judicious choices of other parameters, the authors end up with their “models run hot” conclusion. Must try harder.

By Dr Flora Whitmarsh, Grantham Institute

The costs associated with reducing emissions in the UK have been discussed recently in the press. In an article in the Mail on Sunday, David Rose made the claim that energy policies shaped by the so-called “Green Blob” – a term coined by Owen Paterson for what he called “the mutually supportive network of environmental pressure groups, renewable energy companies and some public officials” – will cost the UK up to £400 billion by 2030, and that bills will rise by at least a third.

The costs associated with reducing emissions in the UK have been discussed recently in the press. In an article in the Mail on Sunday, David Rose made the claim that energy policies shaped by the so-called “Green Blob” – a term coined by Owen Paterson for what he called “the mutually supportive network of environmental pressure groups, renewable energy companies and some public officials” – will cost the UK up to £400 billion by 2030, and that bills will rise by at least a third.

How much will action on climate change actually cost? The quoted figure of £400 billion equates to 1-1.5% of cumulative UK GDP over the next sixteen years. The most recent analysis to be carried out by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change suggests that the costs of a low carbon economy would be around 1-4% of GDP globally by 2030. Analysis carried out by the AVOID consortium which includes Grantham Institute researchers found that the costs of staying within 2oC were 0.5-4% of global GDP, and a report on the costs of mitigation co-authored by the Grantham Institute put the costs at around 1% of global GDP. The figure quoted in the Mail on Sunday for the overall costs of decarbonisation is of the order of magnitude projected by experts, but these figures do not take into account the co-benefits of mitigation such as improved air quality and energy security. In fact a recent report by Cambridge Econometrics asserts that the UK’s decarbonisation pathway would lead to a net increase in GDP of 1.1% by 2030, due to structural changes in the economy and job creation resulting from the low-carbon transition.

Whilst these estimates relate to the economy-wide cost of using low-carbon energy rather than carbon-intensive sources such as fossil fuels, it is not immediately clear from them what this means for the cost of living. The rising cost of household energy is a key concern for people in the UK who have already seen significant increases in the average bill since 2004 mainly due to the rising cost of gas. In a report published in 2012, the Climate Change Committee concluded that support for low carbon technologies would add an average of £100 (10%) onto energy bills for a typical household by 2020 – where a typical household is one that uses gas for heating, and electricity for lighting and appliances. A further increase of £25 per household is projected by 2030, but this is less than in a scenario with high levels of investment in gas-fired power generation.

Furthermore, this could be partially offset by improvements in energy efficiency. The Climate Change Committee expects that by 2020 the replacement of old inefficient boilers will reduce bills by around £35 on average. The use of more efficient lights and appliances could reduce bills by a further £85, and improved efficiency in heating, mainly due to insulation, could save another £25 on average. However, making these savings would depend on having the right policies in place to encourage energy efficiency.

By Dr Flora Whitmarsh, Grantham Institute

In a lecture to the Global Warming Policy Foundation, the former UK Environment Secretary Owen Paterson has criticised the current government’s climate and energy policies, suggesting there is too much emphasis on renewables and that the consequences of climate change have been exaggerated. A discussion of Mr Paterson’s comments on UK energy policy appears in another Grantham blog by Dr Simon Buckle. Here I will discuss one of the reasons for Paterson’s position, the belief that climate change has been exaggerated.

In a lecture to the Global Warming Policy Foundation, the former UK Environment Secretary Owen Paterson has criticised the current government’s climate and energy policies, suggesting there is too much emphasis on renewables and that the consequences of climate change have been exaggerated. A discussion of Mr Paterson’s comments on UK energy policy appears in another Grantham blog by Dr Simon Buckle. Here I will discuss one of the reasons for Paterson’s position, the belief that climate change has been exaggerated.

Paterson suggested that the Earth has not warmed as much as had been predicted, “ … I also accept the unambiguous failure of the atmosphere to warm anything like as fast as predicted by the vast majority of climate models over the past 35 years, when measured by both satellites and surface thermometers. And indeed the failure of the atmosphere to warm at all over the past 18 years – according to some sources. Many policymakers have still to catch up with the facts.”

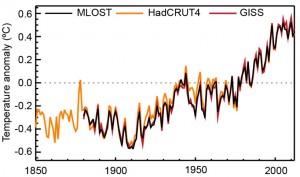

If we look back to earlier attempts to quantify global warming, it is now becoming clear that while these attempts were not perfect, they were not hugely inaccurate either. Natural climate variation is more significant than global warming over shorter time periods, but about 25 years have now passed since the earliest attempts to produce policy-relevant projections of rate of warming, and subsequent publications have started to assess how accurate these projections were.

