What a strange, circuitous, six-decade trip that must have been! I recently spent some time in the BBC’s archives tracking down the script of a radio programme about the effect of industrial automation on employment – the topic of my research for Nesta – and I was struck by the long journey the script had to go through before it could become a word document on my laptop.

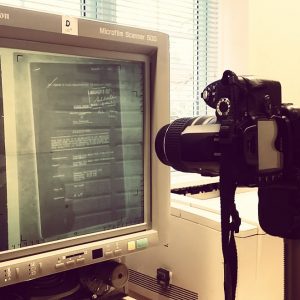

In this age of instant access to information and the [Ctrl + F] search function ([Command + F] for you mac people), it can be easy to forget that tracking down information was not always this easy. Which is why my time in the BBC archives left such an impression on me. For the aforementioned script to make it all the way from 1956 to my computer in the year 2016, the data went through a dozen different forms: What started out as a handwritten script became a type-written script; became a carbon copy of a type-written script; became a photograph of a carbon copy; became a microfilm image of a photograph. The microfilm then sat in various filing cabinets for sixty years until, at last, in August 2016 it became a projection of a microfilm image onto the screen of a microfilm reader; became a photograph of the screen of a microfilm reader; became a photograph on the memory stick of a DSLR; became a JPG on my computer; became a PDF; became a simple text analysis by an Optical Character Recognition programme; and, finally, became a word file on my computer. Considering the iterations the script went through on its way to my computer, it is hard to believe that the OCR was able to recognise anything!

I also find it hard to believe that so much of the BBC’s historical records exist in forms of memory such as this – especially considering that microfilm has long since surrendered the mantle of ‘Best Way to Store Data’. According to one of the archivists who helped me operate the microfilm readers, few companies manufacture parts for the clunky, aged machines, so there is little the archivists can do when one breaks down. Even worse, the machines are also starting to damage the microfilms themselves. As I was sitting at the microfilm reader I came across a two-page section that I really liked. When I rewound the film to read the passage again, however, I found that the microfilm reader had left a gouge on the film itself.

I also find it hard to believe that so much of the BBC’s historical records exist in forms of memory such as this – especially considering that microfilm has long since surrendered the mantle of ‘Best Way to Store Data’. According to one of the archivists who helped me operate the microfilm readers, few companies manufacture parts for the clunky, aged machines, so there is little the archivists can do when one breaks down. Even worse, the machines are also starting to damage the microfilms themselves. As I was sitting at the microfilm reader I came across a two-page section that I really liked. When I rewound the film to read the passage again, however, I found that the microfilm reader had left a gouge on the film itself.  The words that had waited six decades to be rediscovered – and had existed only seconds before – were now lost to history. It was a sad moment.

The words that had waited six decades to be rediscovered – and had existed only seconds before – were now lost to history. It was a sad moment.

One can only hope the BBC sees fit to digitise its archives before more information is lost. Perhaps they could even build a machine that would automate the process. Though, were that to happen, I suppose I might be out of a job.