In late 2013, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a body reporting to the UN, released the first volume of its Fifth Assessment Report. This volume contained an in-depth summary of scientific knowledge about climate science. Scientific understanding of the climate has come a long way since the IPCC released their First Assessment Report in 1990, but the basics of the greenhouse effect were well understood at the time. The projections of future temperature rise in the 1990 report represent the earliest attempt to produce a scientific consensus of opinion regarding the severity of global warming.

A paper published in 2010 by Frame and Stone checked the projections in the First IPCC Report against observed temperature rise. Under the “business as usual” emissions scenario, the IPCC’s best estimate for the projected temperature increase between 1990 and 2010 was 0.55C, within a range of uncertainty. According to two different data sets, temperatures actually increased by 0.35C (HadCRUT3) or 0.39C (GISTEMP) during that period. This is just outside the broader range given by the IPCC, but the IPCC’s range was intended to reflect the uncertainty in the effects of greenhouse gases emissions on the long term warming trend. No attempt was made to include natural climate variability. Frame and Stone performed calculations to account for natural variability using two plausible methods. Both methods showed that the measured temperature increase is consistent with the IPCC’s projections when natural variability is taken into account. In addition, emissions have not been precisely the same as the trajectory used by IPCC, although on this timescale the difference is probably not very significant.

Another early attempt to make policy-relevant projections was published by Hansen et al. in 1988, and results from this work were presented in testimony to the US congress in the same year. Analysis published in 2006 by Hansen et al. demonstrated that the 1988 calculations had been remarkably accurate, with the observed temperatures closely matching those projected under the most realistic emissions scenario. The exceptionally close agreement between the model projections and the observations may have been coincidental since the sensitivity of the climate to carbon dioxide in Hansen’s original model was near the top of the currently accepted range. Nevertheless, the temperature increases projected by the model were close to observations available in 2006.

It is reassuring that these early projections have proved to be of the right magnitude even though the exact rate of warming wasn’t projected. It is worth bearing in mind that the original projections were made about 25 years ago, and the subsequent analysis referenced here was carried out in 2006 and 2010, meaning that only 18-20 years of data is used. This is still not long enough to iron out the full effects of natural variability. Nevertheless, it is now clear that the planet is warming and that humans are responsible, something that could not be concluded unequivocally from the evidence available 25 years ago. It is testament to this overwhelming evidence that those opposed to action on climate change now rely on relatively minor criticisms of climate science to form the basis of their opposition.

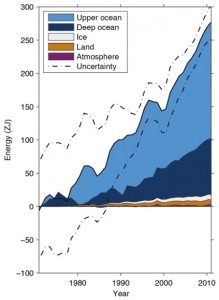

Coming to Paterson’s second point, it is indeed true that there has been no significant increase in global surface temperatures in the 21st century so far. However, global warming is not expected to lead to a linear increase in surface temperatures. Indeed, the First Assessment Report of the IPCC, published in 1990, stated that “The [average global surface temperature] rise will not be steady because of the influence of other factors.” Other factors – notably solar cycles, volcanic eruptions and natural climate variation – are known to affect global surface temperatures. The lack of surface temperature increase this century is due to a combination of factors, but almost certainly there has been some contribution from natural changes in the amount of heat taken up by the ocean. It is important to note that the overall heat content of the planet continues to increase and this is still contributing to sea level rise and ice melt.

Paterson continued, “I also note that the forecast effects of climate change have been consistently and widely exaggerated thus far.

“The stopping of the Gulf Stream, the worsening of hurricanes, the retreat of Antarctic sea ice, the increase of malaria, the claim by UNEP that we would see 50m climate refugees before now – these were all predictions that proved wrong.”

There is a hierarchy of uncertainty in climate change prediction. The increase in surface temperatures at a global level due to the greenhouse effect is well understood scientifically. The total amount of heat in the earth system is increasing due to greenhouse gas emissions, which is having the effect of melting ice and snow and warming the ocean, lower atmosphere and Earth surface. All of these impacts, along with ocean acidification from increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations, are almost certain to continue. Increasing temperatures will also have more complex dynamic effects, including on ocean currents and atmospheric circulation – key aspects of climate variability – as well as on weather patterns, including extreme weather. These impacts are generally harder to predict because there are more factors involved. Putting all of this together and trying to predict the effect of climate change on humans or ecosystems is even more complicated.

The large scale Atlantic Ocean circulation, of which the Gulf Stream forms a part, is driven in part by processes in the North Atlantic that depend on the density of the water in the region. Polar ice melt and changing rainfall patterns due to climate change both have the effect of depositing relatively fresh (and therefore low density) water in the North Atlantic, meaning this process could be affected by climate change. The possibility of a complete shutdown of this North Atlantic circulation has been discussed based on the results of simplified models that show this as a possible outcome. However, mainstream scientific consensus has never been that that this is likely. Again, it is worth going back to older IPCC reports, which form the most comprehensive overview of the scientific understanding of climate change at the time they were written. At the time of the IPCC’s Second Assessment Report in 1995, the available models suggested that the ocean overturning circulation would weaken due to climate change. Subsequent reports in 2001 and 2007 also projected a slowdown and discussed the possibility of a shutdown, but neither report predicted a complete shutdown before 2100. By the time of the latest IPCC report in 2013, the overturning circulation was projected to weaken by between 11% and 34% by 2100. A slowdown has not yet been detected in the observations; this is likely due to the significant natural variability in the strength of the overturning circulation and the limited observational record.

There is more than one way that climate change can affect hurricanes (or tropical cyclones more generally). Heavy rain is almost certainly becoming more frequent and intense globally, and this includes rain that falls during tropical cyclones. In addition there could be an effect on wind speeds or on the frequency of tropical cyclones. The IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report reported observational evidence that the strongest tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic have become more intense and more frequent since the 1970s, although there is no evidence of a global trend.

There has been a global decline in ice and snow due to climate change. Taking sea ice specifically, Arctic and Antarctic Sea Ice have different characteristics. The Arctic sea ice is more long lived and is declining in both area and mass. Antarctic sea ice is not declining in area because the ice is more mobile than in the Arctic meaning its characteristics are more complex. However since its thickness has not been accurately measured, it is not known whether it has gained or lost mass overall. Sea ice is not to be confused with the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets, both of which are losing mass. This is discussed in more detail in a previous blog.

Coming back to the hierarchy of uncertainty, changes in malaria incidence and the numbers of potential climate refugees are in the most uncertain group of impacts. These changes depend on the detailed changes in climate in the location under discussion and the response of humans or mosquitos/malarial parasites to that. A change in malaria incidence is still possible, but this remains the subject of research. As well as local climate conditions, the number of climate change refugees would also depend on the response from local people, governments or other organisations in adapting to the effects of climate change. The number of unknowns here makes it very difficult to predict how many people might be displaced by climate change, but this does not undermine our confidence in climate science itself.

By Professor Joanna Haigh, Co-Director, Grantham Institute

A commentary published in Nature this week has opened up a discussion about the value of using the goal of keeping global warming to below 2°C.

A commentary published in Nature this week has opened up a discussion about the value of using the goal of keeping global warming to below 2°C.

David Victor and Charles Kennel are concerned that the below 2°C target for global warming is not useful, partly because they consider it is no longer achievable and partly because global mean surface temperature does not present a full picture of climate change. The problem comes, of course, in identifying an alternative approach to establishing what is required from attempts to mitigate global warming.

The 2 degree target is in a sense nominal, in that it there is no precise threshold at which everything goes from bearable to unbearable, but it does have the advantage of being easy to understand, for both policy makers and the wider public . The proposed alternative indicators, including ocean heat content and high latitude temperature, have scientific validity but the implications of changes in these parameters may not be obvious to people living away from these areas. Furthermore, monitoring any measure on a real time basis will not avoid the intrinsic variability seen in the global temperature record. Ocean heat content shows an apparently unremitting upward trend at present but a climate change denialist would have been happy to point out a “hiatus” in that trend during the 1960s.

Victor and Kennel also state that “the 2°C target has allowed politicians to pretend that they are organizing for action when, in fact, most have done little”. This criticism would apply to any target – providing it is still at such sufficient distance to remain broadly plausible – and their proposal for “a global goal for average [greenhouse gas] concentrations in 2030 or 2050” would provide equal opportunity for prevarication.

According to a review of recent emissions reduction modelling studies conducted for the AVOID 2 programme co-authored by Ajay Gambhir of the Grantham Institute, it is still possible to meet the 2 degrees C target, provided that a broad portfolio of technologies is available and that there are no significant delays in global coordinated mitigation action. A continuation of relatively weak policies to 2030, or the absence of specific technologies such as carbon capture and storage, could however greatly increase mitigation costs and in some models render the target unachievable.

Nevertheless, Victor and Kennel are right to point out the problems with the current over-simplistic approach and I hope that their initiation of a search for “indicators of planetary health” will spur someone to invent a useful new measure for monitoring and assessing climate change.

Read more about Grantham Institute research on climate mitigation

The Climate and Environment at Imperial blog has moved. View this post on our new blog

By Dr Flora Whitmarsh, Grantham Institute

The recent slowdown in global temperature rise has led to suggestions that global warming has stopped. In fact, the Earth system is still gaining heat, and the slowdown was likely caused by a series of small volcanic eruptions, a downward trend in the solar cycle, and increased heat uptake of the ocean. Writing in the Telegraph, Christopher Booker claims that a new paper by Professor Carl Wunsch (Wunsch, 2014) shows that ocean warming cannot explain the slowdown because the deeper ocean is in fact cooling rather than warming. Booker is incorrect in his interpretation of the paper, as Professor Wunsch explained in a letter of response to the Telegraph editor that was not published. Wunsch also wrote a letter to the editor of The Australian following a similarly misleading article in that newspaper. There are two threads to Christopher Booker’s argument in the Telegraph article. First, he suggests that the new paper refutes the idea that the pause is caused by an increase in ocean heat uptake, an interpretation that is untrue. Second, Booker gives a misleading interpretation of Wunsch’s appearance on the 2007 television documentary The Great Global warming Swindle in which Wunsch’s views were misrepresented by the documentary makers. Below, I describe the significance of ocean heat uptake and then discuss Booker’s two points in turn.

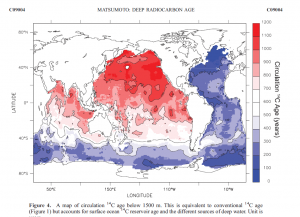

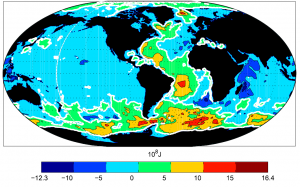

The ocean is an important heat sink and has taken up over 90% of the extra heat absorbed by the Earth system over the last century. There is natural variation in the amount of heat being taken up by the ocean. This is part of the reason why the observed increase in surface temperatures has not been uniform in the past. All studies including this latest one agree that the ocean above 2000 m is absorbing a significant amount of heat and this is the main focus of studies trying to detect and attribute global warming. The study of the ocean below 2000m is interesting from a scientific point of view but is less relevant to the study of climate change because it takes a very long time for heat to mix to these lower layers. Heat is transferred to the deep ocean by the movement of water masses – the mixing driven by the small-scale movement of water molecules is too slow to be of much significance. Due to the locations of the major ocean currents, parts of the deep ocean such as the western Atlantic and the Southern Ocean in the Antarctic have been in contact with the surface relatively recently, meaning they would be expected to have warmed due to global warming. By contrast, much of the Pacific Ocean below 1500 m has not been in contact with the surface for around a thousand years – something that has been demonstrated by studying the radioactive decay of carbon-14 atoms in a technique similar to the carbon dating of objects (Matsumoto, 2007 – see figure 2).

Christopher Booker writes, “Prof Carl Wunsch … has produced a paper suggesting not only that the warmists have no real evidence to support their claim other than computer modelling, but that the deeper levels of the oceans have, if anything, not been warming but cooling recently, thanks to climate changes dating back centuries.”

In the paper under discussion, Bidecadal Thermal Changes in the Abyssal Ocean, Wunsch looks at observations of ocean heat content. He found that the ocean as a whole and the top 700 m had gained heat since 1993, but that there had been an overall decline in heat content below 2000 m according to the available data. There has been a warming in the regions of the deep ocean below 2000 m where it would be expected due to the transport of water from the surface to the abyss by major ocean currents, i.e. the western Atlantic Ocean and the Southern Ocean (see figure 3). There was an observed cooling below 2000 m in other parts of the ocean including most of the Pacific. Much of the deep Pacific Ocean would not be expected to have warmed due to climate change because the water has not been in recent contact with the surface (figure 2). The available observations are very sparse and only about a third of the water below 2000 m was sampled at all during the period under discussion, meaning it is not known whether these results reflect a genuine cooling below 2000 m. Because there was heating in some places and cooling in others, it is particularly hard to accurately determine the mean from very sparse observations. The main conclusion of Wunsch, 2014 was in fact that more observations are needed to improve our understanding of processes involved in transporting water to the deep ocean. This is a subject which has received relatively little attention, with much more research effort being concentrated on the upper ocean. It is likely that this is partially due to the difficulty involved in observing the ocean at depth, and partly because the upper ocean is of interest due to its direct impact on weather patterns, for example through its role in the formation of El Niño and La Niña conditions. None of this changes the fact that the Earth system as whole is gaining heat, and that a significant proportion of that heat is being taken up by the ocean, mostly in the top 700 m. The paper doesn’t significantly change our understanding of the pause in surface temperature rise. We know that natural processes do change the amount of heat taken up by the ocean over time, and that surface temperature rise has not been uniform in the past. However, precisely quantifying how much heat has been taken up by the deep ocean is still not possible with current observations.

Referring to the 2007 television documentary, The Great Global Warming Swindle, Booker suggested that Wunsch had privately held “sceptic” views at the time the programme was aired, but didn’t feel able to express these views in public, “So anxious is the professor not to be seen as a “climate sceptic” that, [after being interviewed for] The Great Global Warming Swindle, he complained to Ofcom that, although he had said all those things he was shown as saying, he hadn’t been told that the programme would be dedicated to explaining the scientific case against global warming.” Professor Wunsch’s views on The Great Global Warming Swindle are explained at length on his professional webpage in an article dated March 2007. I will not paraphrase his comments in detail, but suffice it to say he states his belief that “climate change is real, a major threat, and almost surely has a major human-induced component”, and wrote to the documentary makers to say, “I am the one who was swindled” because they misrepresented his views by quoting him out of context. In an update written three months later, Wunsch made it clear that he did not complain to Ofcom under duress from other scientists. In fact, he felt so strongly that his opinions had been misrepresented that he filed his complaint despite threats by the documentary maker to sue him for libel. References Matsumoto, K. (2007), Radiocarbon-based circulation age of the world oceans, J. Geophys. Res., 112, C09004. Wunsch, 2014: Carl Wunsch and Patrick Heimbach, 2014: Bidecadal Thermal Changes in the Abyssal Ocean. J. Phys. Oceanogr., 44, 2013–2030.

A recent paper on ocean warming has been reported on in a number of newspaper articles, most recently by Christopher Booker in the Sunday Telegraph.

The author of the paper, Professor Carl Wunsch of MIT, wrote a letter to the editor of the Sunday Telegraph in response to Christopher Booker’s article. As the letter has yet to be published in the Sunday Telegraph, with the permission of Professor Wunsch we have decided to post it here.

Dear Editor,

In the Sunday Telegraph of 27 July 2014, Christopher Booker pretends to understand a highly technical paper on ocean warming to such a degree that he can explain it to his lay-audience. Had he made the slightest effort to contact me, I could have told him that the paper in reality says that the ocean is warming overall at a rate consistent with previous values – but that parts of the deepest ocean appear to be cooling. This inference is not a contradiction to overall warming. He imputes to me a wish to hide my views: nothing could be further from the truth. I believe that global warming is an extremely serious threat, but how that threat will play out in detail is scientifically still poorly understood. Anyone who interprets the complexity of change to mean global warming is not occurring and is not worrying, is ignorant enough to regard The Great Global Warming Swindle as a documentary – it is an egregious propaganda piece.

Carl Wunsch

Harvard University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology

by Dr Flora Whitmarsh, Grantham Institute

In an article for the Telegraph, Christopher Booker gave his views on Professor Sir Brian Hoskins’ appearance on the Today programme earlier this year. In the article, Booker made several claims about climate science relating to rainfall, atmospheric humidity, polar sea ice extent, global temperatures and sea level rise. In this blog I will assess his claims against the findings of the latest report of Working Group 1 of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a hugely comprehensive assessment of the scientific literature.

In an article for the Telegraph, Christopher Booker gave his views on Professor Sir Brian Hoskins’ appearance on the Today programme earlier this year. In the article, Booker made several claims about climate science relating to rainfall, atmospheric humidity, polar sea ice extent, global temperatures and sea level rise. In this blog I will assess his claims against the findings of the latest report of Working Group 1 of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a hugely comprehensive assessment of the scientific literature.

Booker’s comment: “Not even the latest technical report from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) could find any evidence that rainfall and floods were increasing.”

Scientific Evidence:

The IPCC report found a significant climate influence on global scale changes in precipitation patterns (with medium confidence), including increases in precipitation in northern hemisphere mid to high latitudes. Further evidence of this comes from the observed changes in sea level salinity, an indication of the global distribution of evaporation and precipitation. The data is currently too inconclusive to report other regional changes in rainfall with confidence. Overall, however, there had been little change in land-based precipitation since 1900, contrasting with their 2007 assessment, which reported that global precipitation averaged over land areas had increased.

The IPCC concluded that there continues to be a lack of evidence and thus low confidence regarding the sign of trend in the magnitude and/or frequency of floods on a global scale.

The IPCC’s projected short-term changes (2016-35) in rainfall were:

There is also likely to be an increase in the frequency and intensity of heavy precipitation events over land. Regional changes will be strongly affected by natural variability and will also depend on future aerosol level (emissions and volcanic) and land use change.

Global rainfall totals are expected to go up in the longer term (i.e. beyond 2035) by around 1-3% per degree Celsius of global mean surface temperature increase, except in the very lowest emissions scenario.

Booker is partially right on past changes: the IPCC found no significant trend in global average rainfall over land. But this is not to say there has been no effect. Indeed, the expected increase in extreme heavy rain is already happening: the IPCC concluded with medium confidence that since 1951 there has been an increase in the number of heavy precipitation events in more regions than have had a decrease.

Read more about the impacts of climate change on UK weather

Booker’s comment: “From the official National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) satellite data on humidity (shown on the “atmosphere page” of the science blog Watts Up With That), we see it has actually been falling.”

Scientific Evidence:

The key measure of whether atmospheric humidity is rising or falling is specific humidity, i.e. the mass of water vapour in a unit mass of moist air. The “atmosphere page” of “Watts Up With That” when accessed on 17 July wrongly shows data on relative humidity under the heading “Specific humidity”. Relative humidity is a measure that depends on temperature and does not therefore measure the absolute water vapour content of the atmosphere. In other words, Booker’s evidence is not evidence.

The latest IPCC report concludes that it is very likely that global near surface and tropospheric air specific humidity have increased since the 1970s. However, during recent years the near-surface moistening trend over land has abated (medium confidence). The magnitude of the observed global change in water vapour of about 3.5% in the past 40 years is consistent with the observed temperature change of about 0.5°C during the same period. The water vapour change can be attributed to human influence with medium confidence.

Booker’s comment: “As for polar ice, put the Arctic and the Antarctic together and there has lately been more sea ice than at any time since records began (see the Cryosphere Today website).”

Scientific Evidence:

The IPCC found that since 1979, annual Arctic sea ice extent has declined by 0.45-0.51 million km2 per decade and annual Antarctic sea ice extent has increased by 0.13-0.20 million km2 per decade. Taking the two IPCC estimates together, it can be inferred that total global sea ice extent has declined since 1979.

Sea ice thickness is harder to measure. The IPCC combined submarine-based measurements with satellite altimetry, concluding that Arctic sea ice has thinned by 1.3 – 2.3 m between 1980 and 2008. There is insufficient data to estimate any change in Antarctic sea ice thickness.

The reason why the Arctic sea ice has declined and the Antarctic sea ice hasn’t is because they have very different characteristics. Arctic sea ice is constrained by the North American and Eurasian landmasses to the south. In the central Arctic Ocean, the ice can survive several years, which allows it to thicken to several meters. Due to climate warming, the Arctic summer minimum has declined by around 11.5% per decade since 1979, and the extent of the ice that has survived more than two summers has declined by around 13.5% per decade over the same period. This has serious consequences for the surface albedo (reflectance) of the Arctic, as a reduction in the highly reflecting sea ice with less reflective open water results in enhanced absorption of solar radiation.

In contrast to the Arctic, Antarctic sea ice forms in the open ocean with no northern land to constrain its formation. The vast majority of Antarctic sea ice melts each summer.

Booker mentioned sea ice specifically, but he did not mention the other important components of the global cryosphere. Making use of better observations than were available at the time of their previous report in 2007, the IPCC carried out an assessment of all the ice on the planet and concluded that there had been a continued decline in the total amount of ice on the planet. The Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets are both losing mass (with very high confidence and high confidence respectively). Glaciers are known to be declining globally (with very high confidence). Overall snow cover, freshwater ice and frozen ground (permafrost) are also declining, although the available data is mostly for the Northern hemisphere.

Booker says: “As for Sir Brian’s claim that by 2100 temperatures will have risen by a further ‘3-5oC’, not even the IPCC dares predict anything so scary.”

Scientific evidence:

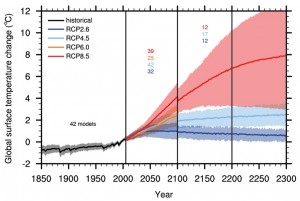

Future temperature rise of course depends on greenhouse gas emissions. In the lowest of the IPCC emissions scenarios, which assumes that global carbon dioxide emissions will decline after 2020, reach zero around 2080, and then continue dropping to just below zero by 2090, temperatures are projected to increase by another 0.3oC – 1.7oC by 2100. Total warming under this scenario is projected to be 0.9oC – 2.3oC relative to 1850-1900, i.e. including warming over the 20th century. Under the highest emissions scenario, the closest to business as usual, another 2.6oC – 4.8oC of warming is projected by 2100. In this case, the total projected temperature rise by 2100 is 3.2oC – 5.4oC when past temperature rise is included.

It is worth emphasising that if emissions are not constrained then we are likely to see a temperature rise of the same order as the projections under the IPCC’s highest emissions scenario. All three of the other scenarios assume that carbon dioxide emissions will peak and then decline substantially at some point in the coming decades. If emissions continue to rise then we should expect a total temperature increase in the region of 3.2oC – 5.4oC by the end of the century. This can of course be avoided if action is taken to reduce fossil fuel dependency.

Booker says: “[Professor Hoskins] was never more wobbly than when trying to explain away why there has now been no rise in average global temperatures for 17 years, making nonsense of all those earlier IPCC computer projections that temperatures should by now be rising at 0.3C every decade.”

Scientific evidence:

Climate change is a long term trend, and a few decades worth of data are needed to separate the warming trend from natural variability. Global mean surface temperature increased by about 0.85oC over the period 1880-2012. Each of the last three decades has been warmer than all previous decades in the instrumental record and the decade of the 2000s has been the warmest.

The observed temperature record over the 20th Century shows periods of slower and faster warming in response to a number of factors, most notably natural variability in the climate system, the changes in atmospheric composition due to large-scale human emissions of greenhouse gases and aerosols from burning fossil fuels and land-use change, volcanic activity and small changes in the level of solar activity.

In future, there will continue to be natural variation in temperature as well as a long term warming trend due to our greenhouse gas emissions. Significant natural climate variability means that a prolonged continuation of the current slowdown in the rate of increase would not on its own be strong evidence against climate change, provided that: 1) the global mean sea level continued to rise due to thermal expansion of the oceans, the melting of glaciers and loss of ice from ice sheets, and 2) the measured net energy flow into the climate system (predominantly the ocean) remained significantly positive.

The climate models used by the IPCC are not designed to predict the exact temperature of the Earth surface in a particular year or decade. This would require scientists to predict the future state of climatic phenomena such as the El Niño Southern Oscillation or the Pacific Decadal Oscillation for a specific period several years in advance, something that is not currently possible. Volcanic eruptions also have an impact on global temperatures, and they are not known about far enough in advance to be incorporated into the IPCC’s model projections.

Read more in our Grantham Note on the slowdown in global mean surface temperature rise

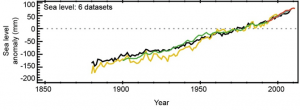

Booker says: “NOAA’s data show that the modest 200-year-long rise in sea levels has slowed to such an extent that, if its recent trend continues, by the end of the century the sea will have risen by less than seven inches.”

Scientific evidence:

The IPCC assessed the relevant data carefully and concluded that sea level rose by around 19 cm (about 7 ½ inches) between 1901 and 2010. This is based on tide gauge data, with satellite data included after 1993. The rate of sea level rise was around 3.2 mm (about 1/8th inch) per year between 1993 and 2010. This is faster than the overall rate since 1901, indicating that sea level rise is accelerating as would be expected from thermal expansion of seawater and increased melting of ice on land.

Future sea level projections under the highest IPCC emissions scenario tell us what is likely to happen if emissions continue to rise unabated. In this case, sea level is projected to increase by a further 63 cm (about 24 ¾ inches) in the last two decades of this century compared with the 1986-2005 average. Even in the lowest emissions scenario, which requires substantial emissions reductions, another 40 cm (about 15 ¾ inches) of sea level rise can be expected by 2100.

Read more in our Grantham Note on sea level rise.

Reference for figures:

IPCC, 2013: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Stocker, T.F., D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex and P.M. Midgley (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 1535 pp.

By Dr Flora Whitmarsh, Grantham Institute

Last week I attended Weather Fronts, an event organised by Tipping Point. The event brought climate scientists together with writers of fiction and poetry to discuss how authors can bring climate change into their work.

Climate change is a global problem and solving it requires collective action. When too many citizens fail to exercise their voice, it is harder for such problems to be adequately addressed at the societal level. Artists have a voice they can use to communicate about the things that concern them. Writing about global warming of course has the potential to raise awareness of its impacts and possible solutions. Novels or poems can be more engaging for some audiences than scientific documents or news reports.

After two thought-provoking keynote speeches from John Ashton and Professor Chris Rapley, and a writer’s panel with Maggie Gee, Jay Griffiths, Gregory Norminton, and Ruth Padel, much of the time was spent in small group discussions. We talked about diverse subjects including utopia and dystopia in fiction, uncertainty in climate modelling, and who should take decisions about climate change. I met novelists, graphic novelists and poets who were passionate about the environment, many of whom are already writing about the subject.

Literature would seem to be the perfect medium to bring climate change to life, but the muse is fickle and anybody setting out to write fiction with an explicit message could struggle to create engaging art. The danger is in creating something more akin to propaganda: a story with an obvious message, and unrealistic or one dimensional characters who function as little more than a mouthpiece for the author’s own opinions.

We often hear that the best way to write about climate change is to create a “positive vision of the future”, something that probably works well in science communication and outreach. But in art this can be less effective, because one runs the risk of the message being too obvious.

It is often said of climate change communication that we should avoid overly frightening or guilt-inducing messages, because this risks evoking fear and powerlessness. At the conference one writer suggested that dystopias are easier to write than utopias, suggesting it could be difficult to create art with a positive message about the future. However, a future in which climate change has been solved need not be a utopia. One solution to all of this is to write a futuristic story about something else entirely, but set it in a world powered by renewable energy without explicitly alluding to climate science or policy.

The conflict between creating good art and giving it some sort of message cannot be easily solved, but one experienced writer summed up the answer in the words of Emily Dickinson: “Tell all the truth, but tell it slant”. In other words, in fiction it can often be more effective to hint at your message or arrive at it in a roundabout way than to spell it out explicitly.

BBC’s Question Time on 14 November saw Lord Lawson citing the IPCC findings to support one of his arguments. Did I dream that? Then I realised that, of course, the reference to the IPCC was incomplete and misleading so I knew I was awake and back in the strange media-distorted world of the UK debate on climate change.

According to the Daily Express, Lord Lawson said that “If you look at the inter-governmental panel on climate change they say there is absolutely no connection between climate change and tropical storms.” Wrong, but convenient for someone who argues we probably don’t need to do anything much about climate change.

What the IPCC actually said in the admirably cautious Technical Summary of the Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) was that:

“Globally, there is low confidence in attribution of changes in tropical cyclone activity to human influence. This is due to insufficient observational evidence, lack of physical understanding of the links between anthropogenic drivers of climate and tropical cyclone activity, and the low level of agreement between studies as to the relative importance of internal variability, and anthropogenic and natural forcings.”

So far so good for Lord Lawson, but then, the IPCC goes on to say:

“Projections for the 21st century indicate that it is likely that the global frequency of tropical cyclones will either decrease or remain essentially unchanged, concurrent with a likely increase in both global mean tropical cyclone maximum wind speed and rain rates (Figure TS.26). The influence of future climate change on tropical cyclones is likely to vary by region, but there is low confidence in region-specific projections. The frequency of the most intense storms will more likely than not increase substantially in some basins. More extreme precipitation near the centers of tropical cyclones making landfall are likely in North and Central America, East Africa, West, East, South and Southeast Asia as well as in Australia and many Pacific islands.” (my emphasis).

In making this statement, the IPCC reflects the fact that, while the science is by no means settled, there are a number of studies that provide physical mechanisms linked to climate change that suggest the frequency of the most intense storms would increase with warming. As I understand it, the warmth of the near surface ocean provides the basic fuel for the cyclone: the winds spiralling around the system evaporate water which cools the ocean and puts latent heat into the atmosphere. When the air rises and the water condenses in deep convection in the storm the heating leads to extra ascent, drawing in more air and leading to faster surface winds. The warmer the ocean is, the more fuel there is for a potential tropical cyclone, and the stronger they could be. Many other aspects come into play such as the changing winds with height and the temperature of the atmosphere up to 15 km. However, in a warmer world, the potential for stronger storms is there.

Indeed, based on this sort of evidence, the quote highlighted above is a statement that the IPCC judges there is more than a 50% chance that the frequency of the most intense storms will increase substantially in some ocean basins. So if Typhoon Haiyan was not affected by climate change and yet was still one of the most powerful storms ever making landfall, it’s clear that the Philippines and other regions exposed to tropical cyclones have a lot to worry about unless we make a “substantial and sustained reductions of greenhouse gas emissions (SPM Section E).” It would be good to see Lord Lawson quoting that particular part of the IPCC AR5 report!